Edinburgh Book Festival reviews: Katja Hoyer | Jenny Erpenpeck | Linton Kwesi Johnson | Polly Toynbee + more

I’ll start off the weekend round-up with Katja Hoyer, not somebody I’d ever heard of before, talking about something I’d never thought about either. But that’s what book festivals do: they open your mind, widen it and introduce you to new people.

If you were in the Baillie Gifford (yes, let’s hear it for the festival’s excellent sponsors) West Court at the Edinburgh College of Art at 4pm on Saturday, you’d have heard Hoyer talking about being four years old on 7 October, 1989. East Germany, where she lived, was then – just like the Book Festival now – 40 years old, but unlike the Book Festival, was celebrating with a military parade.

Her parents took her to the TV tower in Berlin’s Alexanderplatz, the city’s highest landmark, and they went 200m up in the lift to the revolving bar. She headed straight to the windows to look down on the city spread out below them, her dad went to get the drinks.

Now, you know what’s going to happen and I know what’s going to happen, but Katja was just a four-year-old kid. So when she sees miniaturised crowds and miniaturised military police vehicles rushing in to meet them, it’s all quite exciting. Her father, who might well have heard about what happened six months earlier in Tiananmen Square, Beijing isn’t excited at all. “He went white as a sheet, and got us all down in the lift and out of Berlin in our Trabant.”

Although this demonstration was pivotal, the fall of the Berlin Wall wouldn’t happen for another month. But what made Hoyer’s account stick in my mind was something else she said: “Until then, I’d always assumed that my parents knew what was happening, and now I realised that they didn’t. Things were changing and they didn’t know how.”

Hoyer, now a historian shared the stage with the renowned novelist Jenny Erpenpeck, who was 23 when the Wall came down at the end of her street.

For her family, though, this caused mixed feelings, for her grandfather Fritz was one of a tiny group of communist Germans brought back by Walter Ubricht from exile in Stalin’s Russia to set up the new country of East Germany. And this was the bit I had never thought about: just exactly how did a truckload of communists set up and rule a country steeped in fascism?

The session was chaired by outgoing Book Festival director Nick Barley with his customary intelligence, and Hoyer’s story about change seemed to echo throughout the weekend.

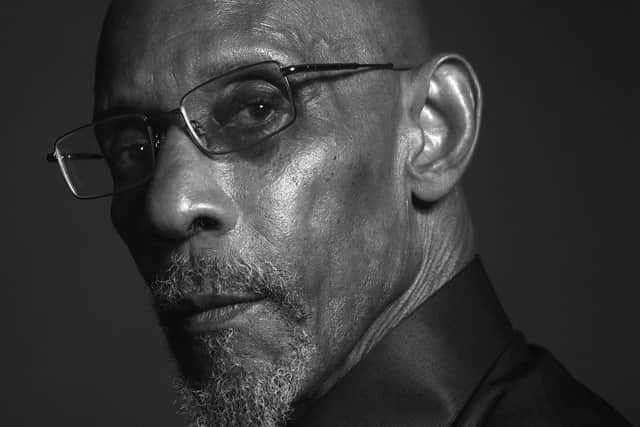

Take Linton Kwesi Johnson. He has been to the festival before, in that heatwave August of 2019, but somehow I missed him. The first 40 minutes, of what started off as a rather dull event, in which he talked about the political roots of his poetry, put some factual flesh on my ignorance of dub poetry but no emotion – perhaps inevitable, as he was talking about a book of his collected prose.

Then he read a beautiful poem about the last time he saw his mother, and the event was transformed. This was what his audience wanted: a taste of the poetry, not the prose; it has made him one of only three people to get the Penguin Modern Classics treatment while still alive. At the end, he was asked about change. For people of Caribbean descent, was it still true that, in the words of his 2007 poem, Inglan is a Bitch?

“We’ve changed Britain,” he said. “Through autonomous institutions, through demonstrating, through riots, uprisings and insurrections, we were able to break down the barriers to racial integration. We’ve changed Britain. And inevitably, we’ve changed ourselves. We’ve become more British. We’re no longer on the periphery of British society. We’re a little bit closer to the centre.”

For Polly Toynbee, Britain isn’t changing enough: the social mobility of the 1970s has gone into reverse and “birth is destiny more than it even was in my childhood”. At least back then, she said, Tories used to give a damn about the lower orders with whom they’d fought the war, and Harold Macmillan built 350,000 council houses. But Margaret Thatcher ruined the country with the “failed experiments of privatising water, trains and electricity” and George Osborne “took £37 billion off the poor – not those with the broadest shoulders”.

Taxes might go up, she said, but they’ve been lower than in Germany, Scandinavia and France for so long it has compounded the collapse of our infrastructure (“imagine, no pot-holed roads, no falling-down hospitals and schools”).

And although the event – which attracted this year’s biggest online festival audience so far – was ostensibly about her own ultra-privileged family of historians, philosophers and professors (“with, sadly, not a working-class person in sight”), she was electrifyingly eloquent about the wider picture.

The middle classes, Toynbee said, need to tell politicians they shouldn’t be petrified of raising taxes. “Mrs Thatcher used to say, ‘You will always spend the pound in your pocket better than the state will’. I say the opposite is true. Everything we most care about – security and safety, your family’s health and education, beautiful public buildings, surroundings and parks, a decent law-abiding society that works, not having children who can’t afford a breakfast before they go to school or a lunch. Those things are far more valuable than anything you buy in a shop.”

So much for big-picture political change. But there were plenty of examples of changes in individual writers’ lives too.

For Alice Oseman, on the children’s programme, it must have been the moment she pitched her queer teen drama Heartstopper to Netflix (adding screenwriter and executive producer to her writer and illustrator jobs) so successfully that this month we’re already on Season 3. She’s still only 28.

For comedian and debut novelist Sarah Pascoe, it might have been the moment she got off the £12 return overnight bus from London for her first Edinburgh with Shakespeare For Breakfast (still going, minus Pascoe, still at C Venue 32 years later) and walked into the most beautiful city she’d ever seen.

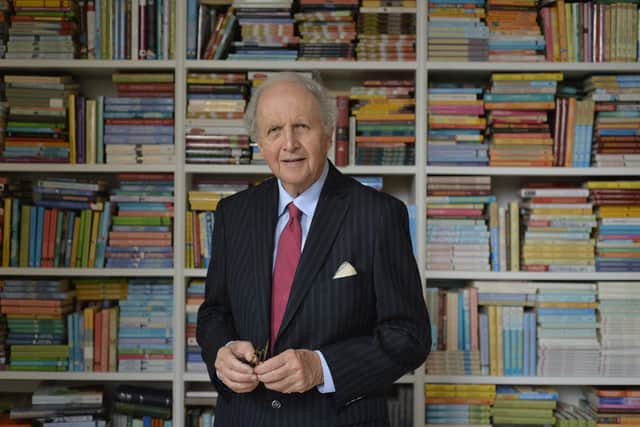

For Alexander McCall Smith, it might have been when, expecting a quick get-to-know-you coffee with his New York publisher of his No1 Ladies’ Detective Agency novels, he found himself being treated to a three-hour lunch with so many of the publisher’s staff that they’d hired the whole restaurant.

“At four o’clock, when I left, I realised that life was going to be rather different for me. I was passing a shoe shop that had in the window what they said were ‘Genuine Elk Shoes’. So I thought, ‘Why not?’ It turns out, though, that they didn’t last long. Elk skin is very good – when it’s on the elk. Not so much for shoes.”

He has, he said, recently been seriously ill after being bitten by a tick in Canada and was treated in the infectious diseases ward in Edinburgh’s Western General Hospital. The staff are brilliant, everyone gets a private room, and people tend to stay away from you. I had a very good time – when I was conscious.”

Clearly recovered, he was in excellent form, and is planning to write a new series, The Perfect Passion, which will be set in a dating agency. Next month sees the publication of both From A Far and Lovely Country, the 24th book in his Mma Ramotswe series, and in this newspaper starting on 4 September, the 17th volume of 44 Scotland Street, now easily the longest-running serial novel in the world and one which, in October, will even have (written by Anna Marshall) its own cookbook.