Art reviews: Instant Whip: The Textiles and Papers of Fraser Taylor 1977-87 Revisited | France-Lise McGurn: What Everyone Wants | Alexander Moffat at 80

Instant Whip: The Textiles and Papers of Fraser Taylor 1977-87 Revisited, Reid Gallery, Glasgow School of Art ****

France-Lise McGurn: What Everyone Wants, Modern Institute, Glasgow ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAlexander Moffat at 80, Fire Station Creative, Dunfermline ****

What does it mean to open a box and find the archive of your younger self? This is what happened to designer Fraser Taylor in 2014 when he discovered material he had assumed was long lost: the work he made as a student of Printed Textiles at Glasgow School of Art between 1977 and 1981, work made subsequently at the RCA, and work from the four years he spent with legendary fashion and design collaborators The Cloth.

He donated the archive to GSA where it was damaged in the first fire. Now restored, it is presented here alongside new work he has made in response.

Co-curated by Panel and GSA’s Dr Helena Britt, the show is elegantly staged and easy to navigate. Sketchbook pages and prototype designs show Taylor’s visual language evolving; a GSA student trip to the Highland village of Morvich was a key moment, when he began to work with silhouettes and shadows, abstracted figures against landscape.

Photographs and ephemera celebrate a vibrant period when the Printed Textiles Department, headed by Jimmy Cosgrove, was sizzling with collaborations and initiatives, art, music and fashion (not to mention some splendid haircuts), and everyone was interdisciplinary before the word was properly in vogue. Instant Whip is the title of a Scottish style mag of the time, this also being the golden age of style mags.

The energy continued at the RCA where Taylor went next, along with his GSA collaborator David Band, and the two formed The Cloth along with Brian Bolger and Helen Manning. Their lines of clothing and designs, which were adapted to feature on everything from hairdressing products to the walls of Glasgow’s SubClub, seemed to encapsulate the mid 1980s moment: big, bold, bright, gestural.

Advertisement

Hide AdTaylor, who now has a multidisciplinary practice as an artist, an honorary professorship at GSA and a role as guest curator at the Beacon in Greenock, presents new work from his Haxton label (founded 2020) inspired by the rediscovery of those early pieces.

So the show is about then and now, and presents both beautifully, but there is a perplexing gap in the middle. What is missing is any context for the viewer who arrives without a knowledge of Taylor’s long career. There are no clues as to what happened between the disbanding of The Cloth and the founding of Haxton which might help us know this man better, and understand more about why his work is important.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhen Taylor went to RCA, he was promptly packed off to the British Museum to work on his drawing. A striking work survives from this period, free-flowing figures (presumably classical statuary) captured in clean, confident lines. And one can draw a clean, confident line across Glasgow from GSA to France-Lise McGurn’s exhibition at Modern Institute’s Airds Lane space, for she is a master of capturing the figure in the same way.

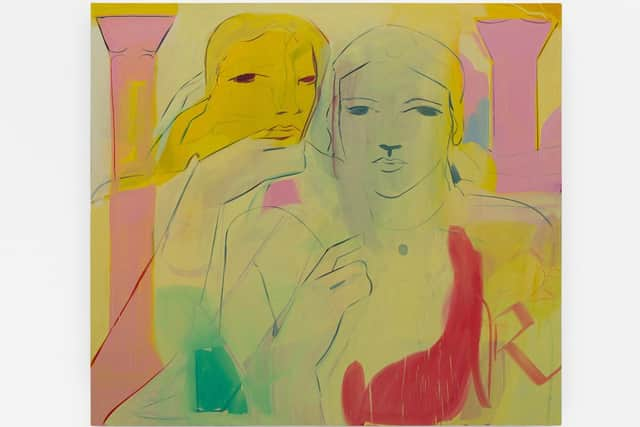

Entering the gallery, one finds oneself in the midst of a crowd. McGurn’s figures are everywhere, lounging languidly on the walls, smoking, gesturing, dancing, smooching on the stairs. Figures on canvas are layered on top of figures painted directly onto the walls, which are also layered with smudges and splashes of colour. It feels improvised and dynamic, as if one is witnessing the aftermath of a performance.

There is a 1980s vibe here, too: a colour palette of pinks and yellows, dashes of fluorescence. McGurn draws on retro pop culture references from film and TV, advertising, window displays. The title is a nod to the now defunct line of shops, founded in Glasgow and doing budget fashion long before it became ubiquitous. Yet, the figures themselves are timeless, usually nude, oozing glamour, as elegant as art deco goddesses – or Greek ones.

While the spontaneity of the work won’t be to everyone’s tastes, the energy of it is unmistakable. McGurn adds plump cherub-like babies, smiley-faced flowers, almost like doodles. Some of the canvases have notes in the margins; one has a scribbled phone number. It feels ephemeral. It’s hard to assess what power a single canvas will have when it is taken away from the vibrating energy of the whole. But, for the moment, however brief that moment is, what energy, what life.

The intention in McGurn’s work might be the opposite to a portrait, which is about capturing the essence of a subject and laying it down for posterity. This has been the driving aim of the work of Alexander (Sandy) Moffat, who celebrates his 80th birthday with a show at Fire Station Creative in Dunfermline, the town in which he was born.

Moffat, who influenced a generation of artists as head of drawing and painting at GSA, has a specific sense of mission in his own work to do with capturing Scotland’s cultural history, usually retrospectively, and laying it down for the present and the future.

Advertisement

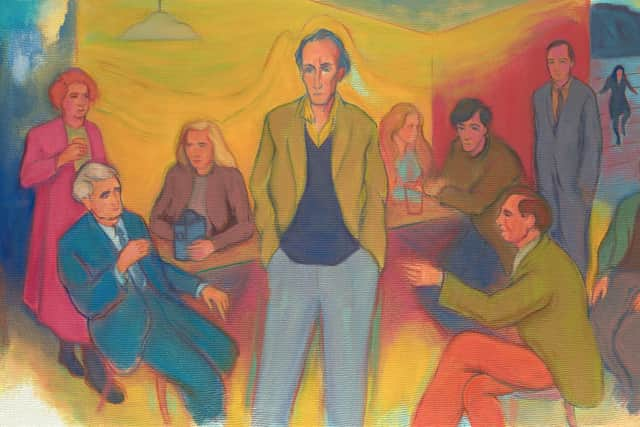

Hide AdThis show, which is almost entirely recent work, includes a new version of his famous group portrait, ‘Poets’ Pub’. ‘Mylne’s Bar’ puts Norman MacCaig at the centre, adds MacDiarmid’s wife Valda and filmmaker Margaret Tait, and nods to the next generation with the distant figures of Moffat himself and John and Helen Bellany coming down the steps.

Here, too, is the companion piece to Poet’s Pub, Scotland’s Voices, a celebration of the folk revival which brings together singers and musicians around the central figure of Hamish Henderson; MacDiarmid, Gramsci and Heine appear as cameos.

Advertisement

Hide AdOther group portraits, always lit with a vibrant colour palette drawn from European expressionism, capture important moments in retrospect. ‘The Border Guards’ brings together the three men who began the Scottish cultural renaissance of the 1920s: MacDiarmid, artist William Johnstone and composer Francis George Scott. ‘Passacaglia on DSCH’ places MacDiarmid with Ronald Stevenson and Dimitri Shostakovich, who met during the Edinburgh Festival of 1962. These meetings of minds give Scotland’s culture a gravitas, place it in an international context. They are serious works with serious intent.

Some of the smaller works have a greater liveliness: here is Moffat’s old friend John Bellany, a young man at the harbour at Port Seton, sizzling with artistic potential; here is Norman MacCaig with the mountains of Assynt behind him; the writer Sydney Goodsir Smith, mid-conversation, cigarette in hand; Alasdair Gray, twinkling with mischief. These works have more lightness, but they might prove equally important in recording the titans of modern Scotland.

One wonders about their legacy. While it’s a delight to see work of this calibre in Dunfermline, might it also find a space to be shown in Scotland’s bigger cities? Might these works find homes in public collections where they can be preserved and enjoyed by the widest possible audience in years to come?

Instant Whip: The Textiles and Papers of Fraser Taylor 1977-87 Revisited, and France-Lise McGurn: What Everyone Wants until 20 April; Alexander Moffat at 80 until 28 April