Scotland farming: 'Ground-breaking' translocation newt project takes place across Highland farmland

The rapid decline of a rare newt species native to the Scottish Highlands could be reversed in years to come thanks to the collaborative work between farmers, ecologists and scientists.

Twenty individual great crested newts have been translocated successfully to various beaver ponds on neighbouring farms in the Inverness-shire area in what is believed to be a first-of-its-kind project to boost population numbers of the protected amphibian.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe species has declined across its European range and is very rare across Scotland. It is the rarest of three newt species native to Britain.

The ponds involved in the translocation project, which has been described as “ground-breaking” work by government agency NatureScot, belong to a group of farmers working together to help wildlife thrive through co-ordinated management at a landscape scale under the West Loch Ness Farm Cluster (WLNFC).

The group includes South Clunes Farm, which reintroduced beavers to the area in 2008, and has seen an impressive wetland area evolve, attracting species including bitterns, otters, African Black Stork and palmate newts.

Some 15 years later, farmer Fred Swift wanted to see what other wildlife could potentially thrive in the wetland habitat, which is when he came across the great crested newt.

These shy animals can be found across the UK, including in various parts of Scotland, predominantly across the central lowlands, Dumfries and Galloway, and the Borders.

There is, however, a specific Highland variety of this species – dubbed the ‘Highland great crested newt’ – that is genetically distinct from its peers across the country, according to scientists.

Research has shown this could be a result of this particular population being isolated from the rest of the British armada some 3,000 years ago.

At first the 80km gap between the newts found in the Highlands and the others in the more central and south areas of Scotland led researchers to believe they were introduced in the north.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut, using genetic techniques to investigate the origin of great crested newts in the Scottish Highlands, research found there is indeed species native to the Scottish Highlands. And it is particularly rare.

This ‘Highland’ great crested newt can only be found in 40 ponds in lowland areas around Inverness and has suffered a serious decline in population numbers.

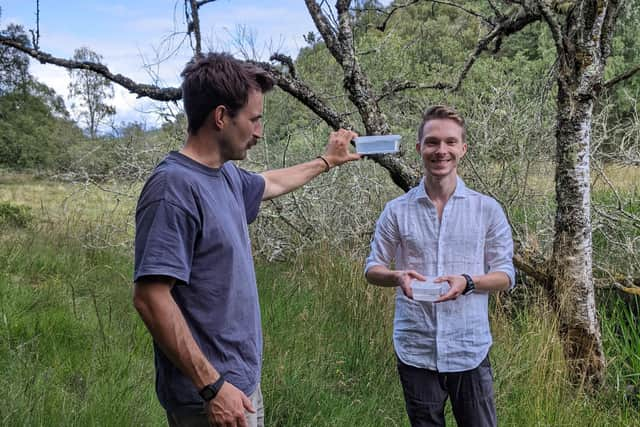

In working with the Highland Amphibians Reptile Project (HARP) and NatureScot, Mr Swift and other members of WLNFC saw 20 of these newts translocated this month.

Danny O’Brien, who works as a ranger for the Cairngorms National Park Authority, but who volunteers his time working with HARP, said the move was believed to be the first of its kind in the UK, and possibly Europe, given the way the translocation has been carried out.

"We haven’t seen any papers written on this specific move of translocating great crested newts to beaver ponds before, which makes us think this is the first time it’s happened,” he said. "We thought the wetlands created at South Clunes seemed like a great habitat for them so we wanted to give it a try.”

Because the species is so rare, Mr O’Brien said eggs were carefully collected from the several of the 40 ponds in the Inverness-shire region where there were already pairs of this Highland variety. Research has shown a female will lay around 200 eggs a year, but there is only a 2 per cent survival rate.

The eggs are then hatched in tanks where the young newts are reared and fed on live prey.

The youngsters are kept for several months until they grow to a size big enough to hopefully ward off unwanted predators before being translocated into different beaver ponds across the WLNFC cluster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It’s a delicate process because they are so protected,” said Mr O’Brien. "You have to be very careful you’re not destroying the donor spots when collecting eggs.

"Down south there are more of these newts and you can just collect a few from a pond to move them. But because there are fewer up here, we have to be more sensitive.”

Despite the delicate and challenging task at hand, Mr O’Brien said the project had been well received.

"What has been really inspiring to witness has been a positive collaboration between ecologists, farmers and scientists,” he said. “Farmers and foresters have definitely been more keen not to destroy the sorts of habitats that support these species.”

WLNFC was awarded funding from NatureScot’s Nature Restoration Fund last year for a “Landscape Scale Wetland and Connectivity Project”, which has helped enable the newt translocation effort to take place.

Mr Swift said the success of the project so far had been thanks to collaborative work between different stakeholder groups.

“I am looking forward to seeing how this project develops,” he said. "Hopefully it will show that where we have beavers in Scotland, we can have other species that thrive including these newts.”

He said the project has also been an important reminder that farmers were “part of the answer to the climate and biodiversity crisis, not the problem”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"You don’t need to choose one or the other – farming or biodiversity,” he said. "The work we are doing supporting the newts on this farm has very little impact on the day-to-day running of the farming enterprise.

“Every farm will have areas that have low agricultural productivity, and it’s about finding those areas that are negative to farming, but that can be used as ecological sites.

"That can be seen with what we are doing with the great crested newt, and it's what we are trying to do through our work with WLNFC.”

A spokesperson from NatureScot said: “We’re delighted to support this work through the Nature Restoration Fund.

"As we tackle the devastating nature and climate crisis, it is innovative projects like this by farmers like Fred, and many others across Scotland, that will help us halt and reverse biodiversity loss and reduce the effects of climate change.

"The ground-breaking translocation methods used in West Loch Ness Farm Cluster for great crested newts will make a real difference for Scotland’s nature, increasing the numbers of the distinct Highland population of this amazing, European protected species.”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.