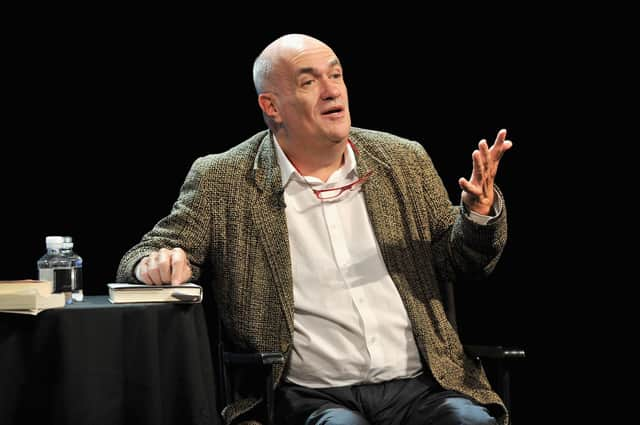

Book review: Vinegar Hill, by Colm Tóibín

That some novelists write poetry and some poets novels is fairly self-evident; but whether they display the same degree of accomplishment in both forms is less certain. One can think of writers such as DH Lawrence or George Mackay Brown or Sophie Hannah where it would be difficult to label them one or the other. There are what we might think of as “occasional” poets, and likewise some poets who through a love of the form, curiosity or economic necessity might eye with envy the advances prose commands. It was with these thoughts that I approached Colm Tóibín’s debut collection of poems. He is a formidable novelist, having recently and deservedly won the Goldsmith’s Prize for The Magician and several times has been shortlisted for the Booker (including in the year when I was a judge). Before the book even arrived I was musing on what kind of poet Tóibín might be. Who are the influences? Who are the precursors? Given that The Magician dealt with the novelist Thomas Mann, and previously The Master was about Henry James, which titular spirits would hover over this?

I did think to myself, I bet Auden and Heaney are in the background. Sure enough, in the second poem, “In Los Angeles” we read “about suffering, of course, / They were never wrong”, though the Auden quote is undercut with “But none of us imagined…” Other poems have a vaguely Beat Poet feel, or the insouciance of Frank O’Hara. I read the book twice, and can say that there are some poems, if not lines, that will stay with me.

Advertisement

Hide AdTóibín’s poetry is, I feel, best characterised as unobtrusive. There are few verbal fireworks or grammatical surprises; and it seems as if he knows this himself. In one poem, “Life”, he imagines a meeting between Gerard Manley Hopkins and the painter Jack Yeats. Hopkins is “at three removes – English in Ireland, a convert / To the Roman church, a poet who is not in print” and is aware that his words are “knotted” and his “words / Are tortured and contrived”. Not so here. The abiding atmosphere is one of lucidity. That is not to say there are not linguistic and rhetorical flourishes. The opening poem, for example, set during the lockdown, talks of “the time after time / What the world will look like when the world / is over” and an acquaintance met in the street has “a watery eye for a watery moment”. That poem, “September”, also has a frequent device, where the end of the poem stages a reversal of tone or aspect, in this case the elderly man saying “Someone told me you were dead”. That falling note is very reminiscent of Philip Larkin. In “High Up”, an elegy, the shine of headlights “hardly / Matters against the strength of things / And then it matters more than anyone supposed”.

Some of the poems are akin to very stripped back short stories. In particular “The Nun” treads the line between farce and bemusement particularly well. “Dublin: Saturday 23 May, 2015” takes place in the wake of the Irish vote for gay marriage and has two unnamed, slightly older characters reminiscing about life for homosexuals in the past: the saunas, the clubs, the fleeting encounters, shot through with a kind of melancholy for repression: “’We could become conspicuous’ one said, / For being not gay enough”. As well as sexuality and meditations on art, there are a number of religious poems, which range between the quietly regretful as in “Bishops” – “No bishop / Could image who / was coming next”, to almost ribald in “Vatican II” and the confusion caused by nuns being allowed to drive. It is a gift to be sympathetic and critical, exemplified in the poem “Kennedy in Wexford”, with its telling lines “I believe that if people had been asked to choose between / A dead bishop and a live President, they would have opted for / The latter”. The observational quality, so essential for both short stories as well as poems, is done neatly in an anecdote poem about how the staff “encourage” guests to leave at White House functions, which nevertheless puts some sharp asides inside the amusement. Vinegar Hill is a fine volume, though I look forward more to Tóibín’s next novel.

By chance another book from Carcanet came my way: The Lascaux Notebooks, translated by Philip Terry from a manuscript by Jean-Luc Champerret. It is claimed he deciphered the abstract petroglyphs in the Lascaux caves, and this is the first “Ice Age” poetry. The introduction claims Champerret was a Resistance code breaker, and I thought, pull the other one, it has bells on. Yet it’s a fascinating and clever book – a fantasy of deciphering, coding, what can be done within limits and limited vocabulary. It is an ingenious puzzle although the backstory rather over-eggs the puddings: I like my hoaxes convincing. It was only looking over my shelves absent-mindedly that I saw that The Penguin Book of the Oulipo – the French movement full of such ludic charms – was edited by Philip Terry. But bravo! I’ve never read anything like it, and that is more than enough.

Vinegar Hill, by Colm Tóibín, Carcanet, £12.99

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions