Artist Charles Avery discusses his ‘island’ realm

A conversation with Charles Avery moves fluidly between two places. One minute we’re talking about his new studio in Hackney, how bright and spacious it is, how he owns it but he had to put in everything, even the floors. And the next, we’re talking about The Island.

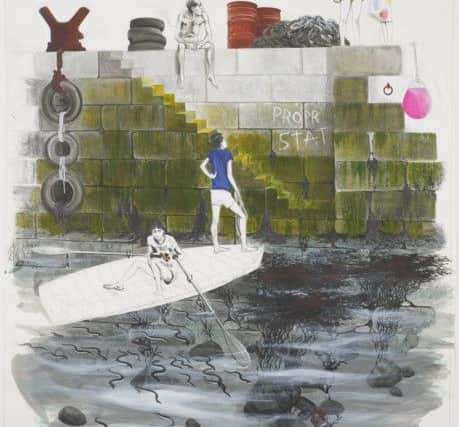

For the last decade, all Avery’s work has focused on The Islanders, inhabitants of an invented country which owes parts to Mull (where he grew up), parts to Hackney, and parts to his own weird and wonderful imagination. His drawings and sculptures explore it in increasing depth, depicting its characters, creatures, topography, belief systems. And he has a disconcerting habit of talking about it in the kind of detail that you might if it was a place just down the road, from the locals’ liking for fried eels to the ostentatious hats bought by tourists as souvenirs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAvery, 42, is an increasingly successful member of Scotland’s current generation of contemporary artists, while at the same time standing a little apart from the crowd. For one thing, he didn’t go to Glasgow School of Art (he went briefly to Central St Martins, but dropped out after six months). For another, while his work is rich in ideas – The Island is a kind of forum for philosophical inquiry – it is not predominantly conceptual. He stands out in the quality both of his draughtsmanship and of his offbeat imagination. Shortlisted twice for the Jerwood Drawing Prize, his drawings have been described by one critic as “probably the finest contemporary figurative drawings I’ve seen in 15 years”.

He believes The Islanders will be his life’s work, culminating in an encyclopaedic book about the Island which will encompass all the art he has made. “It makes me anxious, though, when I think how far away I am from that point. It’s an easy game to talk, The Islanders, it’s a much harder thing to acquit, I’ve discovered.” Does he ever wish he could just go off and make art about something else? “Not really. Sometimes I feel miserable that I can’t leave it behind me. There is great pain in not being able to put something behind you and say it’s in the can. If I die tomorrow, it will not be complete. I carry those anxieties.”

However, as he talks about his new show at the Ingleby Gallery for Edinburgh Art Festival, The People and Things of Onomatopoeia (the Island’s main town), it becomes clear that the project is still inspiring him to diversify in all kinds of interesting directions, from making eels out of blown glass (“like drawing, in a way, the speed you have to work at”) to designing the Island’s tables and chairs.

“The Islanders avoid the number four, they avoid the quadrilateral,” he explains. “So they tend to go in for three-sided tables and five-sided tables. They feel that a four-sided table produces awkward confrontation, a three-sided one promotes more comfortable relations.” He likes designing furniture, though. There might yet be a whole show of it. “It’s quite a relief for me to be making things like that. You can make a perfect chair, go through six or seven stages of refinement and then you end up with the right answer for that chair. Whereas you can never make a perfect drawing. Drawing’s just an endless pain. Or it is for me.”

While he says The Island is simply “another place”, not created, like the islands of Jonathan Swift or Thomas More, to comment on the present world, it does have some remarkable parallels. Take Onomatopoeia, for example. It grew from frontier town to boom town, before experiencing years of post-industrial slump. Now it has been regenerated in the name of cultural tourism, with a Guggenheim Bilbao-style Museum of Art, and an endless philosophical debate in its pubs much enjoyed by visitors. “There are a lot of buildings going up at the moment, the town is feeling the effects of globalisation. New things are going up for the tourists, but you still have the disenfranchised mendicants and itinerant workers around the docks. My idea of what The Islanders would be has changed. I did set out with a lot of invention in mind, and the more I did that the more I found new fascination in the real world. I realised I needed to acknowledge the trade with this world.”

This exhibition, however, aims to capture something of the “texture and everyday life of the islanders”, hence the tables and chairs, and the eels (we have a long discussion about eels, how he sent his assistant to buy one at Billingsgate Market, which he then had to bludgeon to death with a wrench. “It took about 20 blows, bloody unbelievable, such brutal, primitive beings – we turned it into Galician stew, so it didn’t die in vain”). And the metal trees from the Jadindagadendar, Onomatopoeia’s main municipal park: “Actually, they’re a refutation of nature, all the trees are man-made and mathematical, they don’t reproduce, they don’t need to, they’re eternal”. A five-metre high specimen, cast in bronze, will be installed in Waverley Station near the Calton Road entrance as one of Edinburgh Art Festival’s public commissions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAvery is pleased about the tree, about the idea of taking art beyond the gallery walls. “This is a very public-facing project, I see it as being egalitarian. I see it as being very accessible to a huge range of people, and I want to embrace that. I do feel that the art world has egalitarian pretentions but isn’t egalitarian. There’s definitely a bit of a habit of obfuscation, and some sort of pride taken in that, almost that it’s a sign of good art because it’s completely obscure. I find all that a bit much.”

By contrast, he hopes The Islanders will be a “a forum for other people’s thinking”, a “gymnasium”. He’s delighted by the idea of other people exploring ideas within the structures of his invented world. “I think the project as a whole, when it reaches its critical mass, could be used in schools. We had to do religious education, and I think that needs to be a more secular subject now, but nevertheless it’s very important to humanity to take on metaphysical issues, on a philosophical rather than a religious basis. I think the book could be a useful place to talk about simple ideas because The Islanders doesn’t take a position.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAvery seems content with his place in the art world, slightly to one side of the mainstream. “I hesitate to say what this project is, and what category it falls into. Nevertheless, the contemporary art world provides a framework, a support structure for people who fall into the gaps.” And he adds that he’s grateful for “charming collectors who really follow the project – I don’t attract oligarchs, as a rule.”

And we talk about art on the island, where the key concept is “sendenda”, literally “a ghost”. “As an artist, what you do is try to create a structure which is inviting to the ghost, so that it might come and reside there. Though there’s no guarantee that it will continue to do so. That is a satisfactory explanation for the way that some art work becomes relevant over time or ceases to the relevant: the world changes. But the art work is not the art, the art is the ghost.” He pauses for a moment. “That’s my philosophy as well, but I’ve sort of imposed it on to The Islanders.”

• Charles Avery: The People and Things of Onomatopoeia, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh, 30 July until 30 October, www.edinburghartfestival.com