Art reviews: The Art of Wallpaper - Morris & Co | James Hugonin | David McClure

The Art of Wallpaper – Morris & Co, Dovecot, Edinburgh *****

James Hugonin, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ****

David McClure: A Sicilian Story, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide Ad

Wallpaper! Just so much bland wall covering, not worthy of our attention? The Art of Wallpaper – Morris & Co, the new show at Dovecot, aims to make us think rather differently and that it is a serious field of design, really an art form in fact. It also explores how William Morris’s own commitment to wallpaper design was in order to make beautiful decoration available at low cost for quite modest homes. This was an evangelical mission. Morris followed Ruskin to argue for the intimate relationship between art, design, workmanship and quality of life.

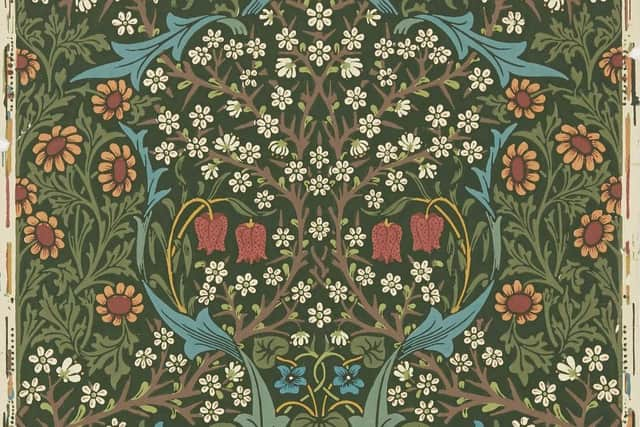

The show draws on the unique archives of Sanderson and Co. Involved with wallpaper since 1860, the firm latterly became heirs to the wallpaper catalogue of Morris & Co, the firm that William Morris himself set up in 1875 and which continued trading, although not just in wallpaper, until 1940. The Sanderson archive holds a remarkable record not only of Morris’s own designs, but also of the wider revolution in wallpaper design and production that was led by the Arts and Crafts movement from the 1860s onwards. The leaders were Morris himself and other key figures in the wider history of design such as Augustus Welby Pugin, Owen Jones, Christopher Dresser, Walter Crane and CF Voysey. Owen Jones's Grammar of Ornament published in 1856, for instance, was a key document in the history of design. He argued that good design should not imitate nature, but abstract from the patterns it displays. His book is primarily visual, too, illustrating examples from every major tradition of design, including the so-called primitive art of the South Seas, all printed in brilliant colour using the new chromo-lithographic process.

But a certain Harold Potter also played a key role in all of this. He may not have been a wizard like his namesake, but the machine he patented in 1839 did seem pretty magical. It was a four-colour, roller printer. Using new oil-based inks it could produce 400 rolls of wallpaper a day. A wallpaper tax had recently been dropped, so conditions were propitious for a dramatic expansion. French wallpapers, block printed in highly ornamental, naturalistic styles, were the fashion. There are striking examples here both of these French papers and of home produced papers in the same style. Sanderson himself began by importing these French designs, but in 1879 established his own factory. Apparently these high-coloured wallpapers weren’t a suitable background for aristocratic family portraits. Something more sober was needed. This was a rather different motivation for a shift in style from that professed by William Morris, but it was all part of the mix and new flatter, more formal patterns were first pioneered by Pugin and Owen Jones. In the 1840s, Pugin’s medieval influenced designs for the new Houses of Parliament were early examples. (They also caused a huge row a 150 years later, when in 1998 the Lord Chancellor, Derry Irvine, restoring Pugin’s decor, installed them at great expense in his official lodgings – plus ça change.)

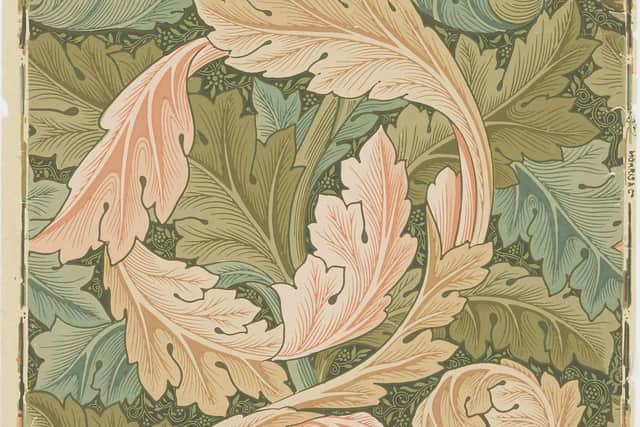

Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co was set up in 1861. It was the first firm established by Morris and his friends and he began to produce wallpaper designs in 1864. His first was Trellis. A design of a trellis of briar roses with birds and butterflies, it took 12 blocks to print. He also produced Daisy in the same year, however. Based on the floral decoration in illuminated manuscripts, it is much simpler and became one of his most widely imitated designs. He also began to produce more overall designs like Leaves, for instance, which only took two blocks and so were much cheaper. Morris may have wanted tor reach a wide public, but he also decorated Balmoral, designing a paper with the Royal cypher and a thistle. Morris’s designs were printed by the firm of Jeffrey and Co. who also employed a variety of other leading designers and there are beautiful patterns designed by them on show.

A set of the massive blocks for Morris’s Chrysanthemum design is displayed here. They are very impressive objects and give a sense of the manual skill that went into all of this. As he does in Chrysanthemum, Morris generally sticks to two principal layers and a ground that together combine to create broad rhythms against a field of satisfying visual complexity. Willow, slender willow leaves and curving branches still popular today, is another wonderful example. Its inspiration came while walking among willows by the Thames with his daughter, May. May herself also contributed patterns and one of the most impressive things about the whole enterprise is what a high standard of design the Morris team managed to maintain even after his death. It was his pupil, John Henry Dearle, for instance, later artistic director of the firm, who designed some of the most enduringly popular of the “Morris” designs like Golden Lily or Bird and Pomegranate.

The justification for having this show at Dovecot, a tapestry workshop, is that historically tapestry covered walls and so played the same role as wallpaper. It was certainly in a different price bracket although there is at least one wallpaper here which, with its price converted, would cost several hundred pounds a roll today. In the 17th century, there was a fashion for embossed leather wall covering. Like tapestry, it was warmer than bare stone or plaster. The Japanese took to this fashion and lacking leather copied it in paper. These papers were later exported back to the West, creating a vogue for heavy embossed wallpapers. Morris himself did do designs in this mode, printed in Japan, and also sold there. But they are something of a diversion here from the main design story that is told so well: the evolution of the absolutely classic wallpaper designs of the Morris firm. Never out of fashion, some of them seem to have been in constant production for a century and a half.

Advertisement

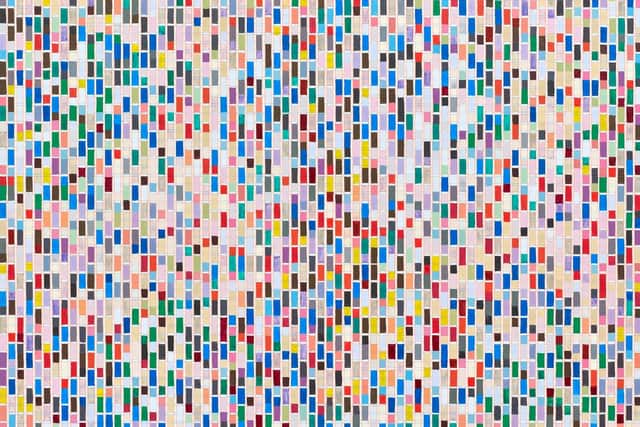

Hide AdYou might mistake James Hugonin’s paintings at the Ingleby Gallery for wallpaper. They are flat and painstakingly composed of a regular grid of tiny, coloured rectangles. The rectangles are aligned vertically and each has a distinct colour. At first they look static, but the effect of this pattern of constant colour change is actually dynamic. Other wider patterns appear as though we are looking into shifting clouds or falling water. The effect is engrossing and, the six large pictures, all in the same format, look grand and solemn.

If James Hugonin’s execution is so tight you can almost hear the tension squeaking, David McClure’s painting celebrates freedom and delight in things. A small exhibition at the Scottish Gallery is devoted to pictures of or inspired by Sicily where he sent six months in 1956-7. A group of poetic townscapes and landscapes were painted then and there, but he also later returned to the inspiration of Sicily to paint darker more emblematic pictures of church interiors and rituals with hints, too, of Mafia violence.

Advertisement

Hide Ad

The Art of Wallpaper – Morris & Co until 11 June; James Hugonin until 26 March; David McClure until 26 February

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions