Nick Mevoli, the freediver who died chasing a record

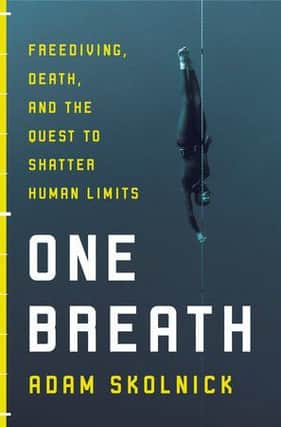

One Breath by Adam Skolnick | Corsair, 324pp, £20

The best reporters are like verbal cameras – they don’t just tell you what happened, they show you. On the evidence of this vividly written book, Adam Skolnick is a very fine reporter indeed. In 2013, he was sent to Long Island in the Bahamas to cover a freediving competition for the New York Times, and while he was there one of the athletes, Nick Mevoli, 32, was killed while attempting to dive to a depth of 72m on a single breath. Skolnick had only known Mevoli for a few days before disaster struck, but – as he puts it in his acknowledgements – he had already realised that he was special. “He possessed an uncommon generosity of spirit and time, his heart was big, his soul was real, and his actions backed it all up,” he writes. Skolnick resolved to try and tell Mevoli’s story, and One Breath is the result – heartbreaking and inspirational in roughly equal measure.

It seems hard to believe, but before 2013 there had never been a fatality at an international freediving competition. At the time of Mevoli’s death, the world record for Free Immersion – the category he was competing in, in which divers have no propulsion equipment but may pull on a rope to aid ascent and descent – was an astonishing 121m. At time of writing, that record, set in 2011 by the New Zealander Will Trubridge, still stands. At those kinds of depths, the body is put under immense strain. Even at 70 metres, about the depth Mevoli was aiming for, pressure is almost 17,000 pounds per square foot and the only reason the human skeleton doesn’t simply collapse, Skolnick explains, is because blood vessels in the arms and legs involuntarily constrict, pushing blood to the core of the body and essentially filling what would otherwise be a vacuum with liquid, which can’t be compressed (think of what happens to an empty water bottle on an airliner, and what happens to a full one). But just because the human body has a clever way of dealing with all that pressure doesn’t mean it’s immune to damage, and, as Skolnick discovers, at the time Mevoli died professional freedivers would often experience “lung squeezes” causing micro-tears to their alveoli that would leave them coughing up blood. Indeed, it seems Mevoli himself may have been suffering from a squeeze on the day he died, but the prevailing wisdom at the time was that “bloody lungs heal fast... and if an athlete wants a record bad enough... it’s best to tune out the negative chatter, prove everyone wrong, and go for it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf the cavalier approach to lung squeezes in freediving led to Mevoli deciding to make his fateful dive, Skolnick suggests that the first aid he received once he’d surfaced, obviously in difficulties, left a lot to be desired. In fact, his analysis leaves the reputation of the emergency doctor in attendance in tatters. I’m not convinced the physician in question deserves quite the level of criticism she receives, but anyway, it’s a moot point – this book is really more about celebrating Mevoli’s life than investigating the circumstances of his death. Skolnick shows us a young man who overcame the pain of a difficult upbringing and channelled it into some remarkable achievements, both as an actor (he starred in the 2004 indie film exist) and as a diver. His perpetual restlessness may have caused heartache both for him and for those around him, but it was also the source of his greatest triumphs; if Nick Mevoli was a tragic hero, this was surely his tragic flaw.