Scotsman 200: Literary characters captivate the world

Saturday, 3 January, 1818

Literature: Rob Roy

3 vols 12mo, Edinburgh, Constable & Co.

We do not think this new novel will disappoint the long-suspended expectations of the public. Although inferior in point of novelty and strikingness to “Old Mortality,” it may be considered as a very fair match and addition to the three former novels, generally ascribed to the same author.

Waverley is perhaps the one to which it bears the strongest resemblance; a good many of its scenes being laid in the Highlands, and the story being, in some measure, connected with public events.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo give an abstract of the story would be doing an ill turn to those who have not yet read the book. The charm of suspended curiosity is a sacred thing, and must not be broken by idle babbling and premature hints.

We shall not, therefore, unfold the tale, but allow it to remain wrapped up in the mysterious and tempting obscurity of a bookseller’s advertisement, nine months previous to publication. We have no doubt but the bookseller and the book are now doing “as well as can be expected,” and Rob Roy will turn out as fine a child as any of the same family.

The Highland hills, glens and rivers are brought before our eyes with such admirable skill that the sheet of printed paper upon which we are poring seems to vanish altogether, and a moving camera obscura is substituted in its place, where the branches of the trees are seen stirring, and the brooks leaping and gurgling, as if it were actual nature.

The author does not strive to astonish by overcharged descriptions of an ideal grandeur and beauty, but rather accomplishes his purpose in the manner which painters ascribe to Titian, when he paints landscapes, that is by certain well-chosen strokes of the pencil, which strongly recall to our minds the characteristic and peculiar qualities of each object.

In attempting to represent a landscape by means of language, the great difficulty is to avoid confusion; which is best done by studying how to illuminate the parts, in the same order as they attract our attention, when subjected to ocular observation. If we may judge by the result, the author of these novels possesses that art in a very high degree.

The novel of Rob Roy has also its share of genuine Scottish characters. These are Andrew Fairservice, a gardener, who is first met with on English ground, and afterwards becomes a servant to the hero; and a most exquisite Baillie Jarvie, of Glasgow. The features of Andrew Fairservice are new, and different from those of any of his countrymen formerly brought upon the stage.

There is a very noble and imposing account of Glasgow Cathedral. Nothing can be finer than the strain of sentiment that is mingled with it. Another thing which shines forth as a brilliant part of the narrative is the scene at a Highland inn, with the subsequent encounter between a troop of English soldiers with the wild Highlanders. Rob Roy’s escape in crossing the river Forth is also an amazingly vivid description.

Saturday, 28 October, 1961

New Novels: Opposites united in experience

Prime and decline

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdReading Muriel Spark’s novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (from Macmillan on Monday; 13s 6d) one realises the virtue of the economy, the value of allusion, of almost casual asides, in conveying essential facts in a narrative.

Some novelists (naming no names but glowering across the Atlantic) would have magnified this story of a distinctly unorthodox schoolmistress and her pupils into 1000 pages.

Briefly, but not without poignancy and certainly with much irony, Miss Spark describes her Miss Brodie’s prime, decline and fall, betrayed in the end by one of her pupils whom she had, in her own peculiar way, formed for life.

We see the “Brodie set” as a group of girls of 16 in the Marcia Blaine School in Edinburgh; glance back to their childhood in the junior school when they fell captive to Miss Brodie’s unusual stimulus; return to their teens; are told, in aside, what happens to them in maturity; and see them finally in that maturity, Miss Brodie dead but remembered.

The period is the ‘30s. The pattern of interwoven destinies is beautifully clear. It is all presented with detachment, with an objective attitude to morals. Miss Brodie claims descent from the adaptable Deacon of that name, and certain episodes in her private life would not commend her to parents; one of them, her disposal of two of her pupils to a male colleague with whom she is herself in love, is not convincing.

But a new quality has crept in: a compassion not discerned before in Miss Spark’s brilliant but somewhat heartless work. The drama of personalities turns from comedy to tragedy.

The narrative, in both dialogue and comment, is crisp and sparkling with wit: in so few words this author can convey so much. One can perceive a spiritual kinship with I. Compton-Burnett, but with this added capacity for pity.

Thursday, 20 November, 1997

Coffee in one hand, baby in another: a recipe for success

By Judith Woods

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA woman sat in the corner of the busy cafe, pen in one hand, espresso in the other and baby in a pram by her side. Around her plates clattered, waiters tripped backwards and forwards in their starched white aprons and the customers chattered over pains au chocolat.

The woman didn’t seem to notice the chaos in the large wooden-floored space. She was writing a children’s book and the only place she could find which was warm – and for the price of a 90p espresso would let her sit quietly all day – was Nicolson’s cafe on Edinburgh’s South Bridge.

When children’s author Joanne Rowling recalls her darkest days, there is a shiver in her voice. But the poverty, the depression and the clammy chill of her one-bedroomed Edinburgh flat where the single mother who had fallen on hard times sought to keep her baby daughter warm, pall in comparison to the looming loss of her identity.

“The feeling of who I was was badly damaged by suddenly finding myself a single parent on benefits,” says Rowling. “So I wrote to protect my sanity. I have always written and so it was a way of continuing to be me, despite all the ghastly circumstances.”

There is no romance to the starving-artist-in-a-garret existence at the best of times. With a baby to feed and clothe and fret over, it possibly constitutes the worst of times.

“There were times when Jessica ate and I didn’t. I feel like it’s a case of ‘cue the Hovis music’ when I say that, but it’s true, however it sounds.“When I fetched up in Edinburgh I was pretty much penniless and it was a complete shock to my system.”

Her marriage to a Portuguese TV journalist had disintegrated when their daughter Jessica was just three and a half months old and she had moved to Edinburgh to be with her sister.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRowling, 32, has just picked up a prestigious literary award, the Nestle Smarties Book Prize, for her children’s book Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. It is the latest success in a string of events which have seen her rocketed into the league of high-earning professionals, with rival companies bidding for the film rights and a massive six-figure advance.

Nursing a single cup of coffee, she sits in a cafe for hours, and, as her baby daughter sleeps, in laborious long-hand she feverishly writes a children’s story about a lonely little boy, Harry Potter, who escapes his Dickensian misery by becoming a wizard.

The magic is catching. When she sends off the manuscript, to an agent, it is admittedly more in hope than expectation, but a fairytale ending is in store: a £ 100,000 US publishing deal for the first of seven books, and four companies, two of them Hollywood studios – tussling for the movie rights.

Yet if this rags-to-riches tale of real-life smacks, unavoidably, of cliche, the resulting fiction has been hailed as inventive story-telling at its best.

Potter, a little orphan boy, is persecuted by his nagging relatives until at 11 he boards the train for Hogwarts School of Wizardry and Witchcraft, after which his life will never the same again.

The same can justifiably be said about Rowling herself. Still based in Edinburgh, the city she “instantly fell in love with”, her living conditions are a far cry from her first dank city-centre flat.

But her experience of the rough end of life has been a salutary one and she remembers the little kindnesses rendered to her in times of need.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is an escapist book and by writing it I was escaping into it. I would go to Nicolson’s cafe, because the staff were so nice and so patient there and allowed me to order one espresso and sit there for hours, writing until Jessica woke up. You can get a hell of a lot of writing done in two hours if you know that’s the only chance you are going to get.”

For its part, the cafe staff was quite happy to let inspiration take its course. “We all know Joanne and Jessica,” says general manager Roland Thomson.

“They would come in almost every day, and the wee girl would sleep while her mother wrote. It was really sweet.” Rowling says her sympathies go out to single parents in a similar position, while acknowledging that her good fortune is not the kind of thing everyone in the poverty-trap can realistically emulate.

“When Harry Potter was published there seemed to be an aura of amazement that a single mother could produce anything worthwhile, which is pretty offensive.

“I would hope that other women would see what I’ve done as inspirational, but on the other hand I know I was very lucky.

“I had a ‘saleable talent’, to put it crudely, and I also had an education, so even if I hadn’t written the book I would have had the raw materials to rebuild my life.”

The staff at Nicolson’s make no secret of their pride at Rowling’s success. She is still one of their most regular customers, but in one respect at least fame has changed her: now she can afford to eat lunch.

Sunday, 26 January, 1997 (Scotland on Sunday)

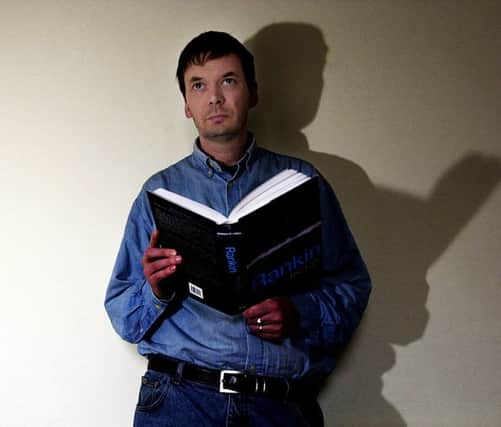

Hard-bitten moral crusader with a touch of the poet

Black and Blue, Ian Rankin: Orion, £19.99/£9.99

By Peter Whitebrook

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough Ian Rankin uses much of the equipment of the detective genre, his ambitions are clearly those of the literary novelist. His fiction fizzes with energy, strains with ambition.

His books are tales well told of crimes solved, yet order is never wholly restored from chaos and there is always the disturbingly pervasive sense that the devil, once inside us, leaves an indelible impression. Yet Rankin has enormous compassion.

Essentially, he is a romantic storyteller in the tradition of Robert Louis Stevenson, yet at the same time he is a harsh moralist, and the edges of his world are bleak and unforgiving places indeed.

The ninth Rebus novel is not only the longest but the most intricate, involving a serial killer seemingly emulating the Bible John murders in Glasgow 30 years ago; the violent death of an oil worker in an Edinburgh tenement; a family of Glaswegian gangster overlords, and an official investigation into Rebus himself after a prisoner alleges a miscarriage of justice.

Rankin controls the material with extraordinary authority and even delicacy, developing his perennial themes of the effect of the past upon the present, allegiance and betrayal, and the cost of friendship.

Rankin ranks alongside P D James and Michael Dibdin as Britain’s finest detective novelist.

Yet Black and Blue feels less like an achievement in itself than a novel which may come to be seen in retrospect as the bridge between one phase of work and another. It seems like a transitional novel, and in places not quite as confident as the earlier, and excellent Mortal Causes and Let It Bleed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor a start, Rebus seems lonelier than ever. He still sleeps most nights ascetically shrouded by a blanket, in a chair by a window in his Marchmont apartment.

This is a place of famously belching central heating and where the furniture consists of not much more than a bottle of whisky and a pile of old Rolling Stones records.

There is no sign of Dr Patience Aitken, who for a long time provided tea and sympathy at Oxford Terrace, nor of Sammy, his daughter.

And Rankin seems as circumspect at times as Rebus. Although working on a larger canvas, his stylistic palette is still that best suited to the preceding, shorter and more compact novels.

He sets up the plotlines as deftly, and as economically as ever: but perhaps in a novel of almost 400 pages, rather too deftly, rather too economically.

Greater length calls also for a greater tonal range in the writing, and although one never wants to abandon the book, one longs for something more daring in the language, technical and stylistic experiments that come as a real surprise.

The anticipation is high: Rankin will write a very important book very soon.

The full text of the edited extract on Rob Roy can be found at The Scotsman Digital Archive.