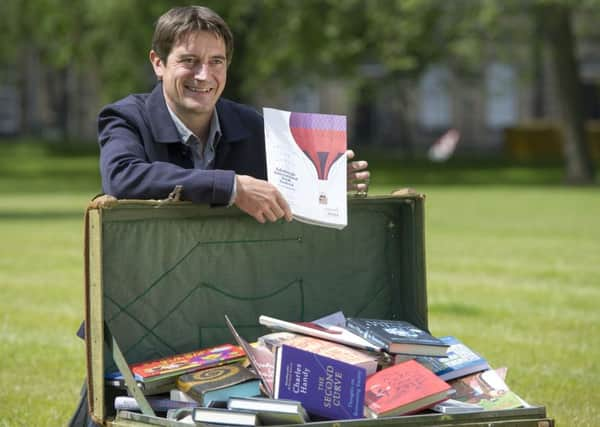

Nick Barley on the book festival’s foreign voices

IAM reading, right now, about violence. It’s a thoughtful essay about what makes us look – even though we might hate ourselves for looking – at pictures of killing, and it drops all the right references: Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others, Anthony Burgess and A Clockwork Orange; and the story from Plato’s The Republic of Leontius, who was disgusted with himself for wanting to look at the bodies of freshly executed men but couldn’t stop himself doing so all the same.

I turn a page, and the essay lurches into horror. Because Mexican journalist and novelist Sergio Gonzalez Rodriguez is no longer writing about violence in the abstract. He’s writing about being filmed watching a film of a man in a Punisher mask (like the Marvel Comics figure) lead other gang members in emasculating and then decapitating by chainsaw a blurry but very real human being. And Sergio Gonzales Rodriguez, I should add, knows his subject all too well. He has himself been tortured by the drugs gangs of Mexico and has the scarred thighs to prove it. He has been warned that he’ll be murdered unless he stops his investigative journalism. He hasn’t and won’t.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat on earth, you might wonder, has he to do with the poet Josephine Bacon, who grew up on the north coast of Quebec, where her parents were the last generation of Innu nomads? And what have either to do with Alain Mabanckou, the writer from the Congo who has been compared to Salinger by the French Nobel laureate JMG Le Clézio?

OK, you’ve guessed. They’re all going to be at the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s tented village in Charlotte Square this month. The programme is indeed, as director Nick Barley claims, the festival’s most international yet. What’s fascinating is how it got to be that way.

Many of us don’t think about the network of links, recommendations, friendships and literary truffle hunting that underpins the Book Festival programme. But it is almost as intriguing as the stories themselves.

A BET IN GUADALAJARA

A COUPLE of years ago, when internationally famous Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco had an exhibition at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery, Nick Barley took him out for a drink at the Scotch Malt Whisky Society. (A bit of background here: the Fruitmarket’s director Fiona Bradley is Barley’s wife). Over a dram, as Barley extolled the contemporary Scottish literary scene, Orozco pointed out that its Mexican equivalent was equally exciting, but completely ignored over here. At which point the thought crossed Barley’s mind: How about a Mexican strand at the Book Festival that would show us just what we’re missing?

He next met Orozco at the Guadalajara book fair last November. “I said to him, ‘You remember what you said last year? I’m going to take you up on it. If I said you could bring over five or six Mexican writers whose work really matters to you but who haven’t been published in the UK, who would you pick?’”

Within a day, he’d got a list, then he set about meeting the seven writers Orozco chose. It only took a couple of days – he flew to Mexico City for lunch with the last of them – and he returned to Edinburgh. Which is why this year’s programme features seven leading Mexican writers in three events – two novelists, two essayists and three poets – and we can, for the first time, judge for ourselves.

Nor does it end there. Maybe next year there’ll be a Scottish writer or two at Guadalajara, maybe in a year or two, Barley’s hopes that a British publisher will latch on to one of his seven Mexicans will be fulfilled; either way, the festival has also produced a neat booklet – free – with samples of their work. That’s how I know about Sergio Gonzalez Rodriguez, though in fairness I should point out that his essay about gang violence comes just before a lovely short story by Juan Villoro about a man who uses his car as a crèche. Mexico may be badly scarred by drugs violence, in other words, but there’s far more to its literature than that.

THE CONGO SUPERSTAR

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIT’S easy to tell where power lies in Brazzaville – it’s in those places where the floodlights never fail even in the blackouts – the Chinese-built foreign ministry, for example, or the 1970s neo-brutalist Palais des Congrès, a little-used parliament across the road.

In February 2013, they held a literary festival in the Palais. Its creative director was Alain Mabanckou, the Congo writer shortlisted for this year’s Man Booker International prize.

In the Republic of Congo, he’s a literary superstar, often routinely mobbed by his fans; in the US (where he teaches at UCLA) he’s mistaken for Samuel L Jackson (“he’s SO much older!” he complains); and in France he is routinely hailed as one of Africa’s finest writers. In Britain, apart from those who have read his moving memoir The Lights of Pointe-Noire or the three other of his novels also published by Serpent’s Tail, he is all but unknown.

When Barley spotted him at the Brazzaville writers’ festival, they already knew each other. Barley was there with some of the contributors to the Edinburgh writers’ conference the previous August; that accounted for five of Etonnants Voyageurs’ 50 events, but they wouldn’t even have been invited if Edinburgh had not already struck up a good working relationship with the French literary festival of St Malo, where he is a regular guest. One time there, he found himself sitting between Mabanckou and his wife.

He’d already read a couple of Mabanckou’s novels, one of them in 2012 when he had been a judge on the Independent’s Foreign Fiction Prize. “He was coming to my attention again and again,” he says, “and every time I saw him I was impressed and everything I read by him was impressive too.”

In 2013 Mabanckou took Barley to Pointe-Noire, the coastal city where he grew up, and showed him where the slave ships once sailed, carrying 1.3 million Africans to plantations across the Atlantic.

It’s also the place Mabanckou revisits in his memoir, The Lights of Pointe-Noire, published in May, a bittersweet reflection on the country he left behind for 23 years and the mother for whose funeral he didn’t return.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdListen to Barley talk about Mabanckou and you see not only why he wanted to invite him but the filigree of interconnectedness behind the invitation: that Brazzaville conference in what is essentially a dictatorship at which writers from all over Africa were suddenly and surprisingly free to talk; the writer’s memoir opening western eyes to postcolonial African life. “Literature is a lens through which we can look at the world and make sense of what is going on,” says Barley, “And there are so many reasons Alain Mabanckou’s writing touched me. How much, in all honesty, do we know about central Africa? Yet his story – growing up in a country whose natural resources are colonised in the capitalist way, leaving people to get by in massive poverty – was, I realised, happening all over the world.”

QUEBEC’S NORTHERN LIGHTS

The first time Barley travelled abroad to an international book festival – Perth, Australia in February 2010 – he didn’t realise that within years he would be spending up to ten weeks a year doing just that: building up a network of mutually supportive literary festivals throughout the world (Beijing, Berlin, Toronto, Melbourne, Jaipur, New York, St Malo) and checking out others to add to the list. But there are book fairs to go to as well, because it’s there he can meet literary agents and publishers. As an example of the importance of the latter, Barley tells me about Haruki Murakami’s event last year at Edinburgh. It had taken five years to set up, and only happened because Random House London was able to persuade the rest of Murakami’s English language publishers to shift publication dates forward to the end of August.

It was at a book fair – in Montreal, late last November – that he first heard poetry in Innu-aimun (native speakers: 11,080) from the far north of Canada. “I met representatives of a small publisher who specialises in ‘first nation’ writing, and they told me about Josephine Bacon, and how she was a superstar of indigenous culture. She was giving a performance at a small theatre in north Montreal. I went along and these three writers – Josephine Bacon, Naomi Fontaine and Natasha Kanape Fontaine came on stage and started to perform a mixture of singing, chanting poetry and prose. It was unutterably beautiful, straight from the heart, and I’m sure it will move people who see it. I was sitting next to a tribal leader and I asked him about the three women. ‘They’re so important,’ he told me. ‘They carry the torch for our traditions, and without them they would be dying.’”

So into the programme it goes, another set of voices you might never have expected to hear. And maybe never would, at least not all together, anywhere else apart from the world’s biggest and best books festival.

• Mexican writing: 17 (7:15pm), 18 (12:30pm) and 19 August (2:15pm) (fiction, essays and poetry respectively). Innu-aimun poetry: 29 August (with Scotland-based poets), 11am, and 31 August, 3:45pm. Alain Mabanckou: 18 August, 7pm.