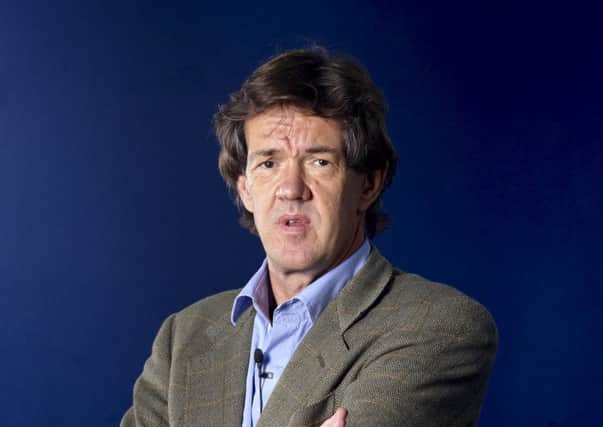

New book sees Robert McCrum getting to grips with death

We are sitting on a sofa in the atrium of King’s Place, the building where he works as an associate editor of the Observer. We’re talking about his new book, Every Third Thought (the title comes from Shakespeare’s Tempest: “And thence retire me to my Milan, where every third thought shall be my grave”). It’s about – well, it’s about death. And big questions. The Gauguin questions.

They are not questions to which there are easy answers. McCrum says he becomes painfully aware of this when he appears at book festivals - as he will in Edinburgh tomorrow, when he will be interviewed by Richard Holloway – and sees rows of faces hoping for some privileged insight. “If you’re talking about a novel or a biography, you, as the person who wrote the book, know more than the audience. In this case, I’m no expert. We’re all in this together. I’m just someone who has spent time thinking about this.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe has been thinking about it for more than 20 years, ever since he was felled by a stroke in 1995 at the age of 42. He was off work for a year, but made a good recovery; he wrote movingly about the experience in My Year Off, which is now a Picador Classic. However, he still experiences weakness in his left side, types one-handed, walks with a stick. When the time comes to rise from the sofa, he leans on it awkwardly, heavily, until his legs start to obey him.

He describes Every Third Thought as “a book I didn’t have much choice about – it comes from the heart”. “I’ve spent half of my [adult] life now, since the stroke, in the psychological equivalent of A&E. I suppose I had quite a burning need to come to grips with a subject which is very hard to come to grips with. I’ve always grappled with these things by writing about them.”

A fall in the street felt like a reminder of mortality, and, while he had his first brush with death more than 20 years ago, suddenly his friends were having them too. “In the last six months, three friends have died, all in their sixties. One of them went to sleep and his wife woke up the next day and found him dead. He was somebody I travelled around Europe with as a hippyish teenager in 1970, and now I’m at his funeral. It’s hard to escape that.

“You’d have to be very cavalier not to pay attention to the invasion of mortality.”

His approach to the subject is, perhaps not surprisingly, to reflect on it through the lens of literature (he is the author of two books on the English language and a biography of P G Wodehouse as well as several novels, and was editor-in-chief at Faber & Faber before joining the Observer as literary editor). He also interviewed doctors, neuroscientists and people suffering from terminal illnesses, and collected all manner of anecdotes about death, not all of them gloomy.

One of those interviewed for the book is writer and broadcaster Clive James, whose obituary McCrum wrote in 2015 when he was believed to have died after a battle with leukaemia (James is still alive, and now writes a column for The Guardian called Rumours of My Death). “He wrote this poem about death called Japanese Maple which went viral, about this young tree in his garden, how it would live on and he wouldn’t be there to see it. Everyone was saying what a great poet he was, what a great last poem. You go and visit him, he’ll point it out, its in his backyard, it’s no longer a sapling, it’s a great big Japanese maple. He’s quite embarrassed by it. It’s both funny and sad at the same time. But I think the funny/sad thing is worth hanging on to if we’re not to plunge into a black hole of despair.”

By and large, he says, his generation will do anything to avoid talking about death. “The Baby Boomers have been encouraged to think they’re immortal, and to fulfil themselves as much as possible, to live as though they would live forever and not to accept any restrictions on anything. And suddenly, they’re being constricted by physical decline and by the narrowing of horizons. It’s very frustrating.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMedical advances have done much to prolong life, but, he points out, death hasn’t gone away. “Saying that 60 is the new 40 is a typical Baby Boomer fantasy. It’s a classic example of what people like [neurosurgeon] Henry Marsh would call cognitive dissonance: holding something in your head which completely conflicts with what you know, rationally and intellectually. I think 60 is the new 60.”

But there is something in all this talk of death which is surprising: it keeps redirecting us back to the subject of life. The big questions – the Gauguin questions – are not actually about dying, they are vital, burning questions about living. Awareness of one’s mortality just paints them in stronger colours. And while they might well be unanswerable, there is value – or so it feels – in asking them anyway, and taking time about it.

Sooner or later, in doing so, one washes up against the problem of God. McCrum says he “fudges” this in the book. He says he “doesn’t really” believe in God, and he doesn’t believe in the afterlife. “But I believe in religion. Last year, I went to a number of funerals, two which had no religion and plenty which had lots, and on the whole funerals with religion do better than ones without. If you take religion away, everyone is struggling to find a narrative line. I grew up in the Church of England with the King James Bible, and those words give you consolation whatever you believe.”

Because, if there is nothing one can do about death, if all one can do is, as Freud said, “make friends with the necessity of dying”, there is something about words which help, whether that’s the King James Bible, or Tolstoy, or Beckett (increasingly a reference point, McCrum says, as he gets older). “We’re storytelling people, aren’t we? We default to that mode when we’re making sense of otherwise chaotic data. A good actor can still a room of boisterous kids because they’ll be gripped by the music of the words. Words evoke memories and thoughts, put us in touch with ourselves, and that’s consoling.”

Since his stroke, McCrum has been fascinated by neuroscience. The brain is, he says, in terms of research medicine, “the dark side of the moon, the final frontier”. Its precise workings are still largely mysterious. He has held a human brain, he says, making his hands into a sphere about the size of a cantaloupe. It looks “blancmangey” and weighs about as much as a bag of flour.

“It’s an enthralling and mysterious subject and one which encourages a literary response because it raises very big existential questions about the nature of thought. In your head is all this porridgey stuff, and that translates into the Susan who is here, now, writing on a pad. We’re having an interaction which is entirely based on the electro-chemical movements of matter in our heads. Everything about you, your character, your spirit, your mind, imagination, memory, everything is all held in that space.”

And suddenly, we’re not talking about death anymore. We’re talking about the wonder of being alive.