Music review: Voice of the People, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh

Music review: Voice of the People, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh *****

Staged, along with the Sound House organisation, by Edinburgh University’s department of Celtic and Scottish Studies, in whose School of Scottish Studies Henderson was an early lecturer, the evening was MC’d by Gary West, piper and department chair of Scottish Ethnology, who described his one-time teacher as “one of the most important cultural figures to emerge in Scotland in the 20th century”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA sterling house band featured Alistair Paterson on keyboards, harpist Heather Downie, guitarist Innes Watson and fiddler-singer (and concert organiser) Lori Watson. Backed by them, Angus-bred singer-guitarist Steve Byrne got things off to a brisk start with one of the “muckle sangs”, Lang Johnny More.

Storyteller Essie Stewart delved back through millennia to Ossianic legend, while Gaelic actress and broadcaster Dolina MacLennan recalled first meeting Henderson in 1958 and read a tale of her own, about feuding pipers. Author James Robertson induced mass hilarity with four of his droll 365 stories and there was wit, too, filtered through mellifluously impenetrable Doric in Scott Gardiner’s singing of The Pirnie-Taed Loon. Piper and Gaelic singer Allan Macdonald delivered a song dating from the Napoleonic wars, with a vocal resonance that that seemed to emerge out of the earth, intoning in powerful unison with his small pipes.

Representing a younger generation of Gaelic singers, Mischa MacPherson gave poised voice to a song Henderson had recorded from Flora MacNeil of Barra, and was joined by West on pipes for some spirited puirt-à-beul.

Some of the evening’s outstanding moments, however, saluted Henderson’s own songwriting contributions to what he called “the carrying stream” of tradition. Findlay Napier delivered The John McLean March with stirring gusto while in contrast, Lori Watson stilled the house with The Ballad of the Speaking Heart, a heartbreaking fable of a mother’s love in the face of inhumanity, translated into Scots by Henderson from an old chanson populaire.

Alison McMorland, a long-time friend of Henderson’s (and whose usual duo partner, Geordie McIntyre, was indisposed) excelled with the potently life-affirming Flyting o’ Life and Daith, infusing its extraordinary, elemental dialogue with tension and, ultimately, triumph. She also gave affecting, swooping articulation to Love Song, Henderson’s heartfelt pean to Scotland written in the war-torn desert.

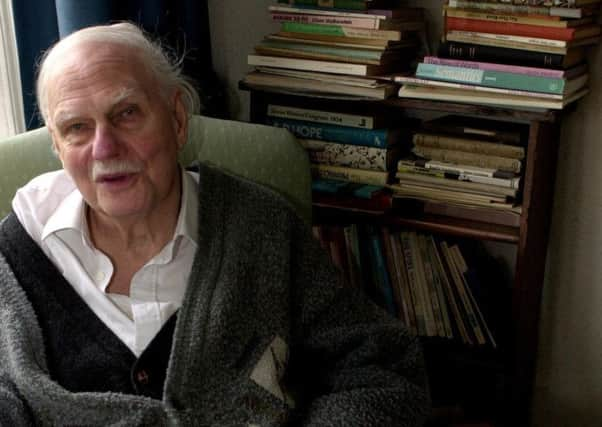

Yet another fine ballad singer, Fiona Hunter, pictured left, drew things towards a close with the inexorably unspooling tragedy of My Son David, one of the rich store of songs Henderson collected from the great traveller singer, Jeannie Robertson, before the obligatory ensemble finale with The Freedom Come-All-Ye, his eloquent Scots internationale, with added sections in Gaelic and German reflecting the breadth of the man’s cultural embrace. Jim Gilchrist