Jenni Murray: I was only journalist to silence Maggie Thatcher

Let’s try again. What about Mohammad Al-Annuri? OK, that’s harder. The subject of the earliest known painting from life of a Muslim in Britain. An ambassador from Morocco in London in 1600 to forge an anti-Spanish alliance. A big shot.

Before going into Jerry Brotton’s superlative talk on Saturday morning, I hadn’t heard of either. But they’re both, he showed, part of a huge story, one that shows that England’s past isn’t what we thought it was, and that its relations with the Islamic world were far more extensive and more amicable than most people realise.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdElizabethan England was, he stressed, a rogue state. After she was excommunicated by the Pope in 1570 – “a theological Brexit” – all Europe’s Catholics were encouraged to rise up against (and ideally kill) its heretic queen.

At Alcacer Quibir, the King of Portugal was killed and Elizabeth’s arch-enemy Phillip II of Spain took over the country and became even more powerful. So she approached the superpower at the other end of the Med. We both hate idolatory, she told Ottoman Sultan Murad. Let’s at least trade. All England had to offer were weapons, which the Turks then used on Catholic Europeans. “Arms for Iraq?” said Brotton. “We’ve been there before.”

That was only the start. England’s (not Scotland’s apparently) trade with the Islamic world was considerable, its knowledge of it spreading, its diplomatic links wide. And Mohammad Al-Annuri? The talk of the London steamie. Six months after he arrived, Shakespeare started writing Othello. This wasn’t a clash of civilisations, or Elizabethan England looking down on the Islamic world: Elizabethans were more knowledgeable – and politically weaker – than that. “Othello isn’t just about race,” said Brotton, “it’s more complicated. It’s about somebody who might save you – but might also cut your throat.”

Those links with the Islamic world stopped when James VI came to the throne and took England and Scotland back into Europe. But Brotton’s talk about the decades before than did just what a good book festival talk should do: slip into the mind like a turning key, opening up – or at least finding an echo – in other events in the process.

Queen Elizabeth I has long fascinated Jenni Murray and was one of the most obvious choices for her book A History of Britain in 21 Women. She knows exactly what she’d want to ask her. “Your father beheaded your mother. How did you deal with that?”

As ever, she had a good follow-up question. “Virgin Queen. Really?”

In an event that was the first to sell out at this year’s festival (it took all of 20 minutes), Murray showed that she’d done her research. If you’re ever in Westminster Abbey, check out how James VI got posthumous revenge on his mother’s behalf, shunting off Elizabeth’s tomb to lie atop that of her equally childless sister Mary, while reburying Mary Queen of Scots in the finest tomb imaginable.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnly one woman “terrified” Murray. In her interviews with Margaret Thatcher she knew she’d never got past the Iron Lady’s steely reserve. But after Thatcher lost power, she appeared on Woman’s Hour to promote her autobiography.

Finally, Murray summoned up the nerve to ask her what it was really like being the first woman Prime Minister, and brought up all of the things men had said about her, from Alan Clark’s sexist comments to Mitterrand’s “eyes of Caligula, mouth of Marilyn Monroe”. Silence. Nothing but dead air. Only later did she realise that Thatcher’s ever- loyal press secretary had never showed those quotes to his boss: they were new to her and she was taken aback. “So at least I can say I was the only journalist ever to have silenced Margaret Thatcher.”

Back, briefly, to Turkey – this time to modern Turkey, where Kurdish writer Burhan Sonmez talked about being interrogated as a 19 year old (“and in Turkey ‘interrogated’ means ‘tortured’”) and the civil war there in which 50,000 have died in the last 30 years and in which “if you say you support peaceful solutions that means you support terrorism and you’ll be put in prison”.

This event, in which he appeared with Deepak Unnikrishnan (born in Abu Dhabi to Indian parents, now teaching in the US) was another book festival gem. Both men write in a foreign language (Turkish in the case of Sonmez’s novel Istanbul, Istanbul, English for Unnikrishnan’s Temporary People); both turn to fiction to make sense of an absurd present. In the middle of Charlotte Square, we were suddenly among prisoners jogging in a completely dark Turkish cell, describing the city they imagine they are running through, or among Indian workers building high rises in the Emirates, a community almost without its old people, as when you lose your job you lose your right to live there.

It’s this kind of multiplicity of voice, said Zadie Smith, that she finds so energising about today’s fiction. Growing up in Willesden, when she asked about African writing she was told that “yes, there was one African writer and he was called Chinua Achebe”. Now, it’s so, so different and she almost wishes she was 15 again for that reason alone.

She doesn’t regret reading the classics she was taught at school, because if you don’t learn them then, you never will, and no one should ever take away Shakespeare from working-class children thinking they’re doing them a favour. But these days she is tiring of the judgments and moral quandaries of the 19th century novel (“As an older reader I find myself a little irritated with Austen”) and is set on discovering and searching out new voices.

For many of her readers, her own take on Willesden – where her latest novel, Swing Time, is also set – has provided a fair few of them. But although most people have focussed on issues of race and gender in her novels, she herself has always seen them as being more about class, where the absurdities of class-blindness fuel much of their comedy. Her next book, she revealed, will be a collection of short stories.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

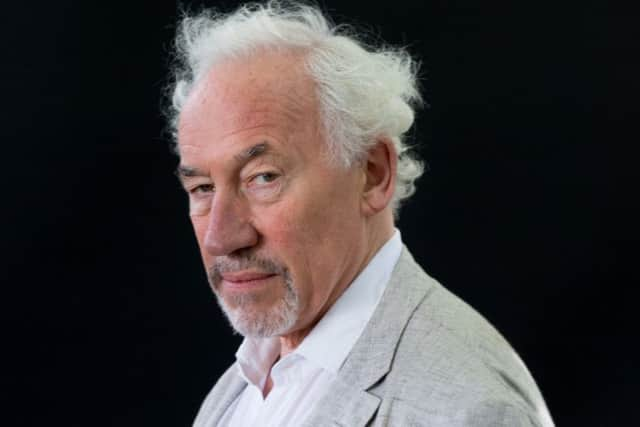

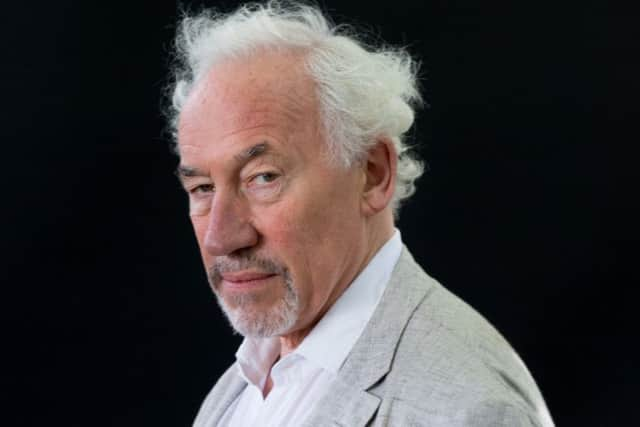

Hide AdEarlier, Simon Callow’s talk about Wagner was far more interesting on his theatricality than his music, but otherwise would have added little to the knowledge of even a half-convinced Wagnerian, especially as the event hardly allowed time for questions. There weren’t too many either in Roger Mc Gough’s event, but it didn’t matter. Since coming up to Edinburgh for the first time in 1962 (and sleeping, he revealed, for a couple of nights between the columns of the National Monument on Calton Hill) McGough has been a regular visitor. With Chris Riddell doing live drawings of his new poems – as lithe and witty as ever – as he read them out, he showed exactly why he’s always been such a welcome one.

He read from Summer with Monika – again, accompanied by Riddell’s illustrations from the new edition. The book first appeared, appropriately enough, during the Summer of Love 50 years ago, and time has added its own poignant cadences.

Marriage to Monika may turn out to be sometimes bitter and sometimes boring, but the hope and love of their first summer remains as magical and timeless as McGough himself.