How a small Scottish village faced the Great War

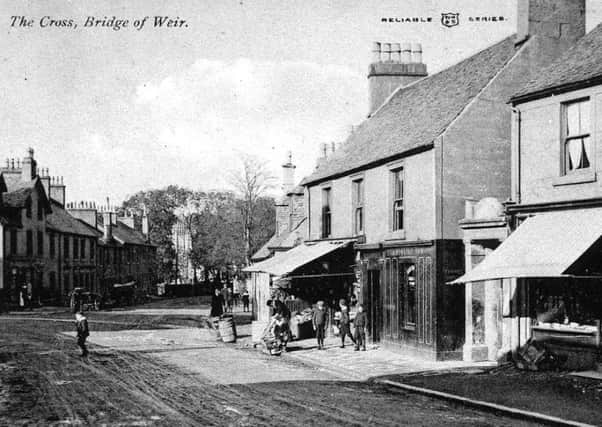

Supreme Sacrifice, A Small Village and the Great War, distills the devastation of the conflict through the village of Bridge of Weir in Renfrewshire.

While detailing the battles fought by its fathers, sons and brothers, the book also looks further afield to the political and military decisions that drew the men to battle and the efforts of their mothers and wives to keep them equipped with everything from socks and vests to ambulances and hospital beds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe book came about following a chance remark at the end of a church service in the village, when it was noted how little was known about the men whose names were marked on the war memorial.

Author Walter Reid, who worked on the book with Bridge of Weir residents Gordon Masterton and Paul Birch, said the book had become become “personal” and a “labour of love” as the stories of the village’s soldiers and families unravelled.

Reid, who has written several books on military history, said: “This book was quite different from writing an academic piece. You get involved in the personalities and the whole emotion. It is a different level from writing about grand military strategies and big, public personalities.”

The book breaks down the roles of the 72 village men who were thrown far and wide by the war, to Mesopotamia, Palestine, Salonika, the Italian Front, East Africa as well as the fields of France and Flanders.

The men are all remembered individually, from Private William Houston, of the Royal Engineers, a foreman with Renfrewshire County Council and church officer who died in 1918 after being exposed to mustard gas in 1918 to Private John Clark, of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, a stone mason who was killed at the Battle of Loos, whose body was never recovered.

At home, the book charts the “small committee of ladies who were so desirous of raising funds” to provide a bed named the “Bridge of Weir” in the Scottish section of the British Red Cross hospital in Paris.

Enough money was raised from the pulpits to buy two beds with an ambulance - “The Lass o’ Brig o’ Weir” - also purchased for the Western Front.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSocks, vests, gloves and purgarees - scarfs hung on the back of sun helmets - were regularly sent out.

The Supreme Sacrifice deftly weaves the tales of war with the tales of home, with hope sadly overshadowed by reality on many occasions.

The Barr family, who lived in one of the finer houses of Bridge of Weir, a prosperous village built around the railway to Glasgow, features heavily in the book.

Mary Barr, of Rockliff, was one of the women actively fundraising in the village and set to work collecting for soft drinks to send to the troops.

What is also learned of Mrs Barr, a widow, is that three of her four sons- Frederic, Lyle and Speirs - were all killed in action in less than a year,

The book said: “In pitifully rapid succession Mary Barr had lost her husband and three sons; she feared for her fourth. Her response was to throw herseld into raising money for the way effort.”

She did not survive the war and died on September 6 1918.

The Supreme Sacrifice also notes the village men who tried not to go to war, whether on practical or conscientious grounds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuguld Semple, a conscientious objector known locally as “The Simple Life” was from a notable family but rejected the comforts of home to live in a a wagon to indulge his love of nature and philosophy. He lectured locally on nutritious eating and food economy.

He refused to go to for his medical service and presented himself as a conscientious objector, with his cased backed at appeal by a local tannery owner.

Twice the panel granted him exemption on the grounds he continued lecturing. Semple travelled to London to lecture on food and returned home to marry a local woman, before leaving the wagon and moving into her vast villa in Kilmacolm.

The Armistice was marked in Bridge of Weir by the ringing of the school bell, with the rope breaking given it had not been used for so long.

It is estimated that up to 350 men from Bridge of Weir fought in the war, with the village working hard to return to normal as men returned, with businesses reopening and life’s ordinary routine resuming.

Reid said: “I think people were desperate to get back to normal. That is what they had been fighting for. These men fought so that freedom would exist.”

-The Supreme Sacrifice, A Small Village and the Great War, by Walter Reid, Paul Birch and Gordon Masterton is published by Birlinn.