Graham MacIndoe: Coming Clean | Adrian Wiszniewski: The Night Gardener | Robbie Bushe: Invasions and Excavations

Graham MacIndoe: Coming Clean Scottish National Portrait Gallery ****

Adrian Wiszniewski: The Night Gardener Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRobbie Bushe: Invasions and Excavations, Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh ****

For years, Scots-born photographer Graham MacIndoe said, he was in denial about having a drug problem. Then, one day he looked in the bathroom mirror and was shocked at what he saw: the grey skin and dead eyes of an addict. What is most interesting, however, is what he did next: he took out his phone and took a photograph.

It was the beginning of a long process of documenting his addiction, even as it overwhelmed his life (MacIndoe was eventually arrested for possession and sentenced to six months in New York’s infamous Riker’s Island jail; thanks, in part, to a drug rehabilitation programme he joined in prison, he has now been drug-free for seven years).

The 25 images in this show, which are now part of the SNPG collection, are an unflinching documentation of a life on the skids, but they also tell us that even when he no longer worked – when the commissions stopped and the equipment was sold to feed the drug habit – MacIndoe never stopped being a photographer.

NGS says the images are like nothing else in their collection. It is possible they are unique in the world of self-portraiture. Photographing other addicts felt voyeuristic, MacIndoe said, so he made himself his subject, and the pictures still have the rawness of the moments when they were taken, when nobody – least of all MacIndoe himself – knew if he would come out of this alive. In several of them, he has just injected, leaving a tell-tale trickle of blood down his arm. In others, he slips from consciousness, the camera – and by extension, we, the viewers – are his only witness.

These aspects of the show are shocking, but there is also depth and subtlety, particularly in the whole body of work viewed together. Annie Lyden, international photography curator at National Galleries, has worked with him to create a portrait of what addiction feels like, from the eyes-half-closed moment of seeming ecstasy as the drug takes hold to the stooped figure in the kitchen, overwhelmed by the tedium of the ordinary. The detritus of ordinary life is everywhere, here: the ironing board in the corner, the pale light from the television screen, and in one case, poignantly, a teddy bear bedspread. In all of them, MacIndoe is alone. In some, he doesn’t even appear, but the bathroom wall or the view over night-time Brooklyn only serve to enforce the sense of isolation.

The quality of the images is remarkable, especially given that most were taken on cheap digital cameras bought in pawn shops. Interestingly, the deeper MacIndoe slipped into addiction, the more concerned he became with the pictures he was taking, with light and the composition. In photographic terms, they are daring: his face lit in darkness by a single flame; and, in the strangest of them, he is framed against a window, the light behind him so strong it seems to shine through him, separating his head from his body. They are raw, uncomfortable, sometimes disturbing images, but they tell an important story, not just of disintegration but also of the capacity to recover.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn complete contrast to MacIndoe’s warts-and-all images is the approach in art which allows the imagination to run riot. Adrian Wiszniewski was one of the young figurative painters showcased in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art’s Vigorous Imagination show in 1987, and 30 years on, if this show of new work at the Open Eye is anything to go by, he is lacking neither in vigour nor imagination.

Wiszniewski has always been prolific and diverse. Over the years, he has designed rugs, made ceramics and written a novel (Touching Cloth, which was shortlisted for the Dundee International Book Prize). At one point, he announced he intended to give up painting; fortunately, he didn’t. In recent years, he has been painting with renewed force and skill. Dark backgrounds highlight a bright palette reminiscent of Matisse or Chagall, and evoke strange night-time worlds of trysts and fortune-tellers and vivid, exotic flowers.

Wiszniewski was always strong on line and this is a show as much about drawing as painting, at times conjuring the spirit of Alasdair Gray in the blending of mythologies, literary and personal. The best of the works here, like the large-format mixed media Lovers Consumed and the smaller Black Sea, are beautiful and strange and a little uncanny. Others, such as Spellbound in Rio II, are more jarring in colour and form, lacking the harmony of Lovers but, one suspects, still doing exactly what the artist wants them to do.

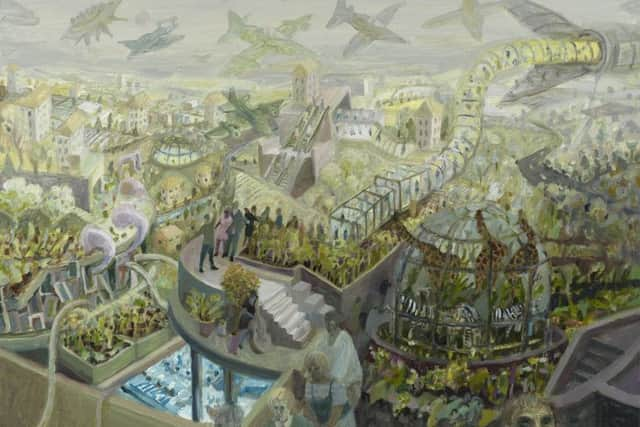

Robbie Bushe, who was named last year as the winner of the inaugural W Gordon Smith Award, is a near-contemporary of Wisniewski, and the paintings in his first exhibition at the Open Eye would sit well with the Vigorous Imagination artists. His blend of the surreal, the allegorical and the satirical, and his magpie eye, collaging images from art history, popular culture and his own subconscious, are reminiscent of Steven Campbell, in particular.

Bushe’s works are figurative, but usually feature large crowds, often on multiple levels, with a variety of dramas going on at once. Buildings open up, doll’s house-like, to reveal further stories within. Some are plays on words, like Self Storage. Others use architectural landmarks – the Forth Bridges, Edinburgh College of Art. Sections of the paintings use different dominant colours, helping to make them – while busy – pleasing to the eye. Immensely detailed, they layer surrealism with politics and black humour. In one painting, road signs give the distance in miles to “Disappointment” and “Bewilderment”.

Many of them feature walls and barriers, people struggling to get in or queuing to get out. All is grey on one side of New Hadrian’s Wall, while lush, green fields extend on the other. The Mexican Border, which predates Trump’s proposed wall but takes on fresh resonance in light of it, has shadowy figures patrolling the barrier between Mexico (colourful, free-form) and the United States (stilted, like an up-market restaurant depicted in shades of pink). At times, there is so much going on in a Bushe painting that one struggles to know where to look. Again, rather like Steven Campbell’s, each one presents a conundrum of ideas and narratives you suspect you will never solve; but you know it will be fun to try.

Graham MacIndoe until 5 November; Adrian Wiszniewski until 8 May; Robbie Bushe until 6 May