On this day in 1861: Edinburgh tenement collapse kills 35

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

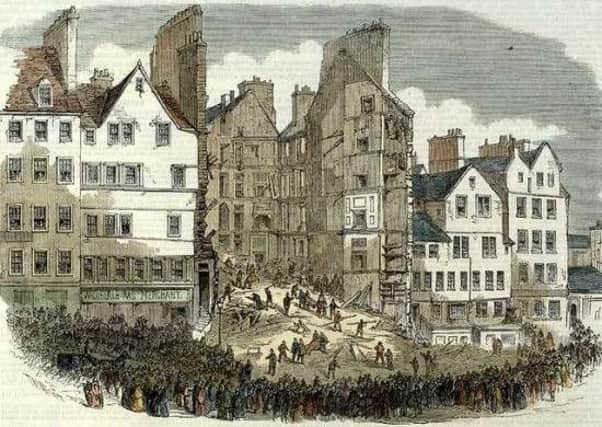

The tenement collapse and consequent loss of life in November 1861 was nothing short of catastrophic.

From 77 occupants, 35 perished during the collapse or died in hospital from their injuries. Coverage of the event made headlines nationwide, with the Scotsman newspaper of the time describing it as “one of the most calamitous and heartrending occurrences which it has ever been our duty to record”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe ancient seven-storey building which toppled that fateful night was located in the heart of Edinburgh’s densely-populated Old Town, on the north side of the High Street between Bailie Fyfe’s Close on the west and Paisley Close on the east.

Comprised mostly of timber, the tenement was thought to have been at least 250 years old at the time of the disaster. A façade of sturdy-looking, yet ancient, ashlar stone provided a false sense of security and belied the decayed state of the building’s interior.

Such dilapidation in 19th century Edinburgh was alarmingly common.

Poor living conditions

Living conditions in the Old Town were utterly appalling during the 1800s.

The population of the inner city had more than doubled from 82,560 at the turn of the century to 168,121 by 1861. Up to 15 families would often be crammed into a single tenement of up to 14 storeys high – some in windowless dwellings.

Many buildings had stood without any significant alterations for hundreds of years, and the sanitary conditions were infamously grim and filth-ridden. The threat of diseases such as cholera was huge, as access to clean drinking water was extremely limited.

An account from the Builders Journal of 1861 indicated just how vile certain areas of Edinburgh had become: ‘We devoutly believe that no smell in Europe or Asia can equal in depth and intensity, in concentration and power, the diabolical combination of sulphurated hydrogen we came upon one evening about ten o’clock in a place called Todrick’s Wynd.’ The sights and smells of nearby Bailie Fyfe’s Close, the location of the fateful collapse, would have followed much the same description.

Disaster

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnly hours prior to the collapse, a local shopkeeper had spotted cracks in the plasterwork and a depression in the roofline. A temporary prop was inserted in an attempt to prevent disaster. A case of too little, too late.

A little after one in the morning, two police officers on night duty had just finished attending a minor domestic incident in a close off the High Street when they witnessed an entire ‘land of houses’ fall to the ground in front of them with the most tremendous crash. A thick cloud of dust and debris shot up into the air as each level of the building collided with the street below.

Within minutes, scores of people, rudely awakened from their slumber by the almighty clatter, surrounded the disaster scene attempting to make sense of the catastrophe which had just occurred.

Curdled screams from victims trapped amongst the twisted ruins filled the cold, night air. Rescue workers battled through the night and well into the next day to extract bodies from the rubble. The death toll was exceptionally high - but there were survivors.

Heave awa’ lads

As dawn broke, the foot of a 15-year-old boy named John Geddes (some modern accounts describe the boy as 12-year-old Joseph McIvor) was spotted protruding from the debris. The youngster was wedged between a supporting beam and a mound of rubble, and is reported to have yelled “heave awa’ lads, ah’m no’ deid yet” as the rescue team worked frantically to saw through the beam and remove the debris.

A variation of Geddes’ spirited cry was carved into the lintel of the replacement building above Paisley Close, now known as ‘The Heave Awa’ Hoose’.

A chance meeting

One man named George Gunn had been spending an evening with friends in Stockbridge only to return home at exactly the moment of the catastrophe to find his family dead save for his youngest sister.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge was spared due to a chance meeting of an acquaintance outside his house - the brief chat stalling him at just the right time.

A total of seven children aged between 7 and 11 were also rescued without injuries. Children who lost both parents were sent to the City Workhouse.

The search for survivors uncovered a large number of mutilated corpses in the days that followed, with the death toll eventually reaching 35, including many young children and infants.

As a footnote, The Scotsman report of the disaster mentions that “the influx of prisoners to the Police Office, which on Saturday nights and Sunday mornings is generally very great totally ceased, the most of that class of people having evidently repaired to and remained at the scene of the disaster”.

The City Improvement Act of 1867

The appallingly tragic events which took place at Bailie Fyfe’s Close turned out to be the bitter tonic for change which Edinburgh’s authorities needed. Cholera epidemics were killing thousands in the less salubrious areas, and the city centre tenement collapse was the final straw.

Charles Dickens, a frequent visitor to the capital, once stated that he saw more poverty and sickness in the course of an hour’s stroll through the Old Town ‘than people would believe in, in a life’. Dickens was in Edinburgh at the time of the collapse and is said to have been very much in favour of swift action being taken to tackle the city’s dreadful housing and sanitation problems.

The poor victims of the 24th of November 1861 were martyrs for change in Edinburgh. The City Improvement Act was passed by Lord Provost William Chambers in 1867, and towards the close of the 19th century a vast extent of the Old Town’s ramshackle stock of medieval housing had disappeared. John Knox House, dating back to the 1470s, is a rare and notable survivor.

DOWNLOAD THE EDINBURGH EVENING NEWS APP ON ITUNES OR GOOGLE PLAY