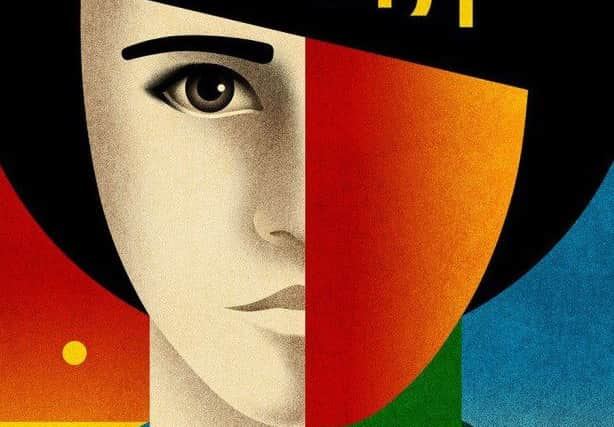

Book review: The Vanishing Futurist by Charlotte Hobson

The Vanishing Futurist by Charlotte Hobson | Faber & Faber, £16.99

She becomes romantically embroiled with Nikita Slavkin: the “vanishing futurist” of the novel’s title. He is the leader of the group, the brains behind the bizarre operation and the man who ultimately extracts himself from a relationship with Gerty by enforcing celibacy on his comrades, purportedly so that they can devote themselves to the commune.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe story is told to us by an elderly Gerty, who has returned to England decades earlier. “As I write this, I am not far from eighty myself,” she explains. Her faded memory of her time in Russia is augmented by props: boxes from the attic containing old newspapers, scents and information which “dredge Slavkin’s story up from its decades of silence”.

She is writing to tell her daughter, Sophy, the truth, she reveals. But what is the truth? What is the secret that she and her husband, Paul, have kept for all these years?

This first novel by Edinburgh University graduate Charlotte Hobson, who began her writing career when she penned an award-winning travel book about her year abroad in a remote Russian town amid the collapse of communism, delves deep into the complex Russian psyche of the period.

The tale ping-pongs between the conservative – the respectable elderly English lady living in her London flat – and the absurd, and the style has shades of Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master And Margarita. Meanwhile Slavkin’s invention of the PropMash – an “immunisation” chamber to anything capitalist – is reminiscent of Anthony Burgess’s Ludovico technique in A Clockwork Orange.

We find that amid the absurdity of the situation – a mishmash of brainwashing, idealism and romantic love – even Gerty is not a reliable narrator: “If this account is to be worthwhile at all, it seems to me, it must be as honest as I can manage,” she writes, explaining that there are “balled up” pieces of paper on the floor of her Hackney flat as she repeatedly fails to give a true description of events.

What is clear, however, is that this is a very accomplished first novel.