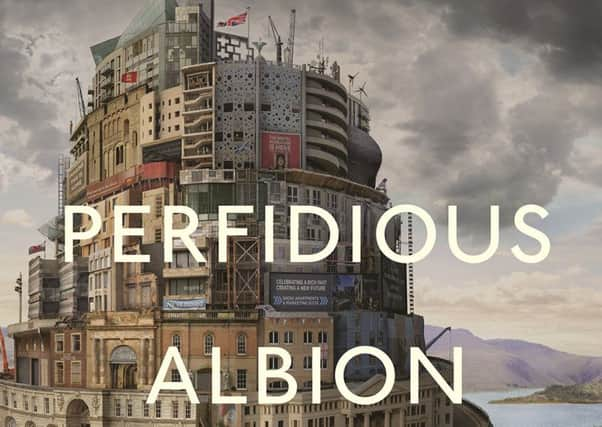

Book review: Perfidious Albion by Sam Byers

It is set in the not-as-fictional-as-it- sounds Edmundsbury, a place where nothing happens: until it does. Robert Townsend is the kind of man who thinks he is a good guy, especially when launching a journalistic crusade on behalf of Alfred Darkin, an aging widower whom local developers (sneakily called “Downton”) are trying to “relocate”. Darkin’s favourite columnist is a right-wing politician, Hugo Bennington, leader of the slightly sagging “England Always” party. One of Darkin’s neighbours is a black woman, Trina James, working in the local tech company and data-gathering operation, Green. She eventually intersects with Jess Ellis, who is an academic as well as being Townsend’s partner.

You can already see how the gears and wheels within wheels will work. Not well, given the emergence of The Griefers; masked individuals who stage a Situationist happening where they claim they will reveal everyone’s internet history unless one person voluntarily “submits”, with the catchphrases “We Are Your Face” and “What Don’t You Want To Share?” As a counterpoint to them there is the thuggish “Brute Force” group, with whom Bennington is negotiating a fractious entente cordiale while simultaneously wooing the Downton executives.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGiven that Bennington is a beer-swilling, chain-smoking opportunist whose vision of England is less spinsters cycling to chapel and more about not liking anyone not white, it is easy to see why this has been branded as a post-Brexit dystopia. In a way, that’s utter tosh; though of course these themes thread through the novel. It is, above all, a comic novel. In fact I would be very surprised indeed if it did not make it on to the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse shortlist for comic fiction – Bennington seems very much an heir to PG Wodehouse’s Roderick Spode, leader of the Black Shorts, who first appears in The Code Of The Woosters. But there is more than just a resemblance on account of uppity right-wing lunatics. One of the grammars of comic writing is quite simple. A problem arises. The attempt to solve the problem creates deeper problems. Those trying to wriggle out of a mess of their own making get a comeuppance. The messes here are almost always digital.

Townsend is being trolled online by “Julia Benjamin”. Jess operates multiple online identities as a way of getting back at herself having been trolled by a “men’s rights” academic. Trina is working on a project about incentivising workers with few or any rights, and gets in trouble because she tweeted a comment about Bennington with the hashtag #whitemalegenocide. As for Bennington – that would be giving away one of the best laughs in the book. The key point is that everyone is never just themselves, but also their personae, their avatars, their disguises. At one point Robert observes to his pleasingly two-dimensional boss, “there’s a big difference between an allegorical bomb and a real one”, only to be rebuked with the chilling phrase, “To us, Robert, the allegorical bomb is the real bomb, and the real bomb is just an allegory.” This is post-truth taken to the next level. The same character gives the sage and sadistic advice, “You’re nobody until somebody hates you.” The toxic nature of the virtual has rarely been more satisfyingly skewered.

In this hall of mirrors, some aspects of the dreadfulness of the real come through. Almost all of the men are charlatans and chancers. Most of the women are no better, but at least they realise that the “blankness of whatever reality remained when life’s deceptive overlay was removed” is a kind of freedom. (“Nothing meant anything” thinks one character, a kind of existentialist koan).

The comedy is of that dark nature where language begins to buckle. One of the “Brute Force” enforcers, sent to “take care of” the unappealing and pitiable Darkin, informs him he is worried “a load of people” might come round here “wanting to do a genocide”. The placing of that “a” is perfect. He clearly doesn’t know what “genocide” even means, except that it is a lightning-rod to galvanise resentment.

Towards the end, we get the true horror of the situation. “You think we can do this kind of research on lab rats?… There’s nothing more to be learned from electrocuting rodents in mazes.” In the days of revelations about Cambridge Analytica, Byers’ novel could hardly have greater resonance. Yet, as with all comic fiction, happenstance leads to reckoning. Life, unfortunately, is not comic fiction.

Perfidious Albion, by Sam Byers, Faber & Faber, £15.99. Sam Byers is at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 21 August