Book review: People, Places And Piazzas: The Life And Art Of Charles Mackie

This sense of Mackie’s relative neglect explains the author’s determination, inspired by a picture in her childhood home, to resurrect his reputation. She is right, too, to say that he has been a victim of our unbalanced view of late 19th century painting in Scotland. The clamour about the Glasgow Boys has crowded out painters not easily adopted into their narrative. Arthur Melville, for instance, although an east coast artist, has simply and ruthlessly been co-opted as a Glasgow Boy. Mackie was a similar figure. He was friendly with the Glasgow painters, particularly with Hornel, but he has never been co-opted in this way and in consequence has been neglected. Like Melville, too, however, he was a brilliant artist whose advanced ideas set him apart from his contemporaries. He was, for instance, the only British painter to be in close touch with the Nabis, artists like Serusier, Bonnard and Vuillard in France. Reflecting the influence of Gauguin, from the Nabis he learnt radical new ideas about the emotional power of colour. Clark describes both how deeply this affected him and how brilliantly these ideas were interpreted in his best work.

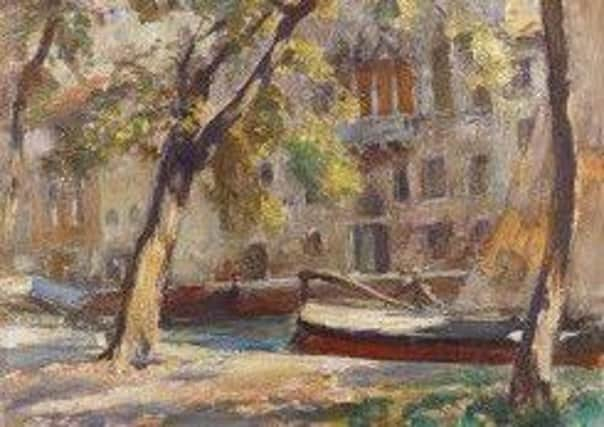

Mackie has been unlucky, however. Some of his largest and most important work has been lost or destroyed. Only a fraction remains, for instance, of a major decorative scheme that he painted for Patrick Geddes in Geddes’s home in Edinburgh’s Ramsay Garden. The survivors of this scheme, however, would have looked quite at home beside the contemporary work of Bonnard or Vuillard. Later, Mackie brought the same highly original way of designing with colour to a major series of woodblock prints. Inspired jointly by Gauguin’s use of the medium and by Japanese prints, they were much admired and are now the most accessible part of his legacy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe author also recounts Mackie’s close involvement with art in Scotland, with Geddes, with the Society of Scottish Artists and with the Scottish Modern Artists’ Association. This latter was set up to establish a collection of contemporary Scottish art, but the author seems to think the wonderful collection that resulted went to the National Gallery. Scandalously, however, although offered to the nation, apart from a tiny handful of pictures the offer was rejected. It went to Edinburgh City Art Centre instead.

Clark’s enthusiasm is infectious. As she is avowedly not an art historian, however, the book could perhaps have been edited more closely. Nor is her language always felicitous. Writing about the artist’s son Donald’s memories of Venice, for instance, she writes, “[his] strongest reminiscence was of seeing a female nude in the flesh. Though the experience was over 50 years distant, he was able to recall a lot of detail.”

The structure of the book is a slightly unresolved mix of topics and chronology which can be confusing. It ends with the end of his life, but doesn’t begin with the beginning and you suddenly come upon his early life in chapter five. Also, although the publishers have done a great job bringing out titles on neglected Scottish artists, the production values in this case don’t do justice to the subject.

Nevertheless, in spite of such reservations, this book does what the author intended and recovers for us the life and work of a too long neglected artist.

*People, Places And Piazzas: The Life And Art Of Charles Mackie, by Pat Clark, Sansom & Co, £25