Book review: The Day Of The Mountain by Timothy Neat

The Day Of The Mountain by Timothy Neat

Born in 1943, he originally set out to study art. “As a boy and at school,” he says, “I drew and painted a good deal. At university – studying fine art – I got put off the practice of both almost for life.” He took up drawing again – although so far not yet painting – in 2011. Since then he has drawn incessantly, filling 24 sketch books, all the same handsome Venetian volumes, with some 3,000 drawings, all in pen, ink and wash. It is a volcanic output and not just in volume. It looks it too. With energy exploding off the page, his dramatic line in pen or brush and dark clouds of wash are together like lightning in the smoke of an eruption.

His drawings, though diverse in appearance, are mostly of people – portraits, figures in action, nudes, seen, remembered or imagined – but there are also occasional smoky landscapes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe uses his medium in a way that reminds me of Goya. Goya at his more benign, however, for there is warmth and engagement with humanity throughout this remarkable output.

Locked away in a pile of sketchbooks, these drawings might have remained unseen, but prompted by his friend, the great commentator on art, John Berger, a selection of more than 300 has been brought together, not in an exhibition, but in this book.

The Day Of The Mountain is divided into nine chapters, each with a title and a postscript. The individual drawings, however, though numbered, are not captioned on the page, but only in an index. You enjoy the drawing first and then, made curious, seek the title.

Berger has contributed a foreword. So too has the Canadian poet Ann Michaels, who has also contributed a poem, “Somewhere Night Is Falling”, a verbal caesura in the flow of visual images.

In his foreword, Berger describes Neat’s drawings as Dantesque and in conclusion says: “Just as the cinema records events using 24 frames a second, Tim Neat depicts life by assembling the energy of multiple lifetimes on a single page. And we turn the pages.”

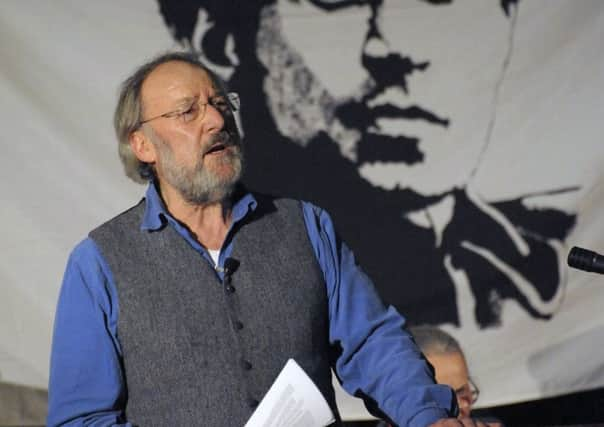

But speaking at the launch of his book in Edinburgh last month, Neat reminded us how elsewhere, Berger also described life itself as like a roll of film, how, “when he comes to the end, man discovers that he carries, stuck there on his back, the entire roll of the life he has led”.

This remarkable book, or rather this portable exhibition, has been published in a small edition, partly by subscription. Consequently it is expensive, or may seem so, but its interest will endure and it is worth every penny.