Book review: An Artist's War, by Phyllida Shaw

Alice and Morris Meredith Williams were artists who, working both together and separately, but also frequently in partnership with the prolific Scottish architect and designer Sir Robert Lorimer, left a remarkable legacy in several of Scotland’s most important monuments just after the First World War.

Most notable was the National War Memorial in Edinburgh Castle where Alice was the lead sculptor. There, among more than a dozen individual works, most impressive is the great bronze frieze in the Shrine, a procession of all the ranks of all the services together with their equipment. Typical of much that they did, this was a joint work. Alice, the sculptor, modelled the figures. Morris designed the panels and drew the full-sized cartoons from which she worked.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

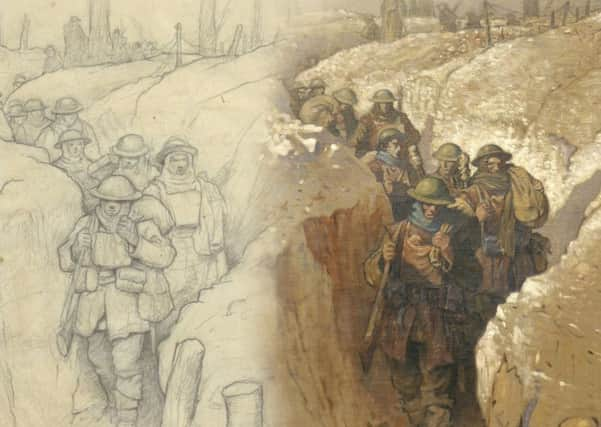

Hide AdMorris’s special qualification for this extraordinary sculpted document was his experience of the war. Throughout his period of service, from 1916-19, he recorded what he saw in precise and closely observed sketchbooks and also in paintings, though opportunities to paint were limited.

Though some of the work they did postwar has been covered in various publications, no comprehensive account of it has been given before and Morris’s war drawings have never been published. Now the work of both husband and wife is covered by Phyllida Shaw in the beautiful and informative book, An Artist’s War: The Art And Letters Of Morris And Alice Meredith Williams. The main part of the volume is in effect also a partnership between Morris and Alice, though posthumous. Combining the letters they exchanged, sometimes almost daily, and his remarkable drawings and paintings, it is a unique diary of the war.

The couple had both trained as artists in Liverpool. (Morris was three-quarters Welsh and Alice’s family name was also Williams.) They met as students in Paris and were married when Morris was appointed art master at Fettes, taking up his post in 1905. Both continued to work and to exhibit regularly until the outbreak of war. Morris, although already in his mid-thirties, was keen to join up, but was rejected initially as too short. In 1916, however, when the first Bantam regiments were formed of men who didn’t reach the standard minimum of 5’3”, he was given a commission in the 17th Battalion, the Welsh Regiment. He served at the front, later he made maps, and finally, and most congenially, he designed camouflage.

Throughout the war he recorded what he saw and 15 sketchbooks survive. He was a fine draughtsman and his drawings are a fascinating record giving all sorts of insights into the war as it was experienced. However, his paintings, always informed by his drawings, also show that he was not merely a reporter, but a considerable artist. He admired Frank Brangwyn and that connection perhaps best locates him artistically, but he had his own vision and the results can be very striking, as in The Dugout or the Millet-like Woman Child.

The second and shorter part of the book gives an account of the work the couple did after the war, both as partners and individually. The last chapter is an account of Morris’s individual career as an artist. At the end of the war, he was kept on by the army to make paintings of record. Alice, who had passed the war in the south, was commissioned to do a series of painted plaster models of women’s war work for the newly founded Imperial War Museum. When the couple returned to Edinburgh in 1919 and Morris took up his post at Fettes again, they both worked with Sir Robert Lorimer in a number of places. She designed a major bronze group for Paisley War Memorial, for instance. Both artists also worked for Lorimer in St John’s in Perth and in St Peter’s in Falcon Avenue, Edinburgh. She and Morris together designed a set of reliefs for the war memorial Lorimer designed for Queenstown in South Africa. For the same memorial she also modelled a monumental bronze figure of St George, very like the one she designed for the Scottish National War Memorial. Together the couple also designed stained glass and carved and painted altarpieces. One very striking example was a carved and painted altarpiece for St James the Less, Penicuik, designed by Alice on her own.

Quite soon after the completion of the National War Memorial, however, Alice was diagnosed with cancer and the couple left Edinburgh. She died shortly afterwards in 1933. Morris, who lived on till 1973, continued to design glass. He also produced paintings, drawings and book illustrations. Some are striking, but his most touching work is a painting of Alice, half-hidden under a parasol, done in Paris in 1904 at the beginning of their remarkable relationship.

*An Artist’s War: The Art And Letters Of Morris And Alice Meredith Williams, by Phyllida Shaw, The History Press, £30