Art reviews: The View From Here | Alexander Nasmyth: His Family and Influence

The View From Here: Landscape Photography From the National Galleries of Scotland ****

Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

Alexander Nasmyth: His Family and Influence ****

Fine Art Society, Edinburgh

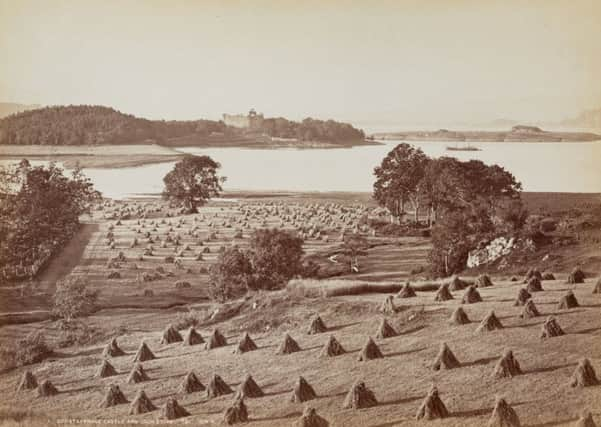

The national photography collection, only established in recent years, is already a major resource. The creation of a dedicated photography gallery in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery has also made it accessible in a way that it never was before. The latest show from this photographic treasure trove is devoted to landscape, a subject for photographers from the very first and one which has had a central place in Scotland’s self image. Already in the 1860s the superb photographs of Scottish scenery by rivals George Washington Wilson and James Valentine were in mass circulation as postcards and cartes de visite. Pioneers in taking photography out into the field, they were both hugely productive. The archive of Wilson’s work in Aberdeen University numbers more than 40,000 negatives. Rivalled closely by Valentine in Dundee, he became one of the largest producers of photographic postcards in the world, spreading the romance of Scottish scenery far and wide. Nor was this a Victorian curiosity. Valentine, for instance, set up as a photographer in Dundee in 1851 and it was only in 1967 that his company stopped producing monochrome postcards from his original negatives. One can only guess at the impact that the circulation of images like his Falls of E’e at Strathaven, or Washington Wilson’s pictures of Killiecrankie (the latter seen here in carte de visite form) or his Approach to the Quirang, must have had as witnesses worldwide to the “reality” of the romance of Scottish scenery.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe story begins here with Hill and Adamson, however. Although best known for their portraits, Hill was primarily a landscape painter, so not surprisingly, the partnership also produced some beautiful landscape pictures. A Fence and Trees at Colinton, for instance, with the light shining through a tangle of branches and sparkling on the leaves is a romantic landscape to match any painting. The print and paper negatives of a tree shown together also reveal the magic of the calotype process by which such images were made.

It was not long before improved technology allowed photographers like Wilson and Valentine to travel in search of subjects. Amateurs like John Muir Wood, for instance, also travelled to find subjects. A photo of basalt columns that he took in Northern Ireland is also testament to the increasing importance of photography to science. Photos taken of historic places were and still are invaluable. Most impressive of all the photos for sheer grandeur here, for instance, are Francis Frith’s photographs of the Pyramids in Egypt. Made in the 1850s he used huge glass plates to match the magnificence of his subject and in this he succeeded. His pictures have a clarity and almost physical spaciousness that no modern technology can match.

Nor indeed could painting. With images like this, photography is manifestly its own art. Nevertheless, its relationship to painting and its status as an art remained uneasy. Photographers formed societies to give respectability to their art. They also explored new, more “artistic” techniques. Photogravure, for instance, was developed as a way of turning a photograph into an intaglio print to emulate traditional print forms and claim artistic status accordingly. Not in vain either. Peter Henry Emerson’s Misty Morning at Norwich is a beautiful example. Both the image of boats on calm water and the subtle simplification of tone that photogravure achieves are like a contemporary impressionist painting. To judge by examples here, however, the Bromoil transfer process, another way in which photography set out to imitate painting, was not a success.

Indeed, generally this show suggests that new technology doesn’t necessarily improve quality. As the story unfolds into the 20th and 21st centuries, the beautiful Hebridean work of Paul Strand, for instance, like Bill Brandt’s majestic picture of Hadrian’s Wall, echo the rich black and white tonality of their Victorian predecessors. Fay Godwin achieves something of this too. Outstanding in any such company though is Thomas Joshua Cooper who actually uses a Victorian plate camera. The example here is of the River Devon at Rumbling Bridge. Beside such a rich and suggestive image, Michael Reisch’s large Landscape ,7/001, an overtly modern work, seems a little thin. It claims to be a computer generated highland landscape, but actually matches in detail George Washington Wilson’s Approach to the Quirang. Ironically, as Reisch’s picture was made to celebrate Telford’s 250th anniversary, the only intervention seems to have been to erase Telford’s road around the base of the mountain. This seems to contradict the claim of the label that Reisch’s photo “challenges the very basis of photography as a medium for recording the veracity of the world.” Indeed, we learn from its label in turn that Alfred G Buckham’s famous aerial photo of Edinburgh made around 1920 is a composite several different negatives and so is every bit as much a “made” image, or a challenge to photographic veracity as Reisch’s picture.

The pioneering photographers of the Scottish landscape here were working in a tradition of imagery already well established in both painting and poetry. David Wilkie called his friend Alexander Nasmyth “the father of Scottish landscape”, but it was a tradition that reached back into the 18th century before either Nasmyth or indeed Walter Scott, the ultimate inspiration for all those sepia postcards. If what Wilkie claimed for his friend wasn’t strictly true therefore, nevertheless, Nasmyth as well as teaching or influencing a whole generation of artists, was also actual father to a large family of landscape painters. This is the cue for a delightful exhibition at the Fine Art Society, Alexander Nasmyth - His Family and Influence. The show includes a lot of fine work by Nasmyth himself. A beautiful painting of Armondell Bridge, for instance. He was a man of many talents, however. Almondell is also one of several bridges he designed. With a very wide flat central arch, it bears witness to his skill as an engineer. A big painting of Loch Fyne likewise testifies to his work as landscape architect for the Duke of Argyll. His son James inherited his technical interests and became a distinguished engineer, though a beautifully painted fantasy, Castle Forlorne, shows he was also no mean painter. It was his brother Patrick who became the best known painter among the children, however. He worked mainly in England in a manner that combined beautifully his father’s inspiration with that of Dutch painters like Hobbema and Ruisdael.

It is a shame that Alexander’s six daughters, all painters, are not better represented. It may be that they worked so closely with their father and on his paintings too that their work has become indistinguishable from his. Certainly works attributable to his daughters are rare, but perhaps it is the case that works we say are by Alexander are actually by him and/or either Jane, Barbara, Margaret, Elizabeth, Anne, or Charlotte. Two small works by Jane, however, and a copy of Andrew Geddes’s portrait of their father by an unnamed sister show how their talents could also flourish independently.

The Nasmyth household was a magnet for younger painters and Alexander’s influence among them was very considerable, both with those who were in close contact with him like Wilkie himself and Andrew Wilson, for instance, and at a greater distance Reverend John Thomson of Duddingston and David Roberts and Horatio McCulloch, all of whom are included in this show. n

*The View From Here until 30 April 2017; Alexander Nasmyth until 12 November