Art reviews: Linda McCartney at Kelvingrove | Patrick Staff at DCA

Linda McCartney Retrospective, Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum ***

Patrick Staff: The Prince of Homburg, DCA ***

McCartney’s early work often involved photographing musicians: Eric Clapton, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin. She photographed the Rolling Stones during their American tour of 1966, and was the first woman photographer to shoot a cover for Rolling Stone magazine. She came to the UK in 1967 with the aim of photographing the Beatles and the rest, as they say, is history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, what greets us first in Kelvingrove’s rather labyrinthine exhibition space is not a rogues’ gallery of rock legends but a collection of images of Linda herself: Linda by Paul, Linda by Eric Clapton, Linda by Jim Morrison, Linda by Linda. Of course, McCartney’s personal life became, quickly, more famous than her professional one, but she was interested in her own image too. One suspects that, were she alive today, she would be the queen of selfies.

By the time the Beatles were making the White Album she was often in the studio, and her candid shots of the band working and hanging out will be a must-see for Fab Four fans. After the break-up of the band, as life became focused on family, photographs of Paul and the children predominate. After they bought High Park Farm on the Mull of Kintyre, there is a Scottish tone to much of the work.

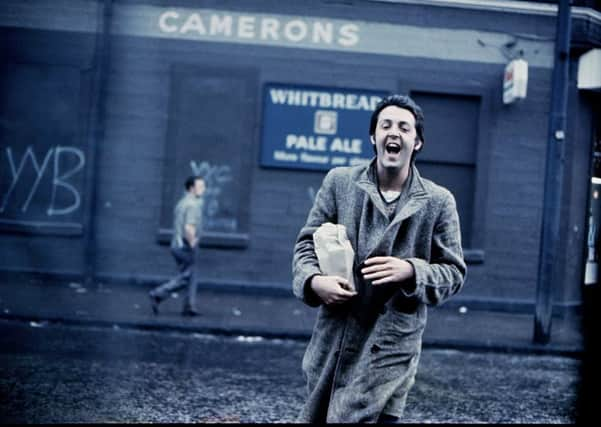

So, we have Paul in the bath, Paul with Martha the old English sheepdog, Paul diving into a swimming pool (shot from below – I’m still trying to figure out how she did this without ruining her camera), Paul tightroping along a fence, naked Paul with baby Mary, Paul with the children at various different stages of development. These were more than snapshots: several books of Linda’s photographs of the family were published, and they also appeared on record sleeves. The family album was a key part of how McCartney defined his brand as a musician, and the couple were keenly aware of the power of the right kind of image, more than 30 years before social media existed.

After yet another wall of Paul, one craves variety. Some of McCartney’s observational photographs are her most interesting: there’s an exquisite black and white image of horses in snow, a landscape reflected in a glass teapot, a tiny moment of drama with two men on a train, two women sharing a bicycle in Portugal. There are portraits of old men in Campbeltown and thoughtful images of Allan Ginsberg, Gilbert & George and Jim Jarmusch.

McCartney knew how to look for an interesting angle, such as shooting a subject in a car’s rear view mirror. She also experimented with photographic technology, both from the past, such as the cyanotype, and with new, evolving technologies: her Polaroids have great immediacy, though they have dated more than most of the other work. These form intriguing interludes between the family pictures, but the balance suggests that the latter is by far the biggest body of work in the collection.

Meanwhile, DCA is hosting the largest exhibition to date by British contemporary artist Patrick Staff. As the title suggests, the show draws deeply on Heinrich Von Kleist’s 1810 play, The Prince of Homburg, with the central piece of work a 23-minute film which adapts aspects of the play to create a psychedelic, postmodern documentary on trans rights.

Von Kleist’s play, about a professional soldier in the 17th century who is sentenced to death for disobeying orders, is sometimes said to be a paean to law and authority (it was very popular during the Third Reich), but could also be said to question authority and champion free will.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome adaptations play it as a tragedy, with the Prince executed at the end, others as a kind of comedy, in which he is pardoned. One French production even invited the audience to discuss how the play should end. In the text, the whole nature of reality seems uncertain: the play begins with the prince sleep-walking, and ends with him being told the events have all been a dream.

In the midst of this shifting, fluid narrative, Staff finds a place to ask questions which pick up on themes of law, freedom, imprisonment and defying boundaries. The exhibition sets up a dichotomy between night and day, light and dark, the ordered, rational, restrictive world and the one of dreams, subversion, creativity, the unconscious. The film, shown in a blacked-out space with red walls and cabaret-style tables and chairs, cuts between collaged footage, abstract painting on 16mm film and interviews with academics, activists and trans performers.

The other gallery – in bright daylight – shows a series of photograms: resonant objects “photographed” with light. Aluminium fencing, like that which might top a security fence at a prison or a palace, runs through both rooms, with objects and clothing impaled on it.

Staff’s implication, perhaps, is that the stance of the trans individual in society is, like that of the Prince of Homburg, a political position. Both share a sense of weariness at how things are: days before the exhibition opened, the Scottish Parliament postponed its plans to update Scotland’s gender recognition laws. But one response to that weariness is creativity, to carve out a space, to imagine other ways of being.

This work, then, is the response, taking Von Kleist’s ideas and dragging them forcibly into a world which is determinedly postmodern. If the whole thing feels imprecise, it is at least filled with the energy of Staff’s own style and vision.

Perhaps this is the point: not to make the questions clearer, but to complicate them further in interesting ways. - Susan Mansfield

Linda McCartney until 12 January; Patrick Staff until 1 September