Art reviews: The Italian Connection | Modern: 20th Century Art and Design | John Byrne

The Italian Connection, City Art Centre, Edinburgh ****

Modern: 20th Century Art and Design, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh ****

John Byrne: Then Till Now, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2016, Scotland’s emphatic vote to remain in the European Union was in keeping with our history. We are an outward looking nation. There have constantly been Scots living and working throughout Europe and this has been as true of our artists as any other profession, though for the artists, Italy was usually the preferred destination. Already in the eighth century, the Pictish artist who made the great St Andrews Sarcophagus had surely seen the grandeur of Rome. In the 18th century, a sojourn in Italy, often for years at a time, was a must for any aspiring Scottish artist. This continued for much of the 19th century and in the 20th, when Edinburgh College of Art received the munificent Andrew Grant Bequest, the first priority was to set up travelling scholarships and many of those who won them still chose to go to Italy.

Imaginatively, in its new exhibition The Italian Connection Edinburgh’s City Art Centre has drawn on its own rich collections of Scottish art to illustrate something of this story. The earliest work is Allan Ramsay’s charming portrait of Katherine Hall of Dunglass, painted in 1736 when the young Ramsay first set up his studio in Edinburgh. His father remarked on the many “young beautys” (sic) to be seen there and Katherine Hall is clearly one of them. The look in her eye, however, and her encouraging half smile, both so beautifully observed, suggest that the handsome young painter may have been part of what drew them — but then she is painted as the chaste goddess Diana. In fact this lovely portrait was painted just before Ramsay made his first trip to Italy, but as he eventually made four visits and died on the return journey from his last, he does personify the theme of the show. William Mosman was also in Italy in the 1730s and like Ramsay studied in Rome in the studio of Francesco Imperiali.

Mosman’s portrait of James Stuart, later Lord Provost of Edinburgh, painted in 1740 just after the painter’s return to Scotland, shows admirably the Italian elegance he had learnt from his teacher. Later in the century, David Allan spent more than ten years in Italy, mostly between Rome and Naples. When church decoration was still a bit risqué, he brought a little of Italy to the Episcopalian chapel in Roxburgh Place with paintings of Faith, Hope and Charity. Charity here represents this trio.

The show demonstrates the undoubted strength of the City Art Centre’s collection but it does also show up one or two gaps. I was surprised to realise that Jacob More is one of them. Known simply as More of Rome, he really personified the theme of the show. He was resident in Rome when Henry Raeburn and Alexander Nasmyth stayed in the city in the early 1780s and his limpid landscapes may well have influenced Nasmyth’s own approach. Nasmyth had been a studio assistant to Ramsay who was then also in the city on his last visit, so, through Nasmyth, there is a likely link in Rome between the older painter and Raeburn, his young successor.

Raeburn’s Sir James Stirling is a classic male portrait, but the sitter’s pose mirrors exactly – it is reversed – Velazquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X that Raeburn saw in Rome and drew inspiration from for the rest of his life. The city does have a couple of very fine paintings of Edinburgh by Nasmyth (and used to have a third that a former Lord Provost gifted to the Queen.) So it is a shame he is only represented here by a small watercolour of the city. Nasmyth’s pupil Andrew Wilson later became a long term resident in Italy, but as an enterprising dealer he had earlier managed to come and go during the Napoleonic wars. Here a luminous small sketch of Edinburgh shows the Mound under construction. In Edinburgh, Wilson was Master of the Trustees Academy. Among others he taught Robert Scott Lauder who, no doubt encouraged by his teacher, spent five years in Italy. A superb portrait of his father, John Lauder of Silvermills, evidently predates this sojourn, but shows the promise that the trip would help realise.

Thereafter there seems to be a bit of a hiatus which reflects the collection rather than fashion – Italy never did go out of fashion, but the story resumes with a splendid sunset view of Venice by Pollok Sinclair Nisbet. Painted in 1875, as Venice dissolves in the pink light of the setting sun, the painting seems to stand exactly between Turner and Monet. Art history never is as simple as it is made out to be. Master printer Muirhead Bone spent two years in Italy before the First World War. A spectacular etching, Rainy Night in Rome, shows he didn’t waste his time. At exactly the same moment, FCB Cadell made a visit to Venice that transformed his work as a superb painting of the interior of Santa Maria della Salute bears witness. Meanwhile back in Scotland, Stanley Cursiter was excited by the radical new art of the Italian Futurists. He brought their work to the Society of Scottish Artists in Edinburgh and himself painted a number of essays in their dynamic, fragmented style. One of the loveliest things here, a luminous gouache from the 1920s by EA Walton of a farm near Florence, is more straightforward, however. The advent of travelling scholarships took the likes of William Wilson to Italy in the 1930s. A superb print of Verona is a witness to his travels. William Gear and James McIntosh Patrick found themselves in Italy in very different circumstances serving in the Italian campaign. Both found time for art in the midst of war. Patrick’s River Scene near Capua is tranquil enough, but in Gear’s fiercely drawn Olive Grove the war does not seem far away.

In the post-war years, travelling scholarships resumed. Alan Davie, taking up an award postponed by the war, underwent an epiphany in Venice when he saw Jackson Pollock’s work. His own best work followed over the next decade or so and here Serpent’s Breath is a fine example of its power. Joan Eardley was in Italy at the same time as Davie, but she engaged with the life and the landscape as she does in a drawing here of a market. Elizabeth Blackadder followed a few years later and Italy inspired a series of magnificent drawings like one here of Siena.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

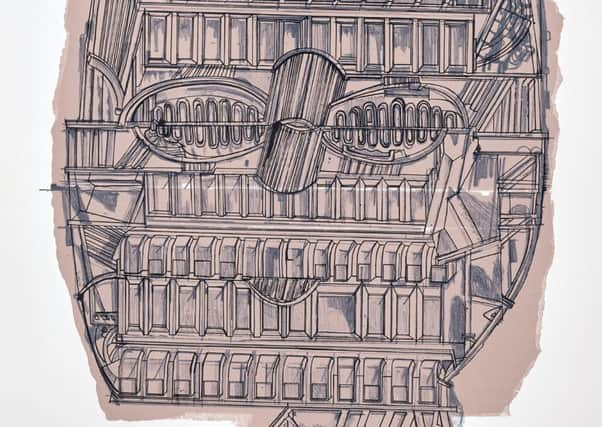

Hide AdNor should we forget that the exchange went the other way, too, and was no less fruitful. Eduardo Paolozzi and Alberto Morrocco were both Scots born of Italian parents and both made distinguished contributions to the land their parents adopted. Paolozzi is represented here by a schematic bronze of a horse’s head, typically made originally in concrete, Morrocco by a characteristic still life, with vivid colour set against a black ground. There is more too. Altogether this is a rewarding show.

Modern: 20th Century Art and Design at the Fine Art Society is more miscellaneous, but a number of things do stand out. It is an unexpected pleasure, for instance, to come across a group of Graham Rich’s small fragments of experience, his unique seascapes conjured miraculously out of fragments of sea-worn wood. Big pictures in a small compass, they find a fitting partner in Talbert McLean’s beautiful Abstraction in Green and Red, small enough in fact, but big in impact.

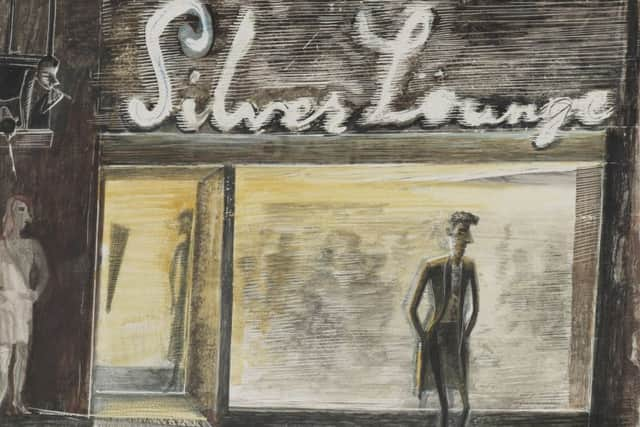

There is a very grand Paolozzi here, a lithograph Homage to Picasso. But there is also a show within a show of work, old and new, by John Byrne. His picture-making skills as we see them in First Date, for instance, are always breathtaking, but in a recent self-portrait they are honed down to an austere subtlety that is quite outstanding.

The Italian Connection until 24 May 2020; Modern: 20th Century Art and Design and John Byrne: Then Till Now both until 9 November