Art reviews: Hugh Buchanan | Will Knight | Beneath the Surface

Hugh Buchanan, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh *****

Will Knight: Some of Summerhall, Summerhall, Edinburgh ***

Beneath the Surface, City Art Centre, Edinburgh ****

The Enlightenment was just that. It brought light where there had been darkness, the darkness of bigotry that had consumed Scotland: the tyranny of belief only validated by the strength of its own conviction. David Hume and his friends were determined that truth validated instead only by experience should forever banish bigotry. The greatest monument of the Enlightenment they led was Edinburgh’s New Town. In volume of stone shifted it is the equivalent of the Pyramids. Appropriately, too, light brought in by wide streets and big windows was at the heart of the project. Light matters too for the classical detail that adorns its buildings. Originally designed for the white limestone and sharp light of the Mediterranean, it was adapted beautifully to the soft light of the north and the gold and grey stone of the city.

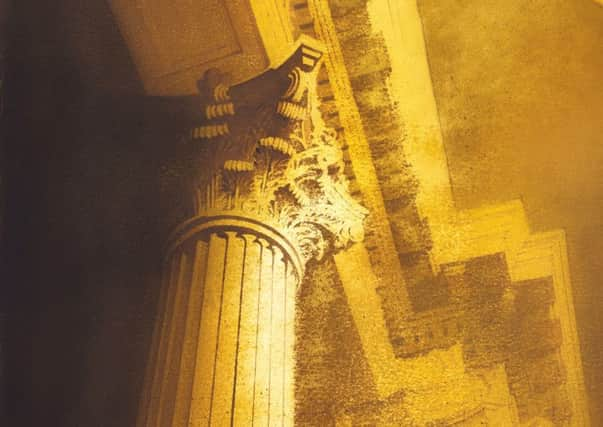

Hugh Buchanan celebrated the quarter millennium of the New Town (while the city largely ignored it) with a superb exhibition of paintings of Edinburgh’s Georgian architecture. Now he has returned with part two, he says, of the same project, not to repeat himself, but to take it in a new direction. Buchanan paints in watercolour, a medium uniquely suited to painting light and his previous show was literally luminous. But, as the wheels of history turn and shadows threaten to overwhelm the Enlightenment’s legacy, so too light does not always illuminate. Bright light dazzles. It can seem to dissolve solid surfaces, make it difficult to see even as it illuminates and, casting deep shadows, it can bring darkness and obscurity into the full light of day. Some of this anxiety is reflected in the direction that Buchanan has taken in his new show. In it he paints details, especially capitals and columns, doric, corinthian or ionian, and fragments of colonnaded facades, but whatever his subject, light dissolves or shadow threatens to engulf it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe describes how first he paints heavy paper with the colour of stone. In different lights this can be black, grey, sepia, or under decorative lighting even pink. Then he attacks it with an abrasive, literally scrubs away at it as though it really was stone. Under this attack the white paper shows through the paint as patterns of light or the texture of the stone. Then he finds the image in this painted and abraded paper. Thus his process mimics the whole business of building with stone, an inert material, cut, polished, shaped, installed and then standing for centuries weathered by time.

In a superb series of grey-black paintings of the entrance to Old College, of other details of Adam’s building, or details of the Doric columns of the RSA, sweeping abrasions seem to reveal the stone’s geology before any human intervention, as the immensity of geological time dwarfs all human effort. Indeed time seems to be the theme of these remarkable pictures. Sepia light suggests old photographs with their unique ability to collapse the distance of time past. Others are on paper roughly shaped and presented as though they were historic fragments, or in yet others the stone itself seems to be eroded as though, in some bleak future, like the Sphinx, it had stood for millennia in a sand-blown desert.

In a pedestrian’s view of the Caledonian Hotel in Lothian Road – Buchanan doesn’t limit himself to Georgian architecture – the dissolving light suggests Monet’s Rouen cathedral paintings. In them, too, the artist reflects on time, on history and the apparent enduring solidity of things, but, at the same time and in contrast, under constantly changing light, their mutability and impermanence. In one picture, Ionian white and gold, a detail of a Corinthian capital from the Signet Library, Buchanan also quotes from TS Eliot’s “The Waste Land”. It is a poem about transience and permanence, about the persistence of memory across great stretches of time, just like classical architecture laden with its history over 2,000 years and more. Eliot also contrasts all this collective memory with the mundane, transient details of life, day to day. In his pictures Buchanan invites us to look about us and like Eliot to reflect on these imponderables.

At Summerhall, Will Knight has also made art out of architecture, but there the resemblance ends. Whereas Buchanan has taken details and made them in into art, Knight has simply enumerated them, all of them, every minute bit of the former Dick Vet School which is now the Summerhall complex. He has measured and itemised everything and then painstakingly drawn plans and elevations in pen, freehand but apparently to scale, filling dozens of sheets of paper with his annotated drawings. Then, building on all this information, he has produced a set of charming small drawings, all simple elevations, in pen and watercolour. It is all very impressive and one day in the future, people may be intrigued to see what it was all like, but it rather suggests art at a loss looking for a purpose and so does seem just a little forlorn.

With no documentary purpose, nor even external reference, the work of the abstract artists in Beneath the Surface at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh nevertheless really has more in common with Buchanan than does Knight. They are artists for whom in many different ways the being of art is also its sufficient end and purpose. The exhibition catalogue has a fascinating and informative essay by Kenneth Dingwall about Scotland’s relationship with the idea of abstraction at once boldly pioneering and pathetically timid, the Caledonian Antisyzygy again perhaps. Dingwall cites Arthur Melville, William Johnstone and Norman McLaren as pioneering spirits, but then reminds us that modern (Modernist) art was not officially recognised institutionally until the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art was created in 1960. It is good to be reminded that these artists have such pedigree and that they represent the eventual triumph over timidity. Nor do they lack anything in confidence or accomplishment. Dingwall himself, for instance, has a striking, narrow, vertical relief, a set of inverted and incomplete steps in scarlet, titled Pending.

Michael Craik’s square paintings in acrylic on aluminium have the richness and translucent depth of classical porcelain. Eric Cruikshank paints in oil on paper, graduating pure colour through degrees of saturation, or shifting from warm tint to cool with magical effect. James Lumsden creates translucent clouds of shifting colour, aptly titling one example Liquid Light. Others are called Fugue and the analogy between abstraction and music has always been important. Karlyn Sutherland creates perspective space with simple geometry and just three tones of blue-grey. Alan Johnstone uses an equally simple but carefully harmonious geometry of rectangles, differentiated by varied surfaces of paint and pencil marks. Sarah Brennan pulls off something similar, if improbable in tapestry. The way wool absorbs light makes her blacks contrasted with white and grey peculiarly rich and intense. The only sculpture here is by Andrea Walsh, a set of simple glass dishes containing eggs, or perhaps they are simply sea-worn pebbles in gold, platinum and white. Callum Innes’s Exposed Painting: Pewter Violet is a wonderful demonstration of something fundamental to this whole topic. The sheer beauty of paint and canvas, or indeed any other medium fastidiously handled, is sufficient poetry in itself. Indeed Innes’s generic title, Exposed Painting, says it all.

Hugh Buchanan until 23 December; Will Knight until 8 March; Beneath the Surface until 1 March