Art review: Making It: Sculpture In Britain 1977-1986 | Stephen Collingbourne | Robert Powell

The new show of sculpture at Edinburgh City Art Centre is called Making it: Sculpture in Britain 1977-1986. Those bracketing dates seem not so long ago to be already history, but long enough ago to be largely forgotten and if so, it is good to be reminded of a decade that is indeed only a rather misty memory. Most of those included were born after the war, a generation therefore for whom the great innovations of the earlier part of the century were no longer simply overwhelming, but now far enough away to be looked at and learned from with some detachment, though the predominant use of assemblage and found materials suggests that Picasso, Dada and Surrealism still remained the primary inspiration.

Making It: Sculpture in Britain 1977-1986 | Rating: **** | City Art Centre, Edinburgh

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStephen Collingbourne: Don’t be afraid of Pink | Rating: **** | City Art Centre, Edinburgh

Robert Powell: Species of Space | Rating: **** | Edinburgh Printmakers

Some of the artists, like Tony Cragg, Anthony Gormley, Anish Kapoor, Richard Deacon and Cornelia Parker, have remained familiar. Others seem to have vanished from the record although their work nevertheless seems interesting. Using two floors of the art centre, the show is displayed in a way that makes you realise that these sometimes rather gloomy galleries can actually be light and airy. This greatly helps the sculpture, because, if it has a common quality, it is lightness and insubstantiality. As though in reaction to the bulky steel, bronze and stone of the previous generation, much of it is loosely assembled and transitory rather than solid, permanent or monumental. Tony Cragg’s New Stones: Newton’s Tones, for instance, consists of small fragments of broken plastic objects, (plastic is now as much part of the beach as stones) apparently scattered on the floor, but overall assuming the colour bands of the rainbow. Shelagh Wakely’s Sine Qua Non is simply the outline of a pair of sandals drawn in brass wire. Kate Blacker’s Mont St Victoire pays homage to Cézanne, but with loose sheets of corrugated iron painted to mimic his brushwork and supported by the branch of an actual tree as his compositions often are by a painted one. It is playful and that is the most attractive quality of much of the work here. Bill Woodrow’s Crow and Carrion, for instance, is made out of two broken black umbrellas, one the crow, the other the carrion it is tearing apart. One of the nicest pieces, Jean-Luc Vilmouth’s Five Heads, is composed of a pedal bin, a dustpan, a shovel, a builder’s trowel and an enamel coffee pot, all with eyes cut in them to make five comical heads. Richard Wilson’s Say Cheese is a camera tripod that has morphed into a bizarre figure, as though subject and object have become one.

Some of the work is more solid however. Anish Kapoor, for instance, is represented by the The Chant of Blue, four large, enigmatic shapes coated in pure pigment, two matt black and two intense blue. Nicholas Pope’s Fifteen Holes consists of 15 large carved wooden doughnuts standing on their edges. Eduardo Paolozzi, who might have been expected to figure more largely, is represented by Head Looking Up, a bronze which, though small, has a monumental feel quite different from anything else here.

But to return to the title, those bracket dates suggest some special historical episode, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Searching the catalogue, it turns out that 1977 was the date of an exhibition; 1986 seems merely to have been the date of an article in Art Monthly, hardly a historic moment by most people’s reckoning. Much of the work on view also comes from the collection of the Arts Council of England and this was the decade in which its influence was at its most potent. Using public money to support the arts was admirable, but one unforeseen consequence was the empowering of a new bureaucracy of curators and art administrators and the separation of visual art from its natural base in wider public opinion. Much of the work here could only ever be displayed in the precious environment of an art gallery. Maybe the show does represent a turning point, but not necessarily for the better.

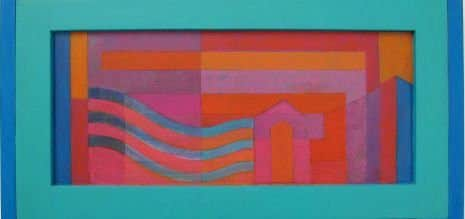

Don’t be afraid of Pink by Stephen Collingbourne is also showing in the City Art Centre. Collingbourne is best known as a sculptor and two of his works in steel are displayed in the foyer, but this is a show of vividly coloured paintings. The words of the title were the advice of a tutor when he was a student. Certainly he has followed it here. Pink shouts out from the walls supported by intense blues, yellows and greens, all in purely abstract arrangements, but with hints of figure and architecture here and there.

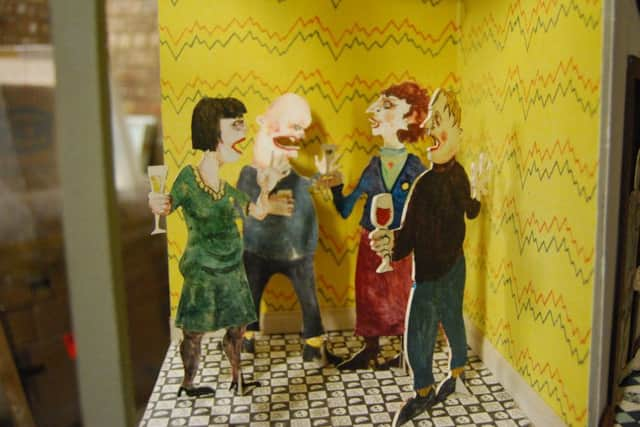

At Edinburgh Printmakers, Species of Space is a very welcome chance to see an extended display of the work of Robert Powell, an artist who has often caught my eye in the big group shows. His intense, complex and often dark prints show him to be an heir to James Ensor, George Grosz, Thomas Rowlandson and the long tradition of the grotesque observed that stretches back to Bosch. His prints are generally not big, but are intricately drawn with countless figures engaged in all sorts of bizarre activities, sometimes in apparently enormous spaces. He enjoys looking into houses and buildings and there are dark undertones everywhere, usually also illuminated by classical and literary references. Saturn and the Sphinx, for instance, represents a father and son looking at Goya’s bloody image of Saturn devouring his Children with an obvious sinister inference. There are also two of the artist’s remarkable large, composite works. High Rise is a tower, each floor with four rooms, and each room containing a dramatic scene which is also given a title. A scene of murder in the bathroom, for instance, is titled Hygienic Assassination: the Ablutional Intervention of Charlotte Corday, an unglamorous, modern reprise of David’s painting of Marat assassinated in his bath. The other construction is called Species of Space or the Amazing Visible City. It is a convex semicircular terrace of street fronts, each window again revealing bizarre goings on within. Beyond the terrace, at the centre of the circle that it would form if complete, springs what looks very like the first stages of a modern Tower of Babel, and that would be a good alternative title for this remarkable body of work.

• Making It and Stephen Collingbourne until 3 July; Robert Powell until 16 July