Aidan Smith: Hipsters will hate supermarket vinyl but this is why we should cheer

It looked along the high street, or what was left of the traditional small shops after its long reign of terror, cheap prices, free parking and complimentary coffee.

It peered through a window at a bearded man behind the counter squinting into the middle of a circular piece of black plastic, as if searching for some cryptic message, and, completing this devotional scene, two customers, also male, solemn but happy, as they thumbed through racks of square-shaped cardboard, presumably containing more of the discs. And this is what the supermarket did just 24 hours later: it formed its own record label dedicated to vinyl.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn truth there is probably no connection between the manufacturers of everything from teabags to toilet cleaners plotting to cut supermarkets out of the equation with Sainsbury’s move into the music biz.

But if this is not the last roar of a dinosaur, then it does seem like a particularly callous act. If you’re worried about everyone hating you for killing off the corner shop and the long-standing neighbourhood butcher, then you don’t go after independent record stores.

Everyone loves them or, at the very least, admires how they’ve seen off the giants in their field to enjoy the revival of needle-to-groove music.

But is it such a cruel thing? Like the day I first set foot inside a record shop with a birthday fiver burning a hole in my pocket, to be confronted by a choice between a copy of Roxy Music’s For Your Pleasure on one hand and King Crimson’s Lizards on the other, I can’t quite decide.

Hipsters will hate that vinyl can now be bought from under the same roof as potatoes and bin-liners. These people have images to maintain (and trousers to roll up). But who cares what they think?

Such is the snobbery surrounding second-generation vinyl that you wonder how many of these records are ever played. If you remember how often discs were bought faulty or how easy they were to damage, you wouldn’t. I’ve re-bought albums on vinyl – having between times purchased eight-track cartridge, cassette, CD and highly expensive, remastered, every-rubbishy-outtake, anniversary versions in the digital format – and have simply been too scared. Still, I bet the sound is lovely and crackly and warm.

We cannot be too sniffy about supermarkets selling vinyl. Woolworth’s were big players in music in the 1960s and 1970s and shifted tons of LPs. They specialised in labels like Pickwick and Hallmark, budget collections of Jim Reeves and the heedrum-hodrum of Caledonia, but also plenty of groovy choons, some of them note-for-note copies recorded by a heroic house-band capable of being easy-listening before lunch and punk after it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI know because one of these compilations, Christmas-themed so naturally the woman on the cover wore a Cossack-style hat with an itsy-bitsy bikini, was my very first album, the one I never admitted to owning while striving for credibility and acceptance among my junior-muso peers.

Sainsbury’s has been selling vinyl for a while but the first records bearing their Own Label imprint are compilations. They’ve been curated by Bob Stanley, Britain’s pre-eminent pop historian.

One of his earlier themed albums, which gathered up all the no-hit wonders inspired by the Beatles to try out a cor anglais or harpsichord, became my most-wanted for a few years until I finally won a copy on eBay for the sum of (amount deleted in case my wife reads this).

Stanley, from the band St Etienne, says he’s trying to put music back on the high street. Growing up, he loved being able to search Woolies and Boots for records as well as the dedicated stores. The albums he found may not have been the coolest on the block but they introduced him to songs which were “life-changing”.

Supermarkets make hypocrites of us. We lament the closure of all the shops which couldn’t compete while cheerfully continuing to be suckled by these retail monsters, whole milk or semi-skimmed.

Ah, but surely shopping for music, and particularly vinyl, should be an altogether different experience – a challenge, a quest or an adventure. If you’re really lucky, all three.

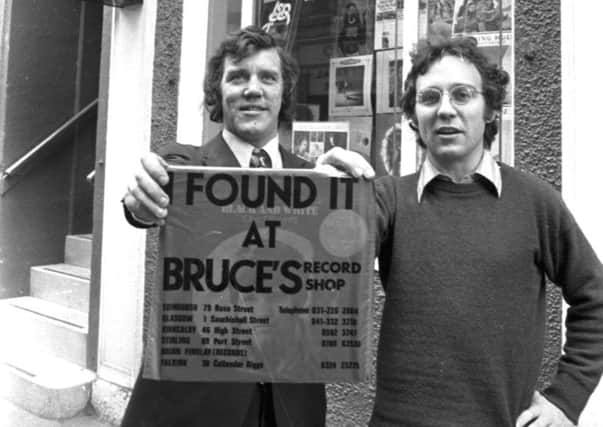

In my early teens, not knowing much, record-buying was inconvenience shopping. The stores were cramped, smelly, noisy, randomly arranged, intimidating and elitist – in essence, everything that supermarkets aren’t.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut you wilfully subjected yourself to this tie-dye tyranny of hippies blowing smoke in your face and sniggering when you asked them for, say, Gilbert O’Sullivan’s ode to a dog (it was for my wee sister, honest).

These ritual humiliations – immportalised in the record-shop movie High Fidelity where the staff take pride in running a “facist regime” – were part of growing up.

If you could summon up the courage to return your purchase when it jumped all the way through side two then you were halfway there.

By the way, that first vinyl dilemma was solved by choosing neither Roxy Music nor King Crimson but Pink Floyd’s Relics – for just 99p. I spent the rest of money on a new pair of jeans and was clearly a supermarket-lover in the making.