The Highland bothy that tells the story of an abandoned place and its people

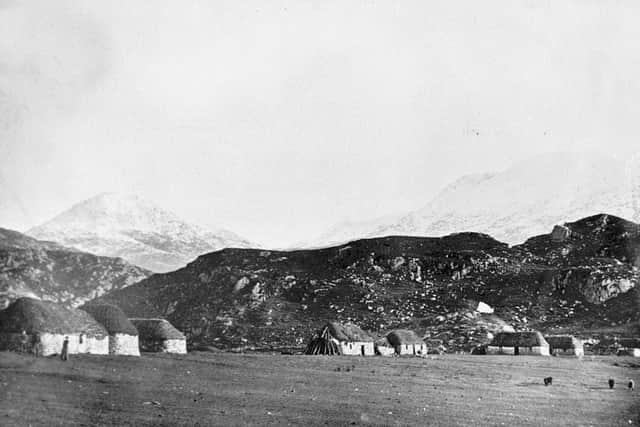

It was the last house to be abandoned at Peanmeanach on Ardnish – a peninsula once home to possibly hundreds of people, with the door closed on the bothy for the last time in 1941.

The last residents Margaret MacDonald, the old school mistress and her brother-in-law Sandy, watched their neighbours go one-by-one as war, hardship and emigration pulled the people out of this place, where fertile growing grounds give way to a sandy beach and views over to the Isle of Eigg.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMargaret, who raised six children alone following the early death of her husband and also ran the school and post office, hung on long after she took the last class.

People had been here for thousands of years, with the remains of an Iron Age fort in view of the bothy and the remains of a Viking boatshed down on the shore.

But come the mid-20th century, it was time for the MacDonalds to leave.

Iain MacQueen, of Arisaig, Margaret’s grandson, said: “They were ready to go. There was no family left, there was nobody to teach. The Post Office was finished because there was nobody there. There was no post.”

Peanmeanach had fallen increasingly silent over time, but once it buzzed with families, children and a life of hard work.

When Ms MacDonald arrived from Barra to teach at the school in 1901, there were 28 pupils in class.

The Clearances had pushed people onto the peninsula from surrounding lands owned by art collector Lady Ashburton.

In 1829, one farmer was listed as living on Ardnish, but by 1841 there were 200 adults now settled here – and possibly the same number of children again. Overcrowding and the push for a share of little work, food and income ultimately forced many to leave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt Peanmeanach, there were 48 people living in seven houses. Within 100 years, no-one remained.

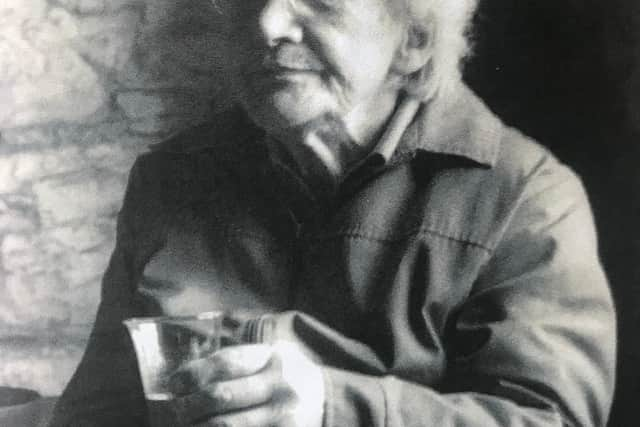

In 1998, Nellie MacQueen, one of Margaret’s daughters and mother of Iain, returned to Peanmeanach for the last time.

Then in her 80s, she picked up a stick, walked the line of cottages and said out loud the names of the people who once lived there.

A roll call of Smiths, MacLellans, MacGillivrays and MacDonalds heard amongst the derelict bothies, now just memorials to those who called them home.

She pointed out the burn where the washing was done and showed where she planted blackberries and rhubarb in a roofless byre.

Nellie remembered the fun of sliding down the big rock by the school into the water, of ghost stories at night, and ceilidhs at Glenuig or Lochailort, which could go on until 5am.

Mr MacQueen, whose mother died ten years ago aged 96, said: “The family were self-sufficient more or less. They dug their own potatoes, fished and killed their own sheep. They used to make their own black pudding. They knew how to look after themselves.

“It was so isolated there, but they were always talking about how happy they were there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was a hard life. They were really tough, but they knew no different. My mother was as strong as a man.”

The 1883 Napier Commission records hardships at Ardnish.

Donald MacVarish, 68, gathered whelks for a living, which he described as the best source of income given all other occupations had failed. He would earn five shillings in a five to six-day spring tide.

Droving cattle and sheep to Falkirk had offered the most money, but the coming of the railway did away with that. Later, the building of the Fort William to Mallaig line also created work, but this too ended.

The future hopes of Peanmeanach were perhaps pinned on one of the MacDonald sons, Christopher, who Margaret adopted as a child from Glasgow.

He went to war in 1939, but never returned. He was killed at Saint-Valery-en-Caux in 1940 at the age of 21 and was deeply mourned.

War also took Nellie away when she joined the Women’s Land Army at the British Aluminium factory in Fort William.

When she returned in 1998 to see the village, she was asked if she regretted leaving. No, was the answer.

After the MacDonalds left, their home was as a byre for 20 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to Peter Stewart-Sandeman, owner of Ardnish Estate, the village was leased in 1967 to Reverend Geoffrey Shaw, who brought children from The Gorbals to his “Highland university by the sea” that he created after being inspired by good works he did in East Harlem, New York.

An old lobster boat called the Og was purchased and roofing materials from a blown-down house in the Gorbals was used to re-roof the bothy.

The plan was to buy the village, but one night a sheep was killed with a bow and arrow and the deal was off.

In the 1970s, the MacDonald’s old home was given to the Mountain Bothy Association, with the door left open for adventurers to use.

It was recently taken back by the estate, who have refurbished the property and will rent it out privately, given reports of large groups who headed there to party for the weekend.

The guides that would lead these visitors to Peanmeanach describe Ardish as a remote, wild place, empty of people. But it was not always this way.

A message from the Editor:Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by Coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.