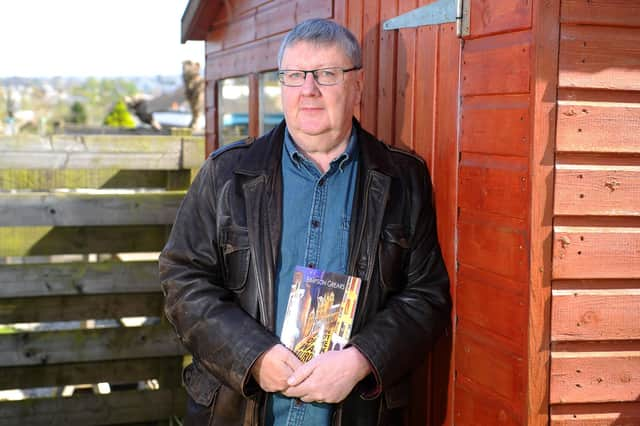

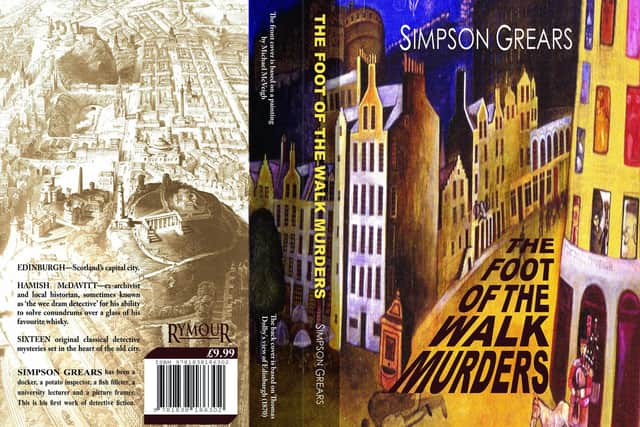

The Foot of the Walk Murders, by Simpson Grears, Pt 2: Violent deaths rock Leith and Edinburgh

Ord flicked through the album. All the scenes, set against the reconstructed buildings, featured burghers, or servants or fishwives posed around the set.

‘Of course,’ eventually added Ord, ‘there is a link to the case. I believe it has been suggested that all of the victims were employed at the exhibition as models, and that Johnny Monkey may have worked on the construction of it. He may have met them there.’

Advertisement

Hide Ad‘So, in fact,’ added Hamish, ‘the faces of some of the fishwives we see posing here could be those of the victims themselves!’

Ord hesitated. ‘It’s a queer thing, looking at old photos like these and for all we know we may be gazing into the eyes of someone who is shortly to be murdered. It’s quite thought-provoking.’

‘It’s a queer thing altogether looking at any photo, perhaps,’ said Hamish. ‘All the people pictured in these photographs are long dead. But no-one remains as they are pictured. We all age and eventually die. Because a photograph is a frozen moment in time. A moment that can never be recovered – perhaps that is why photographs fascinate us.’

Ord looked a little disconcerted for a moment. Perhaps the thought of all and sundry as inevitable victims of the final Reaper was too much for him to contemplate, but then he rallied.

‘We’ll keep these for further discussion,’ he said, ‘but let’s plod on with the Ripper case.’

The book gave a fair outline of the case itself. The fact of the matter was that in late August of 1886, three murders had been committed around the area of Leith at the bottom of Leith Walk. On the fifteenth of August, Annie Sloan, a poor but respectable scullery maid, had been discovered brutally murdered in a dark alley behind the Kirkgate.

Advertisement

Hide AdOn the twenty-sixth of August, the body of Elsie Pierce, described as a ‘drudge’, but almost certainly a prostitute plying her trade around the area of the docks, had been found in a derelict back yard in Giles Street.

The final victim, Mary McCutcheon, found on the thirty-first of August, had been similarly despatched, but there were some small differences in her case. She had come from a slightly better family than the others and had a decent job as a housekeeper in the Mount Royal Hotel in Princes Street. She had been found in a washhouse behind a townhouse in Pilrig Street, nearer Edinburgh and the New Town. She had also been pregnant at the time of her death.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe cases had caused a great panic on the streets of Edinburgh and Leith, but the press reports had rather glossed over the full horror of the crimes: ‘All the ladies that have met their unfortunate end have been shamefully violated in a way that no lady of either high or humble birth should be. They had faced their Maker in the commission of the unspeakable act and had been finally dispatched with the aid of a common gutting knife ubiquitously carried in the Port of Leith by fishermen, dockers and sailors.’

In fact, as Peer-David’s book made clear, with the aid of some shockingly graphic photographs rescued from the police archive, the poor victims had been brutally sodomised whilst held around the throat. Before the end of the ordeal, the murderer had used his other hand, and his knife, to violently rip open their stomach, practically disembowelling them.

The pathologist’s reports were detailed in the book and were of particular interest. In fact the first two examinations had been conducted by probably the most famous medical practitioner in Edinburgh at that time, Joseph Bell a lecturer at Edinburgh University. Bell was an innovative surgeon who developed a system of deduction in examining medical cases. He was said to have been the inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes.

The third examination, due to Bell’s absence on university business, had been undertaken by his almost equally well known colleague, Dr Vincent Imrie, a giant of a man who delighted in the grisliness of his occupation and had been known both for the vigour with which he pursued his profession and his non-conformity to the social mores of the time.

To, illustrate this, Peers-David had included a caricature portrait of him from the London Illustrated News showing him brandishing an extremely vicious-looking dissecting knife above a partially dissected corpse as his students fainted in circle around him.

They spent a moment or two glancing at the illustrations, ‘Classic sex crimes,’ commented Ord. ‘Obviously the perpetrator could only achieve a climax through an extremely violent act. We know a great deal more about such murders these days, but in those days such things weren’t really spoken of; it seemed all too impossibly horrific for the Victorian middle-classes to stomach. And there were few advanced tests available, no DNA tests or anything of that nature. There was no psychological profiling, nothing like that.’

Advertisement

Hide AdIn fact, none of these techniques had proved necessary. The common and accepted solution to the case was succinctly outlined in the book. The case had been solved, apparently, by one of the most renowned Scottish detectives of the day, Chief Inspector John Lambie, on the very same day as the last murder.

‘Lambie, a great figure’, said Ord, ‘A real policeman’s policeman.’

Tomorrow: The Mystery of Johnny Monkey