Wales legend JPR Williams recalls Wimbledon and that '˜99 call'

In April ’68 tennis’s open era began. Previously amateurs and professionals competed separately with the latter barred from Grand Slam events. The first open tournament was the Hard Court Championships of Great Britain in Bournemouth and indeed a Scot is credited with hoisting the first serve – John Clifton, in his match with Australia’s Owen Davidson. Ah, but just before that contest, the qualifiers had played and they included 19-year-old John Williams from Bridgend, Wales, who’d already secured financial benefit for his endeavours – the princely sum of £20.

Despite that distinction, however, Williams would turn his back on tennis. He tells me: “My father was firmly opposed to professional sport – he was a corinthian – and said that if I played anything for money he would never speak to me again. It was hard to give up tennis but he was firm about it: ‘You will go to university, study medicine and combine that with your rugby.’” Williams exited Bournemouth when he was beaten by another Aussie, Bob Howe. “We were on court two hours and then I drove back to Bridgend, just in time for the 7.15pm kick-off against Newport. Twice I caught Stuart Watkins from behind – he was the Wales winger at the time – and I think that clinched my selection for the tour of Argentina.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe second revolution happened in rugby. After September ’68 you could no longer boom the ball into touch from anywhere on the field – direct punts would only be allowed behind the old 25-yard line. So who would be the prototype for the counter-attacking game? Step forward, our young student at St Mary’s Hospital, London.

“I was very lucky in my career,” says Williams, who wore his country’s fiery red with 15 on the back all through the glorious 1970s. “Rugby changed and that suited my style.” So what happened to the twenty quid? “Well, first I established that it was okay for me to keep it because rugby was very, very amateur back then. Then I had to buy the rest of the Bridgend lads a drink and that was my tennis winnings gone.”

Williams, now 66, has just returned home to the village of Llansannor (pop: 200), tucked away in the Glamorgan countryside, after one of his regular games of squash. While he scuttled down the far end of the house to take my call on the extension, with a detour to the kitchen for a beer, I asked his wife Scilla how I should address him. “Hopefully you’ll get on well enough that you’ll call him John,” she said. “He was always known as John until J.J. Williams came along, then it became JPR.” Yes, the most famous three initials in sport after lbw, and so embedded have they become that when you spool back the tapes on his pomp it’s a surprise to hear commentator Cliff Morgan shriek: “John Williams! John Williams!” Scilla was telling me that older friends call him Japes when he picked up the other phone.

The voice was once described as being “as rich and Welsh as a deep seam of coal”. It’s mellifluous, for sure, and when I ask what he’s like as a singer Williams confirms he’s a member of two choirs, but he’d be the first to admit there isn’t much trace of coal dust in it. A middle-class lad and the son of two GPs, he says: “I was never more embarrassed than when I turned up at a Wales Schoolboys’ trial in my father’s Rolls-Royce. All the other lads stared at me, open-mouthed.” Far from give him a sense of entitlement, his comfortable background made him strive harder, tackle tougher. “I thought I had to prove myself. And when I got into the big team I knew I had to impress the miners.”

The “luck” to which John Peter Rhys Williams refers only took him so far. You don’t greatly assist your team to eight Five Nations, six Triple Crowns and three Grand Slams on good fortune alone. And what a team: Gareth Edwards, Barry John, Phil Bennett, Gerald Williams, the aforementioned J.J. Bread of Heaven in the stands, rugby from heaven on the pitch, sidesteps and sideburns as prerequisites.

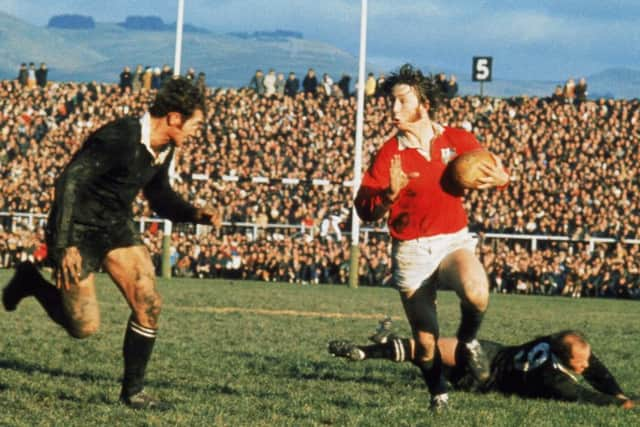

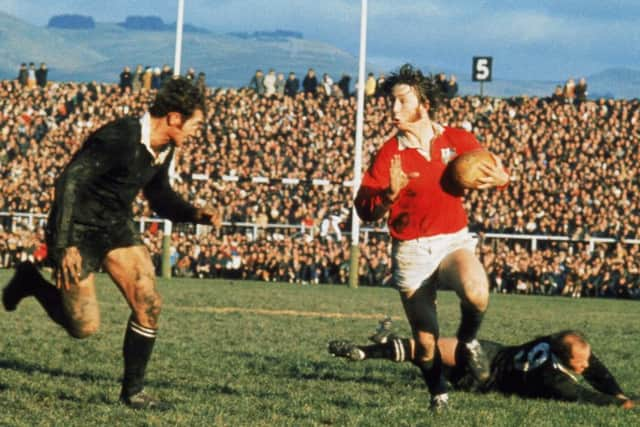

Let’s talk image because in 1970s sport, even with so much hair around, Williams really stood out. The flowing locks were sometimes tethered with a Geronimo headband. The socks were always round his ankles. The muttonchops were as verdant as those sported by Noddy Holder, that bloke from Mungo Jerry and the master and commander of TV’s The Onedin Line. He would have been a marketing man’s dream if such types were around back then, but thank God they weren’t.

“When you’re young you want to be different,” he says. “I wore my socks down because I used to suffer cramp. I always liked long hair and still have it now.” So what does he make of this piece of purple prose from Carwyn Jones: “The figure of Williams in the distance, hair flying in the wind, may remind us of Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed, riding majestic and mysterious in the mists of Mabinogi …” – a bit over the top, perhaps? “No, I think it’s rather splendid!”

Jones was playing his Olivetti like a symphony orchestra piano following a typically baroque performance by Williams against England: he scored two tries and required seven stitches to a face wound. JPR recorded a 100 per cent win rate against the English. A fierce rivalry always, but the 1970s – assorted strikes and the holiday-home controversy – lent it a political edge. “Phil Bennett when he was captain used to deliver some stirring speeches. ‘They’ve taken our coal, our steel, our water,’ he’d go. ‘They’ve taken our homes to live in just two weeks of the year. They’ve even taken our women!’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJPR and his brilliant boyos, though, didn’t have things entirely their own way against us. He talks warmly of Wales-Scotland games as the countries prepare to do battle in Cardiff today, also of the Scots who became Lions team-mates and friends. “Because no caps were awarded in Argentina, my first was at Murrayfield in 1969, still just 19. Mervyn Davies was playing his first game too, and I remember us walking along Princes Street, not quite believing how many Welshmen had come up for the game. The night before it the team went to the cinema, which was a tradition. My parents closed the surgery and drove straight to Edinburgh. I waited up for them until past 11pm which became a tradition too. Some of the boys had a couple of drinks to help them sleep but I never did on the eve of a match, saving myself for afterwards.

“I was nervous before kick-off but early on I caught a ball close to the touchline and heard a voice: ‘John, pass me the ball.’ This was Barry John who promptly kicked it to within five yards of the Scottish line. I thought to myself: ‘This international rugby is easy!’” Legend has it he never missed an egg falling out of the sky. “Not true,” he adds, “but I was very comfortable under the high, hanging ball.” The hand-eye coordination he brought from tennis helped, Williams beating David Lloyd to win Junior Wimbledon and also securing a world under-age title in Canada with victories over future Top 10-ers Sandy Mayer and Dick Stockton, although he reckons that if he’d disobeyed his father Peter’s instructions and kept hold of his racquet he’d have achieved Davis Cup at best. The old man took all four Williams brothers to the fearsome Methyr Mawr sand-dunes and shelled them with up ‘n’ unders. “The other three didn’t turn into rugby players but they did become doctors and worked in the same practice as my wife until we all retired and unfortunately there are no Dr Williamses in the Bridgend/Ashfield district anymore.”

Wales won Williams’ debut and the next three against Scotland. He says these were close matches and it’s true they included the 19-18 epic back at Murrayfield in ’71 – “Secured at the death with John Taylor’s kick, the greatest conversion since St Paul” – but what about the following year’s 35-12 trouncing at the old Arms Park? “Ah well I don’t remember much about that one because I clattered into Billy Steele. I was carted off to hospital while the game raged – depressed fracture of the zygoma. The surgeon fitted my brace and told me: ‘You better go back and have a couple of large gin and tonics to lessen the pain.’ Sound advice.”

As a doctor on the spot in 1970s rugby Williams would often be required to make an assessment on an injured player. “I had to do this for our opponents as well, which was tough, because if the guy on the deck was one of their top men we maybe wouldn’t have minded him being removed. But before you ask, I never misdiagnosed deliberately to gain us advantage!”

Clobberings involving JPR, either sustained or dished out, have passed into rugby folklore. On the 1974 Lions tour of South Africa, in a provincial match against Natal, he caught local hero Tommy Bedford with a right hook, sparking a near-riot. Cans of beer – full ones – rained down on the pitch from the top deck and one fan went after Williams with a stick. JPR is not proud of that, although points out he apologised to Bedford afterwards, whereas he received no apology from New Zealand’s John Ashworth who stamped on him in 1978. “I could feel the studs near my right eye, then my cheek bone clunked,” Williams wrote in his autobiography, “leaving a horrendous hole all the way through to my tongue.” He was stitched up by his father on the touchline before returning to the fray for Bridgend. Peter mentioned the incident in an impromptu speech, prompting an All Blacks walkout. “I wished Dad hadn’t said anything but he was an emotional man.”

The South Africa tourists ended up being crowned the Invincibles but there has been some recent coyness over the part played in that mission by the “99 call” – one of our guys gets thumped, everyone takes out the man nearest to him. Williams, though, insists it was used, with the full-back sprinting 40 yards to biff Johannes van Heerden. “I’m not proud of that either and remember that Phil Bennett and Andy Irvine were running the other way. But years later I bumped into Johannes on a train and he told me my punch was the best he ever received.”

Williams eulogises the roles played by Scots on that Lions expedition and the one to New Zealand in 1971 when a rare JPR drop-goal clinched the series. “Guys like Mighty [Ian McLauchlan], Sandy [Carmichael] and Broon [Gordon Brown] were terrific tourists. Broon was one who performed better on tour because he had to train every day! We all miss him hugely and I hold dear the memory of a great get-together at Grosvenor House shortly before he died – it was his last supper. Obviously the story of [Springbok] Johan De Bruyn getting two entire packs to scrabble around in the mud for his glass eye was told again. And De Bruyn was there to hear it – the mark, I think, of a great man.”

JPR’s opposite number in the early days of Wales vs Scotland was Ian Smith: “A lovely guy but not that quick.” Andy Irvine was a more formidable opponent – “A great runner and a prodigious goal-kicker” – although perhaps lacking Williams’ Zen-like calm under a ball hurtling earthwards, snow on top. On the ’74 Lions tour JPR was asked to tutor him in the art. He also taught Billy Steele how to drink, with rather less success. “Billy was my room-mate, a very fine fellow. After winning the second Test we went up to Kruger National Park and had a bit of a spree. It lasted five days and Billy found it tough going. I’m afraid he faded from the tour after that. But he taught all the non-Scots the words to Flower of Scotland and I’d like to think we all remember them still. He’s not really had acclaim for that and he should. Arriving for the next Test the bus stopped but we were still singing. No one got off until the song was finished.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScotland on home turf would beat Williams’ Wales in 1973 and again two years later in front of a gigantic 104,000 crowd, on St David’s Day as well. The Dragon roared in the next four encounters before JPR missed 1980 in the wake of a “shamateurism” row over his memoirs. “I made no money from that book – it went into a sports injury clinic which is still open. But when I wrote another book in 2006 I made sure I kept the proceeds!” He returned for the ’81 fixture at Murrayfield which would end his career where it had begun, with a defeat. “All of the backs were dropped but it was the forwards who were at fault.”

After that Williams would rise to eminence as an orthopaedic surgeon. His fame forced him to carry out separate “rounds” – one for patients seeking only his tender mercies, the other for autograph-hunters. He probably thought it wrong for sportsmen to be idolised when, a few years ago, he was hit by a drink-driving ban.

He liked having a proper, demanding job to which to return after the Saturday skirmishes and reckons the modern player must be thoroughly bored, training all the time and watching video re-runs. There’s a lot about the pro-game which frustrates him, not least its attitude to head injuries. He’s currently writing a medical paper on the issue and you imagine that like everything he’s ever done it will be hard-hitting.

JPR played on at a lower level until he was 54, always to win. “The competitor of competitors,” he was once dubbed. Presumably he’s not scared of anything. “No no,” he splutters, “I’m absolutely terrified of my wife.”