Scots pair proud to have played a part at seismic 1995 World Cup

Truth be told, the 1995 Rugby World Cup final wasn’t a great bout, certainly no Rocky Balboa v Ivan Drago, and the Eastwood-directed film Invictus of 2009 can’t compete with Richard Burton’s 13-man rugby league code classic This Sporting Life of 1963. But what that day at Ellis Park represented, on 24 June just over 24 years ago, went way beyond sporting aesthetics.

A year after his election as president of South Africa, a prospect deemed unimaginable a few years before, the sight of Nelson Mandela in a Springbok jersey and baseball cap, handing the Webb Ellis Trophy to South Africa’s white Afrikaaner captain Francois Pienaar was said to be the moment the “rainbow nation” was truly born.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRugby was seen as the white man’s game in South Africa back then, with soccer the passion of the black majority who would get a football World Cup to enjoy with vuvuzela-soundtracked exuberance a decade and a half later.

In these fraught political times we know all too well that life is not like a movie, with neat happy endings, and South Africa did not become a Utopia the moment Joel Stransky struck the winning drop goal in extra-time to conquer the seemingly unbeatable All Blacks. But, as they enter this year’s World Cup with a black captain in flanker Siya Kolisi, it is surely worth acknowledging the iconic nature of that 1995 tournament, which was one of those moments that survives the clichéd line about “transcending sport”.

Less than three years after their readmission to international sport following decades of being boycotted during the despicable decades of apartheid, the rugby-mad nation seized on its opportunity and lapped up those few weeks in the spotlight, culminating in that unforgettable image of Mandela handing the silverware to Pienaar.

Sport is a fun escape in life, often vacuous and trivial as even those of us who spend our lives playing and reporting on it must admit, but occasionally it acts as a cultural pillar. Jesse Owens in 1936, the Lisbon Lions in 1967, whisper it softly but even the red-shirted Three Lions of ’66 or Jonny Wilkinson in 2003, the Rumble in the Jungle in 1974 or Andy Murray’s first Wimbledon win in 2013.

These kinds of seismic moments leave their mark on us. But that 1995 World Cup went beyond simple human achievement, supreme athleticism and the gift of chucking, booting and whacking a ball about.

Beyond the political realm, it was the first time a World Cup had been hosted by one nation, following the joint antipodean inaugural event in 1987 and the Five Nations tourney of 1991. New Zealand and England have hosted the last two and now the first “emerging” rugby nation Japan gets its chance to shine. They have a movie of their own in the can, with The Brighton Miracle set to give celluloid honour to the Brave Blossoms’ groundbreaking victory over the Springboks on the Sussex coast four years ago.

Who knows if that will be one of those rare sporting films that make it past the two-star mark but it is still and only about a game, the 1995 World Cup in South Africa was about the building of a new nation.

The Scots who played a part in the tournament, which came on the cusp of the sport’s switch from the amateur to the professional eras the following season, are well aware and proud of their part in the story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

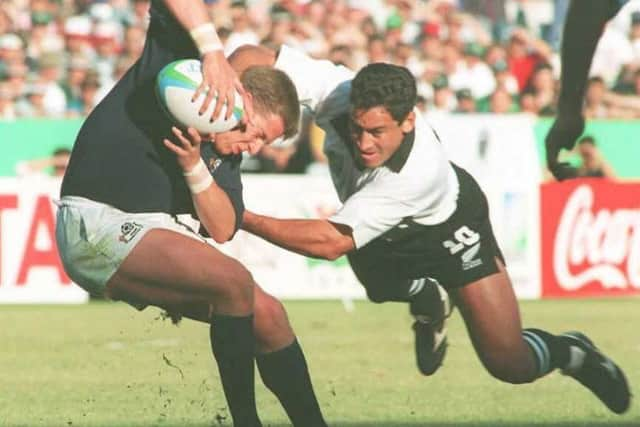

Hide Ad“You could sense how much they were thirsting for it having spent so much time in the political wilderness,” recalled ex-tighthead prop Peter Wright, who played in all of Scotland’s games in that campaign, which started with a briefly held World Cup record 89-0 win over the Ivory Coast and ended with a 48-30 defeat by the Jonah Lomu-driven All Black express train in the quarter-finals.

“We were mainly based in Pretoria apart from that first game against the Ivory Coast in Rustenburg,” continued Wright, inset below left.

“We were at nearly four and a half thousand feet which took some getting used to. We’d done a bit of altitude training in Spain which was a shock to the system so we were prepared but these were still the amateur days. We didn’t have the kind of training and preparation the boys over in Japan now have, but we were international rugby players so we did get to grips with it.”

Full professionalism was coming soon and that 1995 World Cup was held under the backdrop of its looming shadow. The late Australian billionaire Kerry Packer was floating his attempt at a “World Rugby Championship” similar to the World Series Cricket he had launched in the 1970s.

Scotland stand-off and one of the 1990 Grand Slam heroes, Craig Chalmers, also played in every game of that 1995 campaign and remembers the time well.

“I still have a signed contract for the Kerry Packer thing somewhere. A lot of the boys in the squad had signed up for it but, in the end, it got the unions around the world into action and the sport went open soon after,” recalls Chalmers.

Current Scotland coach Gregor Townsend was in the thick of that situation, as can be read in his excellent autobiography Talk of The Toony, but he wasn’t at that World Cup due to injury, which meant Chalmers added further caps to a tally which would eventually reach 61 in 1999. Both he and Wright take pride in the fact they played a part in a tournament which would go down in human history let alone rugby. Chalmers has watched Invictus but Wright has not. As straight-talking as ever, the Bonnyrigg Blacksmith perhaps speaks for a generation who grew up in the era of the Spitting Image show’s memorable ditty, I’ve Never Met a Nice South African.

“I just don’t like South Africans, they’re an arrogant lot,” said the former Lions prop. “Individually there’s a lot of South African players I’ve admired and liked and I look back on 1995 with fond memories. Friendly welcoming people but there is an arrogance there.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“After they won it, their president Louis Luyt made a speech at the official dinner saying that South Africa were the first true world champions because they hadn’t been involved in 1987 and 1991, and the New Zealand captain Sean Fitzpatrick got his team to walk out on the spot, and then the English and French teams did too.”

Scotland, who enjoyed a trip to the Mala Mala game reserve during the tournament, which both Wright and Chalmers describe as one of the greatest experiences of their lives, came unstuck on the park when losing 22-19 to a late Emile Ntamack try in the pool decider against France. It meant they would have to face the onslaught of the All Blacks back at Loftus Versfeld in the quarter-finals.

“We could have been heading to Durban to play Ireland,” explained Chalmers. “That was the days when we always beat them. I think I was nine and zip against them in my career. I’ve had painful defeats but the dressing room after that France game was one of the worst. We knew guys like Big Gav [Hastings] were going to be finishing after the tournament and knew we’d lost an opportunity.”

Wright is also still niggled by that loss but recognises it pales into insignificance compared to a more tragic event earlier in the day. “We could have won that game,” he recalls. “I remember there was some niggle in the build-up. We’d beaten the French in Paris for the first time since 1969 in the Five Nations that year, with the famous Toony flip pass which put Gav in under the posts. So they feared us.

“Some story came out in the South African press that the Scotland squad had wrecked a local restaurant, which was total nonsense and we all reckoned it had been the French camp that had put it out to get under our skin. But what I remember most is that the Ivory Coast v Tonga game was on before ours and we were watching it and saw the terrible injury to the Ivory Coast wing Max Brito. After our game had finished we heard he was on life support and I just wasn’t bothered that we had lost to France any more. It certainly put things sharply into perspective.”

The sad story of Brito, who was paralysed from the neck down after being crushed at the bottom of a ruck, is one of the many human tales that came out of South Africa 1995.

Only last weekend the iconic black Springbok winger Chester Williams’ untimely passing added to the sadness of others who would participate in that famous 1995 final. Springbok coach Kitch Christie, who attended Leith Academy in his teenage years, died three years later in 1998 after a long battle with cancer. Since then, the world of rugby has lost South Africa scrum-half Joos van der Westhuizen to motor neurone disease, back-row Ruben Kruger to a brain tumour and James Small, the wing who faced up to Lomu in that final, of a heart attack aged 50.

The great Lomu, left, was lost in 2015 to kidney failure. Our own beloved Doddie Weir remarkably outscored the Kiwi titan two tries to one in that 48-30 quarter-final loss and now faces his own battle, with inspiring spirit, against MND. Japan 2019 will write a new and fascinating chapter but, in terms of wider significance beyond the joyous field of play, South Africa 1995 will long stand as a totem in the history of rugby union football.