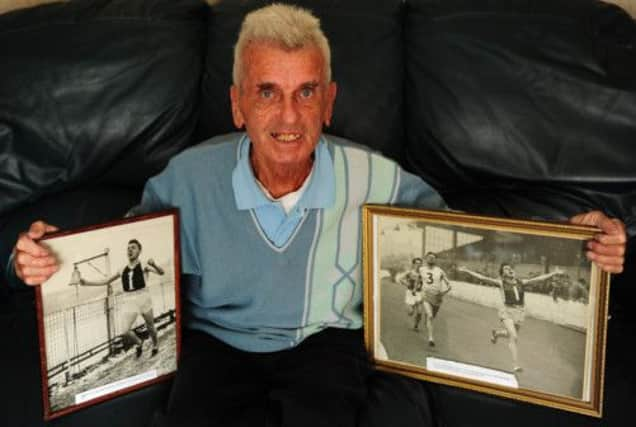

Michael Glen, the monarch of the mile

In a running career that spanned 26 years, Glen competed in thousands of races on track and over hill and was the “king” of professional middle distance running. So much did he dominate that, at his peak, he often had to start 30 yards behind the scratch mark to offer some hope to his rivals.

Now a sprightly 80-year-old old, despite the legacy of arthritis and knee and hip replacements from his running days, his enthusiasm still burns brightly as he recalls his career.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis “day of days” was at the Keswick Games in the Lake District when he set a new world and British professional mile record on grass. “That Bank Holiday meeting was a big event, part of the annual Keswick Show in Fitz Park in the town. Professional running was very popular in the Lake District and had a long tradition. There must have been over 20.000 people there that day – a great atmosphere!

“The grass track was just laid out for that event and had a slight rise towards the finishing line. I hadn’t set out specifically to beat the record but I’d been in good form. I was the backmarker off scratch conceding handicaps up to 250 yards to my 25 or so fellow competitors. I threaded my way through the field and crossed the line in 4min 7sec to set a new world and British record, beating the legendary Walter George’s mark of 4m 12sec set back in 1886.”

The obstacles posed by so many rivals and the deficiencies of a rudimentary grass track surely detracted from his performance?

“I reckon if it had been a proper track with a limited field of quality runners, including a pacemaker, I could have got the time down to about 4m 2 or 3sec.”

Nowadays, when four-minute miles come along as often as buses, that might not seem particularly noteworthy. But, set in the context of its time, it was a tremendous achievement. Roger Bannister’s iconic four-minute mile had been run only 15 months previously with the help of certain advantages denied to Michael. His was achieved on a carefully prepared cinder track, aided by two [strictly illegal then] accomplished pacemakers – Chris Brasher, later Olympic gold medallist at steeplechase, and Chris Chataway, later world record holder at 5,000 metres – as part of a race, with no more than six runners which was deliberately set up as an attempt on the four-minute mile.

Nor had Michael spent the morning of his race machine-grinding his spikes to a fine point to extract every advantage as Bannister did.

Setting the scale of Michael’s feat further in context, the amateur Scottish mile championship that year was won in 4min 13.2sec, while the British AAA championship was won in 4m 5.4sec.

“I would have loved to have run against Bannister and in the Olympics but it was not to be. Discreet enquiries were made on my behalf after my Keswick record about me joining the amateurs, but the response was a curt “No”. You see, by then, I had been running as a professional for about 11 years.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat “professional” career began for Michael back in 1944, when aged 11, he won the “boy’s marathon” at the Paulville Gala Day Sports in Bathgate, earning him a small cash prize.

A local trainer, Jimmy Gibson, a friend of his dad, took him and some others under his wing and soon had them running at games across the country. As prizes were in cash, Michael and his young pals were all deemed professionals. In those days, there was a wide chasm separating the amateurs from the professionals, with the latter being unable to compete in big international events like the Olympics.

“I never really had any personal issues with the amateurs of the time. We trained in our groups and they trained in theirs. I knew some quite well, including Graeme Everett, the top Scottish amateur miler of the time. He was a fine lad. Another top amateur I got to know was the famous Gordon Pirie, who was also a smashing guy. He turned professional not long after the Rome Olympics and I actually ran against him – and beat him – at Jedburgh Games in 1962. We got talking about the amateur/ pro issue and, when I told him my level of winnings, he thought the “amateurs” did much better overall – first-class travel all over the world, all expenses paid and “bonuses” thrown in.”

But for Glen, it was not about the money. Yes, it was welcome, but he explained: “I loved running for itself and it became a way of life for me, virtually. I went all up and down the country competing – in the summer at Highland games in the north, Central belt and Fife, at Border Games in the south and at hill races, particularly in the Lake District.

“In the winter, my main focus was on the Powderhall New Year events for which I would go on “special preparations” for six weeks at a time. In summer, on a good week, I could win up to about £60 or £70. Sometimes you’d also be paid petrol expenses and appearance money. It doesn’t sound much now, but then it was about two or three times a working man’s weekly wage. But competing and winning were the really important things for me. I just had to be the best, that was what drove me.

“I think I got that from my dad. He’d been a miner and instilled that will to win in me. My three brothers Neil, James and Edward, and my sister Mary were all good runners who had success at the games, but it was my will to win that made me better.”

Arguably Bathgate’s most famous sporting son, Ryder Cup captain Bernard Gallacher, also benefited from Michael’s single-mindedness and his physical conditioning expertise. When Bernard’s golf career began to take off, it was to Michael that he turned for assistance with fitness training for his sport.

“Bernard was a very nice guy, very down to earth. He used to come up to our garage to do weight training with us and then join us running. His family lived nearby at the time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough shunned by the amateurs as an active athlete he, was, by contrast, welcomed into the amateur fold as a coach in the late 1960s when his own running career was winding down. He became a highly-rated middle distance coach, accredited by the sports’ governing bodies. During most of his career, he was self-coached but an avid student of coaching methods.

In 1969, he received a Churchill Fellowship Athletics Scholarship to travel to the USA to study coaching methods there.

“That was a fantastic experience for three months in Los Angeles San Francisco and New York. I learned from top American coaches, including Olympic ones. Actually, at the end of my trip I was offered a coaching job in Los Angeles but family circumstances prevented me taking it.”

The next year, he was invited down to the Guildhall in London where he was presented with the Churchill Fellowship Gold Medal by the Queen Mother. That completed a nice double for Michael as, in 1955, he had been presented to the Queen at Braemar Highland Games.

These days, Michael has no hands-on involvement in the sport, but still follows it closely. Though his own trackside days may be over, a wealth of trophies and memorabilia on discreet display in his house testify to a career spent at the top.

Twice a winner at Powderhall, winner of countless championships and races at Highland and Border Games, 14-times winner of the world’s oldest continuous foot race, the Red Hose at Carnwath, established by Royal Charter in 1508 and, of course, that Keswick race with his British record there still standing 58 years on.

During his career, the emphasis was on competing and winning, often as many as four track races and a hill race the same day. As a result, times suffered. There was no opportunity to “peak” to achieve a special time in one particular race, nor were there pacemakers to facilitate that nor tracks as good as the amateurs’.

Perhaps with these advantages, the four-minute mile would have been possible for Glen.