Harold Davis, the Iron Man of Ibrox, will forever be a Ranger

But then life isn’t fair. Harry was robbed of two years of his professional football career after suffering devastating injuries while serving with the Black Watch in Korea. Against all the odds, he returned to play for Rangers before heading for a quieter life in the Wester Ross village of Gairloch, where he might reasonably have expected to avoid physical harm. Twenty years after arriving, initially to open a hotel, he sustained a broken neck in a serious road accident near Oban.

The Iron Man of Ibrox seemed indestructible. Which brings us to Gerrard, the new Rangers manager, and his legitimate command to his new charges, which went public this week. “We go to win the ball all over the pitch – get it in your head now!” he yelled in a short film that attracted a lot of social media comment. This is the point. Many Rangers fans seemed to be going overboard about such a simple instruction, one, surely, that should be taken as read for professional footballers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was taken as evidence by supporters of a revived code of conduct at Ibrox, a return to an old Rangers way: shirkers should not apply. It brought to mind Harry, who has passed away at the age of 85. He was a true bearer of the Rangers torch. He couldn’t abide those who failed to make the best of themselves or had no desire to do so. Harry refused to compromise even if it meant getting the wrong side of another Rangers icon in teammate Jim Baxter. The smell of booze on the talented Baxter’s breath in the dressing room before games was an affront to Harry’s keenly felt ethics.

“Once a Ranger, always a Ranger,” he later wrote in his autobiography, Tougher than Bullets. “That was the motto we lived by. For Jim, though, that didn’t seem to apply. It didn’t feel like he cared about the club, only himself.”

Once the recently negotiated deal with Hummel expires the Rangers training centre will need a new name. It’s not exaggerating Harry’s deserved status at the club to suggest a new one: the Harold Davis training centre.

There is no finer example for young players of what it should mean to play for Rangers. He was an embodiment of selfless sacrifice. There has been no finer ambassador for the club during these recent, difficult years, when Harry continued his unstinting support for the Rangers Supporters Erskine Appeal. As patron and guiding light, he was instrumental in its ongoing success to raise funds for the veterans’ charity.

This association was formed due to Harry’s experiences with the Black Watch. These details elevate Harry’s story above, I think, pretty much everyone else in the Scottish football firmament. There’s no question his tale is unique. Not only did he return to professional football from after the near fatal injuries sustained in active service in Korea, he then went from strength to strength, playing in a European final with Rangers – 1961’s Cup Winners’ Cup defeat by Fiorentina – and winning four league championship medals, two League Cup winners’ medals and a Scottish Cup one during eight years at the club.

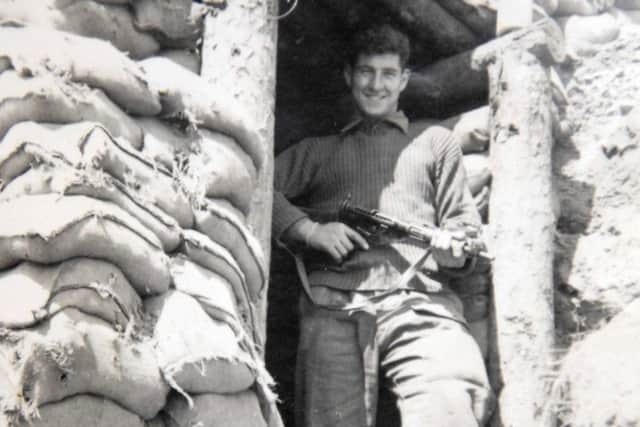

East Fife had retained his player registration while he was in Korea, as well as the long rehabilitation process. But they didn’t expect to see him back. No one did. After all, according to a telegram to his parents’ house in Perth, Corporal Harold Davis had been placed on the “dangerously ill” list after being gunned down at the Hook – a ridge around which intense fighting took place – in May 1953. His surgeon, upon learning his occupation, advised him to consider something else. As well as multiple stomach wounds, he had a shattered heel bone.

Harry battled back, recuperating latterly at Bridge of Earn hospital. The physio there was Dave Kinnear, the former Rangers player. He pushed Harry hard. Scot Symon, his manager at East Fife and who had since moved on to Rangers, heard through Kinnear that his old player was not only still alive, he was getting fitter every day. Symon sent word for him to come to Ibrox.

None of this I knew when the sports editor suggested going to see Harry for a piece ahead of Remembrance Sunday in 2006. I was dimly aware of his name but perhaps more in the context of Dundee. Harry was the assistant to Davie White when Dundee won the League Cup in 1973, the Dens Park club’s last major honour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI sat rapt for hours as I listened to his incredible story. Now and then he would get up to retrieve items to illustrate his tale. One such treasure was a model of a Sputnik 1 satellite gifted to the Rangers squad on a pre-season trip behind the Iron Curtain in 1962. It still ‘bleeped’ like the real thing when switched on.

Dusk fell across Gairloch Bay in the distance. I clicked off the tape and made moves to leave. After all, a five-hour drive back to Edinburgh loomed.

Harry and wife Vi wouldn’t hear of it. They insisted that I stay the night, making up a bed and setting another place at the dinner table. I will always be able to check the date of this memorable trip because it was the same day as Paul Le Guen’s Rangers side lost at home to then First Division side St Johnstone in the CIS Cup: 8 November, 2006. Another cup tie, Hibs v Hearts, was being shown live on BBC Scotland, so the score updates from Ibrox would flash up on the screen. First: Rangers 0 St Johnstone 1. Then, finally, to Harry’s evident disgust: Rangers 0 St Johnstone 2.

As I wrote in the piece, published a few days later, it was difficult to avoid blushing on behalf of the Rangers players as news of a new low in the Le Guen era reached Wester Ross, and the home of someone who could never stand for such a lowering of standards. To make it worse, another Ibrox man of substance and one of Harry’s team-mates, Bobby Shearer, had passed away the previous day.

The next morning, Harry took me to the shores of Loch Maree, near where he rented a bothy. He told me he had made a vow to himself to move to the area on a trip as long ago as 1959. He co-authored a book called, simply, Fishing in the Gairloch Area. Fly fishing, for trout especially, was his enduring passion. The author information contains neither mention of Rangers nor events in Korea, further proof of his humility.

I visited once more, in 2007. The last time we saw each other was five years ago, when the Dundee League Cup-winning side reunited for a 40th anniversary dinner. On that final trip to his and Vi’s home, he went to his garage to fetch a framed Dundee team group from the era. He gifted it to me along with a couple of fish trays he said were ideal for growing seeds in.

I’ve just checked and they remain in the garden, barely visible beneath great bushes that have shot up in the decade since.