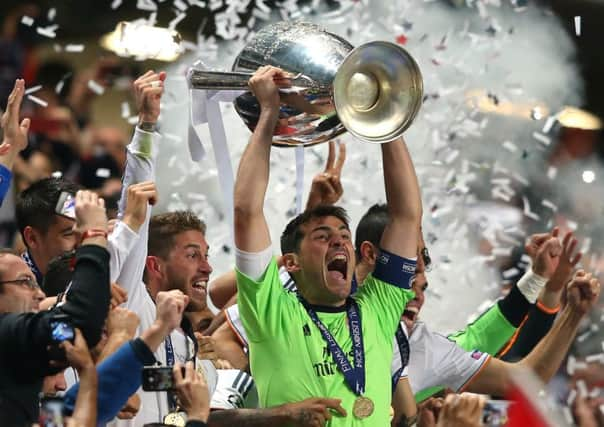

Real Champions League feat would prove cash is king

SOMEBODY, sometime, is going to win back-to-back Champions Leagues and, frankly, when it happens, you’d like it to be a team worthy of the honour. It’s been a quarter of a century since Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan defended the European Cup and the failure of any side to do it since is the story of modern football.

Money, and thus talent, has gathered at the top clubs and so, where it was once possible for a team, through an exceptional generation of players, an inspired manager or tactical innovation, to break from the pack and dominate for two or three seasons, now there is a clutch of sides who, for reasons of wealth, sit above the rest and share out the prizes between them. Once the European Cup felt like the Holy Grail, to be attained only after an epic quest: now there’s a sense that, if you’re rich enough for long enough, it will eventually come your way.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe quest is now to win it twice, a prize that twice slipped from Pep Guardiola’s grasp at Barcelona in implausible circumstances – in 2010 the Icelandic volcano meant they had to travel to the away leg of their semi-final against Internazionale by bus, followed by the extraordinary resilience of Jose Mourinho’s side in the second leg; and then Chelsea’s combination of courage, discipline and fortune frustrated them in the second leg of the semi-final in 2012.

That Barcelona team, by general consent, was one of the greatest sides the world has known. In the 25 years since Milan’s second triumph, there have been other great sides who have come close: Louis van Gaal’s Ajax, Marcelo Lippi’s Juventus, Vicente del Bosque’s Real Madrid, Carlo Ancelotti’s AC Milan. Alex Ferguson must look back at Manchester United’s quarter-final defeat to Real Madrid in 2000 and wonder what might have been. As the journalist Miguel Delaney, who is writing a history of the European Cup, observed last week, it would feel strangely “out of sync” if, after so many great sides failed, it was this Real who succeeded.

And yet at the same time, what could be more in keeping with the preoccupations of modern football? No club is more representative of the money-driven, celebrity-obsessed culture than Real Madrid, with their president Florentino Perez who sees breaking the world transfer record as part of a marketing strategy and then insists his icons play even when they are out of form and even when they seem to distort the shape of the team.

In a Champions League quarter-final of many sub-plots, which stands at 0-0 after the first leg, the financial disparity between Real Madrid and Atletico is one of the more intriguing. According to Forbes, Real Madrid are the richest club in the world, worth £2,300 million and with an annual income of £450m. Atletico are worth £220m and have an annual income of £105m. They are still the 17th-richest club in the world and are sponsored by Azerbaijan, while a number of their players have been secured through third-party ownership deals that would not be possible in the UK. But, while it would be wrong to portray them as some fairytale outsiders, neither are they part of the elite. Rather they, like Borussia Dortmund, are a member of the group of major clubs who are not super-clubs who can, every now and again, break through and briefly challenge Europe’s grandees. Their life at the top, though, is limited. They have to endure the sale of a key player or two each summer and, as Dortmund’s struggles this year have shown, no side can keep on regenerating for ever.

By winning La Liga last season, coach Diego Simeone achieved something remarkable by winning a two-horse race when he wasn’t even riding one of the two horses but, in time, the miracles will yield to economic reality and he will find himself, like Dortmund’s Jürgen Klopp, looking for a new challenge, preferably with somebody richer, with a club that doesn’t find its centre-forward disappearing to Bayern or Chelsea.

Atletico haven’t been able to maintain the astonishing form of last season. Before yesterday they lay third in the table, nine points behind the leaders, Barcelona. Their squad hasn’t coped with the rigours of the weekly grind of the league. They have, perhaps, missed the goalscoring of Diego Costa and the goalkeeping of Thibaut Courtois, which turned defeats into draws and draws into wins. But they have been able to raise themselves for the biggest games. When they play Real on Wednesday, it will be their eighth meeting of the season. Atletico are yet to lose.

This is part of the paradox of Atletico – they are better against better sides. Their strength is sitting deep, remaining compact, absorbing pressure and striking on the break. With Arda Turan and Koke playing extremely narrow on either side of what was ostensibly a 4-4-2, Real found space limited on Tuesday.

Mario Mandzukic, the Croatian centre-forward off-loaded by Bayern last summer, has scored 12 league goals this season – Diego Costa, the man he replaced, got 27 last year – but he offers a bigger, more physical presence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCosta would scrap for loose balls, but Mandzukic has the heft to function as a more orthodox target man, offering Atletico an outlet. His awkwardness and importance to Atletico was reflected in the buffeting he took from Real in the first leg, including an elbow (intent uncertain) from Sergio Ramos that left him bleeding from his eyebrow.

To an extent, Real played into Atletico’s hands. Their 4-3-3, with Cristiano Ronaldo on the left and Gareth Bale on the right, means they lack natural width. Ronaldo naturally cuts infield because he’s always looking for goals, Bale cuts infield because he’s naturally left-footed. The result can be that the three forwards end up playing on top of each other which, inevitably, makes it easier for a team playing narrow to shut down space – as Atletico did superbly in the second half.

Real’s chance, perhaps, was in that first half on Tuesday when they created chances but couldn’t take them. The lack of an away goal could cost them.

Last season, Real had Angel Di Maria operating on the left side of a midfield three, selflessly filling the space vacated by Ronaldo. James Rodriguez, sumptuous player though he is, simply doesn’t fulfil the same tactical role. Ronaldo, meanwhile, has adapted his game as age and injuries sap at his explosiveness. He comes deep far less often and dribbles far less often, exacerbating the issue.

As so often before under Perez, Real have made signings that have destroyed the team’s tactical coherence. They have a collection of great players rather than a great team. Yet the quality of those players, the depth of their resources, means they prosper – perhaps not as much as they should, but enough. Theirs is the football of the rich, taking what is best from others and only then thinking how they may fit in. And, because they are rich, they can keep on buying and mistakes have few consequences.

And that, really, is the difference between the sides. Real Madrid have reached at least the semi-final in each of the past three years and haven’t missed out on the knockout stage under the present tournament structure. They will have plenty of other chances.

Atletico know that, if they don’t win the Champions League this season, there may never be another chance. For them, it is a quest and not simply a game of pass the parcel.