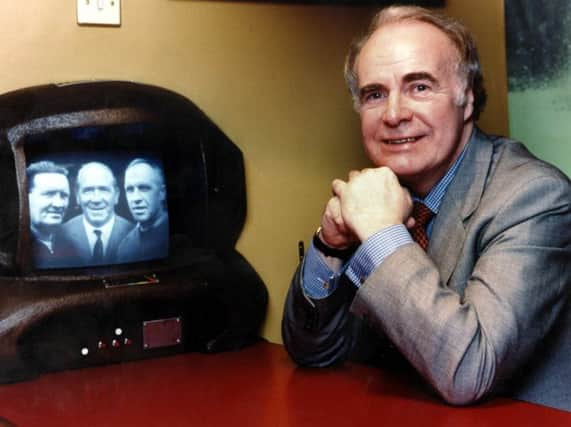

Martyn McLaughlin: End of an era as Hugh McIlvanney retires

A battered and well thumbed anthology of Hugh McIlvanney’s writing on football has pride of place on the bookshelves beside my desk at home. A cheddar proportioned paperback block, it is an ungainly tome but the magic inside seldom fails to inspire.

I had cause to revisit it in recent weeks while writing the script for a BBC radio documentary about Bill Shankly. As a fellow Ayrshireman, McIlvanney had an innate understanding of what motivated the Liverpool manager. Shankly, he once said, was a “warrior poet,” whose sayings became “central to the folklore of the game in Britain”. No-one put it better before or since.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe news that McIlvanney is to slip gracefully into retirement feels like the end of an era, one which began over 60 years ago when he worked at the Kilmarnock Standard, the Daily Express and The Scotsman.

A breakthrough moment in his fledgling career came in the spring of 1960 when he was covering the European Cup final at Hampden for this newspaper. The match, a resounding victory by Real Madrid over Eintracht Frankfurt, is regarded as one of the most exhilarating ties in the competition.

McIlvanney filed his copy to the paper’s Edinburgh office via short bursts of Telex throughout the course of the game. The circumstances of its genesis means that his dispatch now feels truncated in places, but there are moments when he skirts skilfully around the events of the evening to capture perfectly its mood.

“The strange emotionalism that overcame the huge crowd as the triumphant Madrid team circled the field at the end, carrying the trophy they have monopolised since its inception, showed that they had not simply been entertained,” the 26 year-old wrote. “They had been moved by the experience of seeing a sport played to its ultimate standards.”

He has long demonstrated a gift of informing how history will remember a game from the confines of a match report, a medium not known for its permanence. Like his younger brother, the late novelist, William, the elder McIlvanney sibling is capable of a turn of phrase that sweeps you off your feet and leaves you enraptured and, in my trade, more than a little envious.

Consider the scene he painted of Ayr Racecourse on a bracing January afternoon, visited by “the kind of wind that seemed to peel the flesh off your bones and come back for the marrow.” Or then there is his assessment of Scotland manager Ally MacLeod, written in those heady weeks before the national side departed for their inglorious assault on the 1978 World Cup. “During the past six months, MacLeod’s pronouncements on his assignment have shown all the objective restraint of the Highland Light Infantry going over the top,” McIlvanney noted.

Even with the sound of a deadline rushing toward him, he produced prose that sang, words tuned and composed into a rhythm that lent their meaning a rare expressiveness. It was, of course, all a masterful deception.

John Rafferty, Ian Archer, Glenn Gibbons and other members of the erudite, argumentative band of sportswriters who scribbled alongside him often testified as to how McIlvanney agonised over his copy with a gumshoe reporter’s ruthless insistence upon accuracy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Alex Ferguson, one of many sporting giants to pay tribute, recalled how he would call him up at home late night with an urgent enquiry. “McClair, is it a small or capital c?” came the question. Even the irascible Ferguson understood; language was McIlvanney’s craft. Even an errant comma might invite accusations of shoddy workmanship.

His greatest talent was to understand how sport could serve as conduit to articulate life’s universal themes. It was a perception shared by Sir Alastair Dunnett, the former editor of The Scotsman, who helped usher the young McIlvanney towards his calling.

Having covered the trial of Peter Manuel, McIlvanney, then a general reporter, thought he would be a newsman for life. Dunnett, giving him a copy of AJ Liebling’s seminal book, The Sweet Science, saw differently, and set him on a different path.

“On the one hand, Liebling’s standards were liable to frighten the life out of me,” McIlvanney later reflected. “On the other, the book confirmed that writing about sport could be worthwhile.”

The lesson would be imparted beautifully to generations of readers. Perhaps my favourite slither of McIlvanney’s writing is his account of England’s clash with Brazil in the 1970 World Cup, where he gets to essence of his - and their - profession.

“At its highest levels the game can acquire something akin to the concentrated drama of the prize ring,” he explained. “Players go into some matches with the certain knowledge that the result will stay with them, however submerged, for the rest of their lives. Defeat will deposit a small, ineradicable sediment, just as victory will leave a few tiny bubbles of pleasure that can never quite disappear.”

McIlvanney belongs in the same rarified company as Ring Lardner, George Plimpton and Red Smith. His retirement will leave a void in the game and the paper trade. His career has dovetailed with football’s metamorphosis from working class pursuit to global entertainment brand, a journey he, above all others, helped delineate and scrutinise.