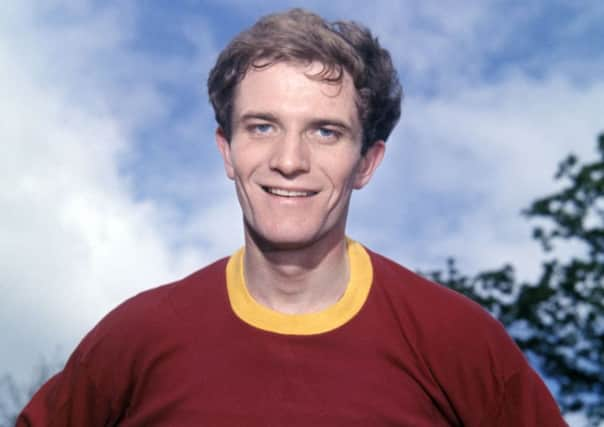

Interview: Willie Hunter on the link between football and dementia

And “wee heiders”. All the boys in the blocks liked to keep footballs airborne, bouncing them off walls or in circled groups, but Roberts and Hunter took the craft seriously, as the latter explains: “On Saturdays after BBs we’d go to the speedway and I’d stay over at Bobby’s house. First thing Sunday morning Bobby’s dad, who played for Tranent Juniors, would cover his old leather ball in boot polish and thread a new white lace and up at Holyrood Park he’d fire over crosses so we could try to score against each other with diving headers, just like Lawrie Reilly.”

In the Queen’s back garden, the king of Scotland’s Wembley comebacks inspired the “Beggie Boys” and, in a few short years, these best friends would become members of the Ancell Babes, the buccaneering Motherwell team who, as the 1950s turned into the 60s, seriously threatened to win the old First Division or the Scottish Cup.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHunter played in what used to be called the inside-left position. A terrific dribbler, he created goals for others but stresses: “I liked heidering the ball, so did every player at that time. I was a wee bloke, five foot seven and a half inches, although that didn’t stop me.

“As I like to remind Ian St John I was a half-inch taller and he was the man in that team and aye heidering the ball.”

Heading might have seemed a nonchalant act for these top practitioners of the game, but when the rains came and the sphere got soaked it turned into a missile. “Oh that was sair!,” adds Hunter with a wince. “One time I got knocked out. I was strapped up like a mummy and so was finished but I remember the same thing happening to St John in a match against Clyde and, with no substitutes in those days, he was sent back on to the park only he didn’t know where he was and started running the wrong way.”

Hunter, 77, has lived to tell such tales; others haven’t been so lucky. So he helps where he can, visiting old soldiers of football, and in the course of their afternoons together he might mention a cup-tie or a crazy goal or a muckle centre-forward, which will unlock a memory long thought lost. “Tomorrow I’m off to see one of my regulars,” he says, “a great favourite in the Hearts team of a while back. We might go A to Z trying to list great players through the alphabet. Or daft players! He’s getting good at this game; last time he beat me.”

Sadly for some, A has come to mean Alzheimer’s and D stands for dementia. “Every week I’m hearing of another ex-player who’s suffering,” adds Hunter. It’s a highly emotive subject and, until now, a contentious one. Can heading a ball really cause brain damage? This may turn out to be a landmark year for those like Hunter who say it does.

At the start of 2017 there was great sadness throughout the Scottish game when it was revealed Billy McNeill was suffering from dementia. How many times had Celtic’s indomitable captain scored with towering headers or stopped attacks with his head, the clearances flying as far as lusty kicks?

But campaigners were cheered in September when First Minister Nicola Sturgeon made a pledge to implement Frank’s Law, extending free personal care to under-65s in Scotland with degenerative conditions. The legislation is named after the late Dundee United full-back Frank Kopel, whose wife Amanda had been pushing for reform since 2013, the year before Kopel was diagnosed with dementia.

Last month, just as America banned heading for children aged ten and under, Alan Shearer investigated the health risk in a BBC documentary. The former England striker conceded that during his career – 46 out of 260 headed goals in the Premier League and for every one, many more during training – he may have damaged his brain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was quickly followed by the promise of new research. Doctors at Glasgow University, beginning next month, are to investigate whether ex-footballers are more likely to suffer from dementia in later life by comparing them with the general population. The announcement came after mounting criticism of the football authorities’ failure to address the issue sooner.

Hunter travelled far in his football life – to Detroit and Cape Town – but has settled in a trim home the other side of Arthur Seat from where he grew up.

In his front room, surrounded by photographs from his career, he nods as I reel off these notable events. Good work has been done, he says, but more needs to happen.

It was five years ago that he began working with Alzheimer Scotland on Football Memories, a project set up by Falkirk historian Michael White. Hunter is the ambassador but cringes at the title. “I just talk to these guys. I know which buttons to press. I can get stories out of them,” he says.

“I’m no doctor but how can heading a heavy ball many times over many years not cause brain damage? I’m worried that football won’t accept this until it’s too late for many of the guys, just like happened to coal miners when they fought for compensation over illnesses specific to their industry.

“I knew a lot of the victims of dementia when they were strapping athletes and, meeting them again at this sad time in their lives, I’ve seen their rapid decline. It’s horrible, heartbreaking. Football needs to do do something quickly because the wives and families are having a terrible time dealing with the problem.”

Hunter has always been interested in his own story; not through self-indulgence but as a survival technique. “I’ve written books and poems to self- medicate my depression. Football didn’t cause it for me; that was family life. My mother committed suicide and my sister died as an infant. My father, sadly, was one of the men of his generation who spent too long in the pub and didn’t look after my mum.” Hunter’s first book was a personal history of Begg’s Buildings, named after Rev Dr James Begg, a campaigner on behalf of the poor. The second charted his time at Motherwell when he sported the claret band 228 times, scoring 43 goals. Two other books followed.

Growing up above Easter Road, Hibernian were Hunter’s boyhood favourites. Though he’d play for them eventually, Hibs tried to sign him when he was promised to Fir Park. “Their scout came round to the house to talk to my dad. We only had two chairs so I was sat on the windowsill watching all the toerags jump on his car. Eventually the scout gave up trying to poach me and ran outside to chase them away.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe dynamic young Well team assembled by Bobby Ancell produced eight internationalists and three top five finishes in the league but couldn’t achieve higher than third. “One problem was the manager didn’t sack the goalie, Hastie Weir, who was murder. I remember him dropping one in the net at Dunfermline and our captain Bert McCann sprinting 40 yards for a big argument. They were slapping each other. We needed to keep St John but he left and wee Quinny [Pat Quinn] soon followed him.”

Full of yarns and still able to fill them with colour and detail, Hunter smiles as he recalls Quinn scoring in the 89th minute against Hearts at Tynecastle in 1958 with our man sealing a notable win in the dying seconds. “At night myself and Jimmy Robertson, who became my best man, went dancing at the Palais, as did lots of players from different clubs. The Hearts boys always wore their club blazers and eyed up the birds from the balcony. I was a good jiver so I was already on the floor and I gave the Jam Tarts a wee wave.”

The fraternity of football was also evident on the matchday train leaving Edinburgh in time for games in the west. “John Greig might have been on it, along with other Rangers guys like Jimmy Millar and Ralph Brand, and Jocky Robertson from Third Lanark. Then on the return journey we’d gather at the bar to talk about our matches.”

In 1960, Hunter’s Motherwell thumped Leeds United 7-0 and Brazilian champions Flamengo 9-2. But the highlight of that year was his Scotland debut away to Hungary. End-of-season friendly it might have been, but 80,000 packed into Budapest’s Nepstadion. “I was in tears during the anthems because I was so proud to be there. I’d only just turned 20 and was on a cloud. I scored our first goal and we had chances to win but the game finished 3-3. Afterwards the team piled into a nightclub. Dave Mackay, John White, John Cumming and myself got up and sang.”

Hunter, who would win two more caps, had his progress hampered by three shoulder breaks. And, even though he had issues with his father, he was reluctant to leave Motherwell if it would mean deserting the old man. A promised benefit denied him by the new Fir Park boss forced his hand, and Hunter and his wife Rona headed for the United States. On the field, Detroit Cougars were “too cosmopolitan” to properly gel as a team. Off it he loved the lifestyle and glamour. Playing in New York ahead of a charity match between Santos and Benfica, he collected the autographs of Eusebio and another guy who could play a bit. “I thought Pele would have a different dressing-room but there he was in the one I’d just vacated, using my peg.” On the same handy envelope went the signatures of tennis ace Rod Laver and actress Jill St John (no relation to Ian).

Hunter’s joy at making it to Hibs was tempered as he was used sparingly by three different managers in his one and a half seasons at Easter Road. There was a single European appearance when he had to fly alone to Vitoria Guimaraes in Portugal, having allowed his passport to expire, while his only goal came in a 4-3 defeat at Morton, the team bus having broken down en route. But, before rounding off his career with South Africa’s Hellenic, once more in the company of St John (Ian not Jill), he made good friends in Leith. “Right through my career, even if the football wasn’t going well, the company was always great. I had a lot of fun with a lot of guys and I still keep up with them.”

Football, in his work as its memory man, continues to bring new friendships, albeit in the most poignant of circumstances. “I enjoy meeting these guys and try to help them as best I can,” says Hunter, closing his scrapbooks. “It’s tragic that something as innocent as heading a ball might have brought them problems. It’s also tragic because in many cases they weren’t paid much for being so bloody brave.”