Interview: Asa Hartford on beating England at Wembley

“Warm-ups back then were nothing like they are now,” says the 50-times capped pocket-battleship of the dark-blue midfield. “These days players get the whole pitch, the drills are structured with specialised coaches and practice goals and everything. We just did our own thing, jumped about a bit, except that day the Massed Pipes and Drums marched diagonally up and down. There must have been 200 of them and all they left us was this wee corner with hardly any room to stretch our legs. Fair enough, though: the park still belonged to them at that point.

“We were glad to have their backing, although we couldn’t quite win the game. Alan Ball’s shot dribbled over the line and I don’t suppose it’s hit the back of the net yet. I was 21 and pretty wide-eyed, especially when Norman Hunter chopped Billy Bremner in half with a tackle. They were club-mates! Then there was Peter Storey: he’d have kicked his own granny. They said Scots were always up for that fixture. So were the English.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHartford is proper Lion Rampant royalty, Scotland elite. Picked by The Doc, Wee Willie and Ally with his army, he then survived Argentina to be selected by Big Jock as well. He got close-up views of Archie Gemmill’s wonder-goal, Joe Jordan’s hand-ball, David Narey’s toepoke and Diego Maradona’s first international goal. He played twice in the Maracana, six times against the Auld Enemy and achieved a Wembley double. Not bad for a guy with a hole in his heart who, at one point, wondered where his next game was coming from, more of which later.

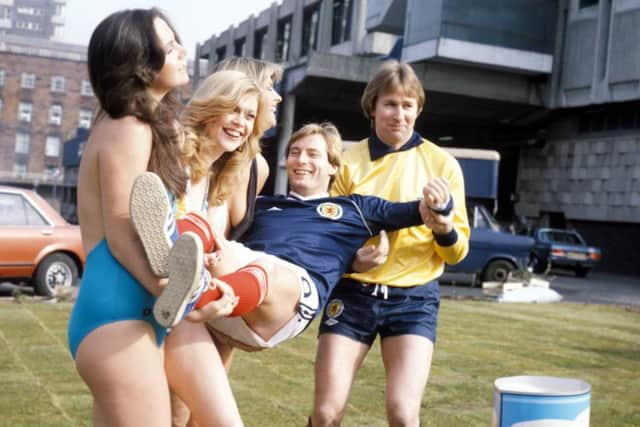

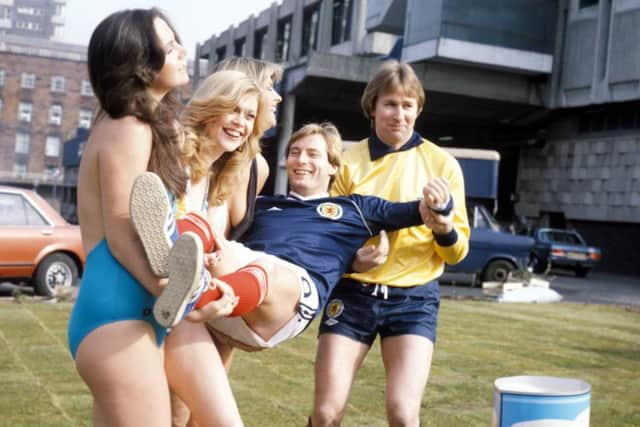

First, though, with Gordon Strachan’s men doubtless leaving nothing to chance in the build-up to Friday’s crucial World Cup qualifier in London, the 66-year-old Hartford offers up another example of the incredible informality of football for his generation, a swaggeringly talented bunch to make you greet for what we once had. It comes from 1981, the second of his Twin Towers triumphs when he was the sole survivor, in either team, from nine years before at Hampden.

“That was the game won with Robbo’s [John Robertson’s] penalty but I was off the field by then, having dislocated my elbow. I’d got a ticket for the game for a good pal of mine, Jim Mowatt, a big trade unionist – he’s now director of education at Unite. As I was being carted off he met me at the tunnel and came into our dressing room. He was sat there for Jock Stein’s half-time team-talk!

“I was lying down, white as a sheet, as the team doctor was trying to pop my elbow back in. Then he decided I should go to hospital but neither of the physios wanted to leave the game – it was Scotland vs England, after all – so Jim jumped in the back of the ambulance with me. The docs put my arm in a sling and we had to go back to Wembley to collect my gear. The final whistle had gone and the crowds were streaming out. Our taxi driver didn’t fancy trying to battle through them so he dropped us some way short of the stadium. When the Tartan Army spotted me, they rushed over and hugged me: ‘Brilliant, wee man!’ I was pretty sore after that.”

Ponder this before we go any further: while today’s players pretend to be on the phone when the great unwashed get threateningly close, or seem to think that designer headphones can function as force-shields, this man didn’t have any option but to move among his people, although he did it willingly. These fans had saved up all year for Wembley; it was the least he could do. They included Hartford’s father Edward back in Clydebank who every two years turned the excursion into an odyssey. “He and his pals used to travel down via Blackpool, spend a couple of nights there, then head straight for Soho. ‘We flicked peanuts at the strippers,’ he once told me.”

Something told me Hartford would be good company in Preston. Maybe it was his apologies for missing my calls, his research to find a good venue for our chat, his apologies for having followed Hearts in his youth. “My dad had a pal in the Army who took me through to Tynecastle to see Hearts play Benfica in the European Cup. I also saw them win the League Cup in 1959 – a birthday treat.” Hartford, by the way, was born on 24 October, 1950, the day after Al Jolson died. His father was a big fan of the great entertainer, christened Asa Yoelson, and that’s how our man came by his name.

Hartford doesn’t disappoint either and gives lie to the myth that football men are not much interested in the world going on around them. We’ve established that one of his friends is a top union official; another is a former BBC journalist. He reads Private Eye and is politically aware. “I think my dad might have been a commie,” he says. “Jock Smith, the school jannie in Clydebank, definitely was.” And Hartford also takes time today to consider the possibly future relationship between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, should the latter be elected US president.

He grew up with his four sisters on the Faifley estate in an upper maisonette and when the local bus turned into the bottom of his street the young lad knew he had time to climb out the window and shin down the drainpipe to catch it. Maybe this taught him how to make the best incursions into the penalty box, such as for his goal against Czechoslovakia on the road to Argentina. The Hearts detail is of interest because, in common with all his midfield contemporaries – Don Masson, Bruce Rioch, Archie Gemmill and Graeme Souness – Hartford was spirited away from Scotland as a youth to become a star in England. He made his international debut in a 1972 friendly against Peru but by then we knew all about him. The whole world did.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFive months previously, Leeds United manager Don Revie had signed Hartford from his first club, West Bromwich Albion, only for the deal to be sensationally called off three days later. Leeds were of course huge back then, a power in the land. The fee was huge – £177,000, a club record. And the cause of the cancellation was hardly a trifling matter. Hartford became known as the “hole-in-the-heart footballer” and it seemed in those strange November days that he was the first person to suffer the condition, certainly the first high-profile sportsman.

“I signed for Leeds on the Wednesday and Don told me I’d go straight into the team to play Leicester City on the Saturday,” he recalls. Revie was desperate to reclaim the old First Division title after two runners-up finishes and Hartford was going to be key to the effort. Even so, he wasn’t sure where he’d get a game in the all-star XI of Billy Bremner, Johnny Giles, Peter Lorimer, Eddie Gray and the rest – in goal, perhaps? “I trained with the guys on the Friday – they handed me the yellow jersey for being the crappest player. I even got my hair cut to club specifications – it was too long for Don’s liking. And then he said: ‘Just one more thing – the medical.’

“I remember having my barium meal and two medics looking at the X-ray and one saying to the other: ‘There it is – look.’ But it was the day of the game in my hotel, the Queens, just as the Leicester players were arriving for their pre-match meal and amazingly Tom Jones was there as well, that Don told me about the hole in my heart so the transfer couldn’t happen. He was in tears. He asked if I wanted someone from Leeds to drive me back to West Brom but I had my own car. I turned on the radio and the story was all over the news. I thought I’d better phone my girlfriend, Joy, and my mum and dad and stopped at a payphone but couldn’t get through to them. By the time I made contact with Clydebank my folks had been told I had cancer. By the time I got to West Brom a reporter had got into Joy’s parents’ house.

“The next week was crazy. Joy and I were moved into a hotel to try and shake off the press. The Midlands’ top heart specialist was saying the hole would have no effect on my playing career, effectively contradicting the Leeds doctors. My old team-mates were full of the wisecracks you’d expect of bloody footballers: ‘That’s you here for ever now … They’ll build a stand around you … When are you moving in with [manager] Don Howe?’ And when I went back to playing for the Albion at Notts Forest I was met by an army of photographers. I suppose they were expecting me to drop down dead.”

Annoyingly I find myself asking Hartford: “How did you feel? … ” This is the standard inquiry of not just reality shows but news programmes. Everyone these days is more than happy to emote; in 1971 it wasn’t the done thing, not least among stoic Scottish footballers. But it seems a reasonable question for Hartford: he was a unique case, he possibly thought himself a bit of a freak, he could have feared for his health never mind his career and the psychological help which exists today wasn’t around for him.

“Was it a shattering blow? It’s a long time ago now but I don’t remember it being so. I mean, it was confusing and a worry for everyone around me, but footballers are pragmatic: I knew I was fit. Just before going up to Leeds I’d ran three miles round a golf course. In the cross-countrys we regularly did at the Albion I never finished lower than fourth. Leeds said I’d need an operation but that I should lead a normal life. Well, I’m still here and the op hasn’t been required. I see a cardiologist once a year and the last time he looked at the hole, which hadn’t got any bigger, he said: ‘That won’t kill you.’ And I didn’t have to stay at the Hawthorns – I got a move to Manchester City which was great for me, although I was told it only happened because Sidney Rose, the medical expert on the board, had been on holiday otherwise he might have put the kybosh on it!”

Hartford went on to marry Joy and, although since separated, they’ve stayed friends and he visits her every Friday when his three children, and a trio of grandkids, are also in attendance. Leeds wasn’t his only transfer melodrama. In 1979, Brian Clough took him to Forest as a replacement for Archie Gemmill only to sell him to Everton after just three games. “I still don’t know what happened there. I was surprised Archie had left because he was far from finished. Frankie Gray arrived at the same time and he was quickly charging up the left with Robbo and I suppose I was wondering how I was going to fit into the team. Before the next match Peter Taylor pulled me aside and said: ‘Funny old game, this. What would you say if I told you Everton were interested in signing you and we were willing to sell?’ Like a smart-arse I said: ‘In that case I’d like to meet with Gordon Lee.’ Then Peter hit me with the custard pie: ‘Good, he’ll be here in half an hour.’ The word was that Brian had suddenly decided he wanted Andy Gray who was going to cost £1.5 million so some quick sales had to be arranged. He was evasive when I asked him about this but told me: ‘Never mind, you’ll get your five percent.’”

Once again, Hartford was unfazed by a big move falling through. The hole-in-the-heart saga had probably steeled him against any further setbacks. He was certainly more than capable of standing up to Robert Maxwell who implored him to join Oxford United because very soon the tycoon would be running Manchester United. “I wasn’t sure that was going to happen and called him up to say I wasn’t coming. He wasn’t too happy. The phone went bang.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Forest farce came after Argentina where Hartford played all three games including Peru, with commentator David Coleman describing him as a “wholehearted player” – indeed Hartford was an ever-present under Ally MacLeod. He smiles wryly at the memory of that campaign, saying: “That was a great squad but we should have been told that the Peruvians had two wingers who could run Olympic-standard time for the 100 metres. Our hotel was supposed to be five-star. There was a swimming pool, right enough, but it had no water in it. When I sat on the loo in my room, drips fell on me from the floor above. That wasn’t water either.”

Tommy Docherty was ebullient while Willie Ormond could be daunted by the egos in his midst. “His famous line was: ‘The team’s the one in the Record and the subs are as listed in the Express.’” Hartford signed off for Scotland in the 1982 World Cup with the 4-1 defeat by Brazil. “When Jock Stein shook my hand at the airport I knew that was it.”

He treasures every cap, every memory, none more so than those tussles with England. As a prelude to the 1978 clash, Willie Donachie put through his own goal against Wales. “Mick Channon sent a telegram to our hotel: ‘Same again against us on Saturday, please.’” Ol’ Windmill Arms would still have been smarting from the previous year when the Tartan Army sacked Wembley after Scotland’s 2-1 victory.

I tell Hartford what Gordon McQueen, scorer of our first goal, said to me recently: ‘That was an easy header because Asa always hit a lovely free-kick.’ He laughs. “It was dead simple to find GoGo’s big napper. I can still picture him in the tunnel beforehand, seeming two foot taller than all the English boys, and telling us: ‘Let’s get right f****n’ intae them.’

“After the game our coach went past a pub where the Scots fans were struggling to hold each other up. One of them turned round, bent over and flashed his bare arse at us. He thought we were the English bus!”