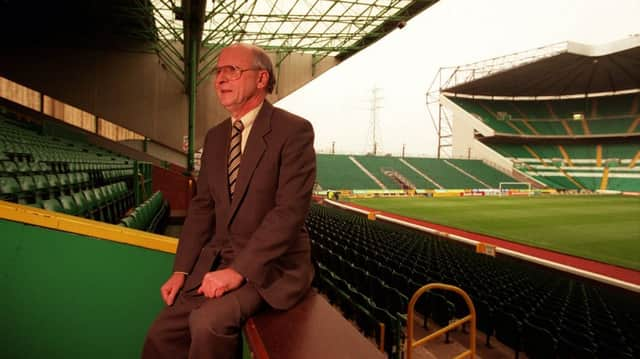

Glenn Gibbons: No point in McCann/Rangers parallel

This outbreak will be accompanied by an equally unsurprising rush to relate Rangers’ troubles in recent years to those of their great rivals two decades ago and to conclude that what the lurching Ibrox club require above all is a latter-day Fergus McCann.

The first of these two phenomena will be occasionally hilarious as the rewriting of the public and media perception of the Scots-Canadian proliferates; the second of them will be merely laughable.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo draw parallels between the circumstances that drew McCann across the Atlantic from Montreal in 1994 and those which caused Rangers to slither into administration two years ago yesterday is to dwell on a comparison that has no validity.

The would-be rescuer’s confidence in Celtic’s prospects of being restored to health and prosperity two decades ago may be detected in the fact that he attempted to bring his influence to the club several years before, only to be rebuffed by a hopelessly aloof board of directors. McCann had clearly recognised the potential for recovery, but it was most tellingly articulated by Len Murray, the well-known Glasgow lawyer, during an extraordinary general meeting of shareholders when the financial crisis was at its most dangerous.

Murray told the assembly that the club’s debt stood at around £7 million and that its basic value was £20,000; that is, 20,000 ordinary shares at £1 each. “No company in the history of business,” Murray concluded, “has survived liabilities amounting to three hundred and fifty times its capital value.”

The lawyer, of course, did not mean that the debt had become unmanageable, but that the club was ludicrously undervalued. This was due to the anachronistic, scandalous regulations of the private limited company, which decreed that shares could only be traded with the blessing of the directors and that board members should have first refusal on any that became available. Most significantly of all, the shares were not allowed to “float” to their true value, as a result of which directors were able to purchase them for around £3 each.

They were, naturally, allowed to soar to their proper price when McCann came buying. Bulk holders such as Michael Kelly, Chris White and David Smith commanded around £300 per share, a form of hardball that left McCann understandably resentful over the disappearance into their pockets of funds that could have been used in the resuscitation of the business.

What mattered most to McCann, however, was that the outdated management of the club had created a mess in which crowds were down to well under 20,000 – in one or two instances, struggling to reach five figures – and that the previous regime had insisted on a limit of only 7,000 season tickets, on the preposterous basis that “season tickets are more trouble than they’re worth”.

It is a measure of the persuasiveness of McCann’s personality and his formal business plan that Dermot Desmond, the Irish money machine who had no previous interest in football, should be so readily recruited as a major investor. The two men were introduced by Robert Lee, then a young professional golfer and now a pundit on Sky Television, who told Desmond that “there’s somebody here I think you should meet”.

In a lengthy conversation in his suite at the Dorchester Hotel in London a couple of years later, Desmond told me that he had taken one look at McCann’s business plan and asked him one question: “How much do you want?” When he was told that taking £4m worth of stock in the upcoming share issue would be advisable, Desmond asked a second question: “Do you want any more?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Irishman added that “it was clear from the start that Fergus would make a success of it. There was no way this was going to fail. I told him that if he wanted any further investment down the line, I would be very happy to oblige”.

McCann not only built a new, 60,000-seat stadium, but finished up with 53,000 season-ticket holders, a miracle of marketing that brought full houses to Celtic Park for opposition teams who would, in the past, have lacked the drawing power of a Christmas cracker magnet.

The single most significant difference between the commercial naivety of clueless directors that brought Celtic to its knees and the appalling financial excesses of David Murray that led eventually to Rangers’ liquidation is that the latter club was left with little or no scope for recovery. Rangers hit the wall when they already enjoyed capacity crowds, record season-ticket sales and maximum annual turnover.

These details are among a number of reasons why it is impossible to imagine a conversation and a transaction between two possibly life-saving investors in present-day Rangers such as took place between McCann and Desmond 20 years ago.

Far from thriving on new-found revenue streams, Rangers are haemorrhaging money because they have no credit lines, the need to pay for services and supplies on delivery being the most damaging consequence of their previous actions in leaving creditors seriously disadvantaged.

Fergus McCann once agreed that “it would have been cheaper to go into liquidation, but it would not have been the right thing for Celtic to do”. It was a nifty seizure of the moral high ground, but, given his record, he should be credited with the nous also to have realised that, in the long term, administration and liquidation would have been an unacceptably expensive business.