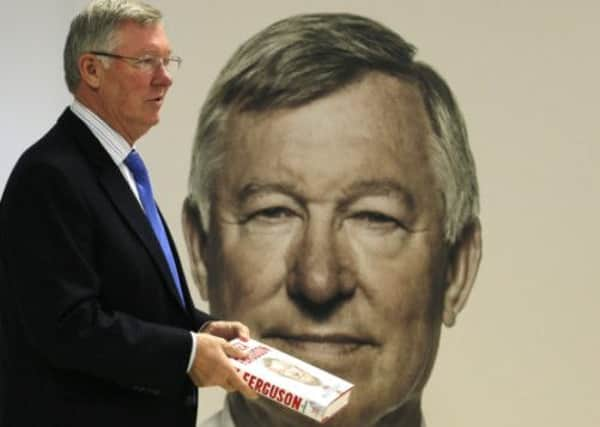

Alex Ferguson’s book proves to be thought-provoking

My Autobiography

Alex Ferguson

Hodder & Stoughton, £25

A token, early chapter reflecting on his Govan roots, followed by a jolt forward to Christmas 2001 and a provocative rifle through the subsequent 12 years does not amount to the story of a man’s life.

Still, this much-publicised book, produced to mark his retirement from the game after 27 years as the manager of Manchester United, is none the worse for that. After all, the minutiae of his life and work have been detailed in two previous efforts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFerguson’s first book, A Light in the North, documented his days in charge of Aberdeen. His second, Managing My Life, was a more comprehensive account of the journey from his boyhood in Glasgow to victory in the 1999 Champions League. My Autobiography effectively updates that work, setting the record straight in typically forthright fashion on the successes, failures and controversies of that period.

Thanks to a pre-launch press conference, the tastiest parts have already commanded nationwide attention. Ferguson’s belief that David Beckham “chose” fame over football. The row that led to Roy Keane’s departure from Old Trafford and the circumstances that caused Wayne Rooney to demand a transfer. However subjective and self-serving, Ferguson’s views are compelling.

But, as Paul Hayward, the ghostwriter, pointed out the other day, it is more than just a news tornado. It is a football book. Even those who pored over every headline-grabbing extract will enjoy the rest of its frank and enlightening take on the last decade.

Ferguson offers good, knockabout stuff on his opponents down the years. Players, teams, managers are all given the treatment, some of it playful, some of it not. With Rafa Benitez, it is personal. The former Liverpool manager is clearly a man for whom he has no regard. Ferguson more or less rubbishes the Spaniard’s achievements, with a Champions League victory reduced almost to a footnote.

Ferguson is at his most insightful when it comes to players. He has a clever knack of capturing, in anecdotal form, what is unique to each of them. He describes Ole Gunnar Solskjaer as the best finisher he worked with. The Norwegian substitute would studiously use his time on the bench to identify his opponents’ weakness. Then, when he was called upon to play, he exposed it. Paul Scholes was so talented that, every time a team-mate interrupted training to go for a pee in the woods, he would hit him on the back of the head with a long-range pass.

Despite his reputation for mind games and the infamous hairdryer, Ferguson also has an acute appreciation of the game’s finer points. Notice, he says, the way he taught Cristiano Ronaldo to lengthen his stride as he closed in on goal so that he was more composed in the act of shooting. The Portuguese striker, he says, was the most gifted player he managed, although Scholes wasn’t far behind.

Ferguson is obsessed with the so-called “class of ’92”, the group of homegrown players who went on become the club’s heartbeat. In particular, he returns time and again to the contribution, so selflessly offered, by Scholes, Ryan Giggs and the Neville brothers. When Phil Neville was invited to Ferguson’s house to discuss leaving Old Trafford – a meeting arranged by Gary because Phil did not want to appear disloyal – his wife sat outside in the car, crying her eyes out.

Full though it is of tales such as these, it is not a polished product, at least not compared to Managing My Life, which was co-written by Hugh McIlvanney. My Autobiography leaps back and forth between subjects in haphazard fashion. And the repetition of facts and opinions can be irritating.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the other hand, it rings true. Hayward is an award-winning journalist, capable of much better prose but he resisted the temptation. The result is an easy, page-turning read that has faith in Ferguson’s own words. After all, he is a man with a hinterland, a keen intellect and an interest in history’s great dictators.

Control is the recurring theme. Ferguson’s mantra is that no player should ever be bigger than the manager, which explains the departures of Beckham and Keane. Every manager, he says, needs a good chairman, by which he means a supportive one who does not interfere. Even the media have to be controlled. He held press conferences first thing in the morning when a briefing by the club’s communications department was fresh in his mind. He also took advice on his body language and banned reporters who asked the wrong questions.

To have control, you need power, and United certainly gave him that. In the introduction, Ferguson thanks Bobby Charlton and David Gill for giving him the time to build not just a team, but a club. So successfully did he repay their faith in him that his reputation now transcends football. In politics, he has advised Tony Blair, socialised with Angela Merkel and been shown around the White House. But, with that power came occasional loneliness. Ferguson admits that, despite his workload, there were times when he would sit in his office, waiting for someone to knock on the door. They never did. They assumed he was busy. Or that he did not want the company.

He wonders if Blair also experienced that strange vacuum at the heart of leadership. “Sometimes you would give anything not to be alone with your thoughts,” he writes, which is perhaps another, more subtle explanation for this candid volume.