The fight of Muhammad Ali’s life

BILL Siegel was eight years down the road of making his film about Muhammad Ali when his producer and researcher walked into the edit room in January this year and told him she had something he needed to see. It was a clip from the Eamonn Andrews show from 1968. In the studio was the then famous American television presenter and political commentator, David Susskind, and peering out of a small black and white television on the studio floor was Muhammad Ali, speaking live from Chicago.

“I’d been working on this Ali film for eight years but, in truth, the journey to that point had taken me 23 years because I had worked on another Ali movie in 1990,” says Siegel, the director the newly released The Trials of Muhammad Ali. “And, despite 23 years, I had never seen this clip of Susskind and Ali. As soon as I saw it, we all looked at each other in the edit room and said, simultaneously, this is the beginning of the film.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAli was banned from boxing at the time. He was one of the most hated men in America for refusing to fight in the Vietnam War and for espousing the word of the Nation of Islam, a separatist group that believed that the white man was evil and that anybody who spoke ill of the Nation’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, deserved to die. Susskind’s words are powerful and redolent of the time. “Well, I don’t know where to begin,” he says, calmly, when asked by Andrews what he made of Ali’s stance of conscientious objector on Vietnam. “I find nothing amusing or interesting or tolerable about this man. He’s a disgrace to his country, his race and what he laughingly describes as his profession. He is a convicted felon in the United States. He has been found guilty. He is out on bail. He will inevitably go to prison, as well he should. He’s a simplistic fool and a pawn.”

Ali gently bows his head. “The image is of Ali trapped in this little black and white television in America,” says Siegel. “He’s not allowed to leave the country so he can’t sit across the couch from Susskind in London. He’s imprisoned and helpless. And, in the next clip, we cut to 2005 and President Bush is putting the presidential medal of freedom on Ali. That’s a hell of a journey.”

The world is full of Ali films and documentaries. There is so much out there and yet the depth of this latest film is compelling.

We’ve had When We Were Kings which was quite brilliant. We’ve seen Muhammad Ali: Through the eyes of the World and that, too, was exceptional. What makes The Trials the equal of those epics is the footage that it has found that shines more light on what it was like when Cassius become Ali.

It’s not a boxing film but it’s definitely a fight film, the fight in question being the greatest of Ali’s career, the one that saw him take a stand on Vietnam and run the risk of bankruptcy or death.

Siegel is an Oscar-nominated director – for his documentary film The Weather Underground in 2004 – and a chronicler of Ali’s life. What we see here is the brightest cinematic torch shone on Ali’s politics of the 1960s, his uprising against racism and his unshakeable objection to war. His membership of the Nation of Islam and his evisceration by commentators is pored over through footage that makes you gasp.

Do we need another Ali film? The truth is yes, we do, when it’s as compelling as this one, when it zooms in not on the boxing – there isn’t a whole lot of that – but on the struggle, on the contradictions, on the hate Ali was subjected to and the hateful messages he sent out as a member of the Nation of Islam. And how he moved beyond all of that.

The film was a long time in the making because Siegel found it tough to convince potential funders that the world needed to revisit another slice of Ali’s life. Every facet of his story has already been broken down and analysed. From the stolen bicycle that brought him to the gym as a kid to avenge the thieves who pinched his wheels in Louisville to the Olympic Games of 1960, from shaking up the world against Sonny Liston in 1964 to the Phantom Punch in the rematch in 1965, from Joe Frazier to George Foreman, the Fight of the Century in Madison Square Garden, the Thrilla in Manila and onwards to the Rumble in the Jungle.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmerica versus Muhammad Ali, the court case that saw him banned from the sport for three and a half years on account of his stance on Vietnam, has been covered in print, but not really in film. Not in this depth.

“If the film is doing its job then it should be more about us than it is about him,” said Siegel. “What I mean is that the capacity to find yourself and take a truly moral stand exists in all of us, just as it existed in Ali when he said he was not going to Vietnam. Too many of us let life go by, but it’s there for the taking if you want it. One of Ali’s greatest statements is that he didn’t have to be who we wanted him to be, that he’s free to be who he wants to be. I hope the film shows him emerging from Cassius Clay and discovering his identity and, through that identity, discovering what kind of human being he wants to be in the world. That was a very painful and ugly journey.”

The Nation of Islam was a sect that was led by a grandson of slaves, Elijah Muhammad, born in rural Georgia in 1897. Elijah believed that the white man was evil, that integration of the races was a sin. “Separatism is the only solution,” was his creed and it became Ali’s creed. “I don’t hate nobody and I ain’t lynched nobody,” Ali said in the late 1960s. “We Muslims don’t hate the white man. It’s like we don’t hate a tiger, but we know that a tiger’s nature is not compatible with people’s nature since tigers love to eat people. So we don’t want to live with tigers. It’s the same with the white man… we don’t want to live with the white man, that’s all.”

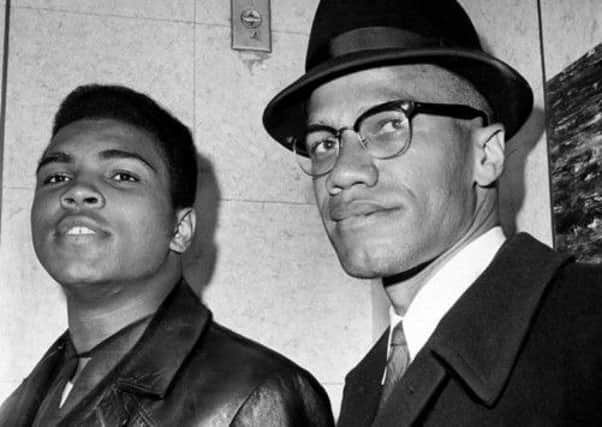

One of Ali’s greatest influences in the mid-1960s was Malcolm X, a fellow member of the Nation. Malcolm grew to see through Elijah Muhammad as a senile old man surrounded by malevolent protectors and he abandoned him. Soon after, Malcolm was assassinated. Ali stuck with Elijah but drifted away from the teachings over time.

One of the most intriguing parts of Siegel’s movie is when he talks to the Nation’s great figurehead, Louis Farrakhan, who carries on the teachings of the Nation, which Ali outgrew. “It’s hard to find anyone now who dislikes Ali,” said Siegel. “It’s not impossible, but it’s hard. There are still some who will call him a draft-dodging n-word, but he means so many different things to so many different people and that continues to evolve. For example, minister Farrakhan. When I interviewed him he said nobody had ever interviewed him about Muhammad Ali before, which I found extraordinary, given that he was around Ali all the time in those days. Farrakhan was the most intense interview I did, but he was ready to talk. His people gave us 20 minutes and, once we got going, he gave us an hour. In the film he says that Ali was constantly evolving, constantly changing from the narrow view of the Nation of Islam to the broad universal view of Islam in its fullest development.

“Ali left Farrakhan’s beliefs behind along the way but the minister has no resentment that Ali grew past him and that narrow race-based ideological view that the Nation espouses.

“Farrakhan remains a polarising figure in American society but he’s not as polarising now as Ali was then. I think you in the UK understood Ali before some of us in the States. The appreciation of him – the love of him as it is nowadays – didn’t happen overnight. We’re talking about modern American history here, through the prism of a heavyweight champion. The country came to a reckoning that the government had led them down a horrible path in Vietnam and that Ali was right when he didn’t go to war and we were wrong. They started protesting about the war and at the same time the black freedom struggle was happening and Ali was at the crosshairs of it. Over time, it became more and more obvious that he had done the right thing and that we had done the wrong thing.”

Siegel’s exploration of the 1960s Ali is now rolling out across American cinemas. Ali’s family co-operated with it, have seen it and have been moved by it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The film is going to a number of different countries but there’s nothing organised in the United Kingdom yet, but it would be good to show it there,” said Siegel.

Ali is 71 years old. He fought his first professional fight 53 years ago. Next year will mark the 50th anniversary of him winning the heavyweight championship of the world for the first time and the 40th anniversary of the Rumble in the Jungle.

The fascination never ceases because the story is the greatest. The Greatest.