Sixty years of Rewilding with the UK's most trailblazing conservationists

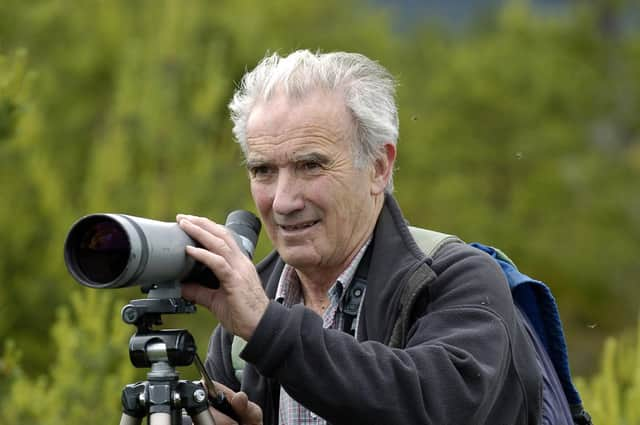

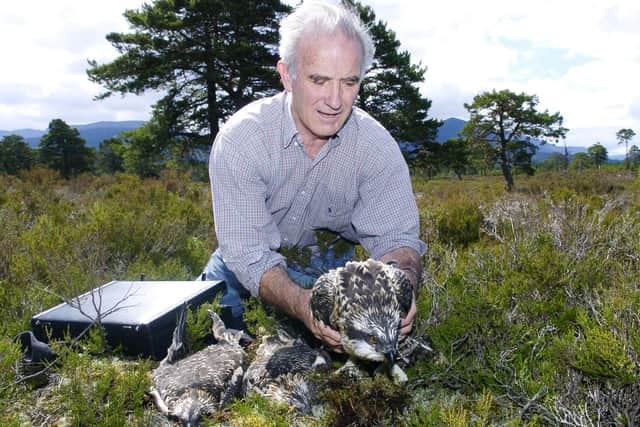

Roy Dennis lives surrounded by his life’s work. Based in Moray, just south of Forres, the ornithologist and wildlife consultant is close to the River Findhorn and Bay, nowadays a hot spot for feeding ospreys, one of the species he helped reintroduce and champion in Scotland. It’s a place he has known since coming to monitor and research ospreys since 1968.

“It’s fantastic. When you’ve translocated ospreys and then one comes back from Africa to where you want it to be, that’s just special,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe magnificent birds are just one of the species the man regarded as the UK’s pre-eminent conservationist has been behind the reintroduction, relocation and recovery of in Scotland and elsewhere. Along with sea eagles, kites, goldeneye, red squirrels and beavers, they are flourishing as Rewilding becomes more and more popular, not least because of the economic advantages - sea eagles and the tourist pound are worth £5m a year to the Isle of Mull and £3m to Skye. And if Dennis’s hopes are realised, lynxes, wolves and even bears could one day be seen again in Scotland.

Over his 60 years working in the field in the Highlands and Islands, as bird warden on Fair Isle, as a conservationist with the RSPB and then for his own foundation, since 2016 The Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, he kept filed books and diaries. With the approach of his 80th birthday last year, he decided to write it up into a book and the result is Restoring the Wild: Sixty Years of Rewilding Our Skies, Woods and Waterways.

“I decided to do the kind of introduction,” he says of “Then maybe in a year or so I could write up the rest.” He laughs.

A fascinating and entertaining book, it follows his own journey from childhood in Hampshire to that of the birds and animals he has worked with - the sea eagles that were flown from Scandinavia to Scotland on RAF Nimrods, the ospreys, eagles and kites, the red squirrels that crossed mountains and swam across rivers and the beavers that are spreading across our waterways and rivers.

There are tales of talking solely in bird sounds out in the woods with an expert in Scandinavia, getting up close to wolves and bears from the Yukon to the Europe, being dangled from a rope in sea rescue exercises in exchange for RAF lifts and marvelling at red kites soaring over the M25.

One of Dennis’s most successful reintroduction projects has been with red kites, a bird that was so plentiful during the reign of Henry VIII that they could be seen on the streets of London.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“When we brought them back there was a lot of opposition but there are four or five thousand pairs now in Britain. A few years ago when I was going down to the Isle of Wight for the white-tailed eagle project, coming round the M25 there’s a kite above me. When I saw that I thought, we did something great there,” says the rewilder who picked up an MBE for services to nature conservation in 1992 and the RSPB Golden Eagle Award for being the person who had done most for nature conservation in Scotland in the last 100 years in 2004.

However popular the birds, there is still reticence over the reintroduction of wolves and lynx in Scotland, something he attributes to our being an island.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The chances of seeing those animals here are zero compared to mainland Europe. I say to people, ‘you go on holiday to Spain, Portugal, Italy, and there are wolves all over the place, and they say, ‘Yeah well I never saw any’, but if they were in Scotland, you wouldn’t see them either. You might hear them howling on an evening, that’s all. It was useful that I’d seen wolves in Greenland and places in Europe. I wasn’t frightened, not at all. I was frightened in the Yukon when I looked out my tent and saw a grizzly bear though.” He laughs.

What did he do?

“Kept really quiet.”

But is Scotland big enough to bring bears back?

“Yes, there are brown bears in Northern Spain, 600 to 700 nowadays. Our brown bears are not as aggressive as those in Northern Canada and America. They wouldn't be challenging. But it doesn’t help when you say ‘well there are far more people killed by pet dogs’.

So is it the farmers and landowners who are scared, because of their livestock, rural residents or the general public?

“Well, with wolves, farmers are about protecting their livelihood from sheep, but they know what to do - shoot them or get compensation. I think it’s more ordinary people, ‘would we be safe if we went for a walk, would our children be safe when they were canoeing down a river?’ I think there are genuine worries and the important thing for us as conservationists is to really know these species and be respected as someone who is sensible. Quite a few conservationists can be a bit wacky.”

Has he ever been called wacky, or obsessive?

He laughs. “No.”

Red Squirrels are one thing, who doesn’t love watching a red squirrel in their garden bird feeder? But does he really see it happening with wolves and lynx, maybe even bears?

“The lynx, yes, I can’t see why not. I think wolves and bears will be much more difficult. It will happen one day, but there would need to be a way they would remain in the main Central Highlands.

Advertisement

Hide AdFor Dennis it’s political support that is crucial, a factor in reintroducing sea eagles back to the Isle of Wight.

“I think the major reason for that was Michael Gove, the environment secretary, had a 25-year plan for England and Wales that included seeing the white-tailed eagle back, we were knocking at an open door. I don't think we've ever had that sort of political steam behind us in Scotland. For all these more difficult projects you need a politician who is prepared to stand up and say we want this to happen. If they do, there are people who can help.”

Advertisement

Hide AdSo in the current crop of Scottish political leaders, does he think there are any likely to champion rewilding?

“I think there are in the new government and they could. I wish they would. Public opinion is pretty positive towards lynx and very positive toward beavers. There are concerns from farmers and the like, but those have to be put in perspective with the greater social good and social wishes.”

Would lynx and wolves have to be in an enclosed space and require management?

No lynx can be just anywhere from Perth northwards.

And wolves?

At the present time that would be much more challenging to decide how to do. There are landowners who have backed it - Paul Lister, for example, wanted them in a big enclosure, but people didn't like that.

If the animals have to be in an enclosure, is there any point, is that rewilding?

I don’t like it, but you could fence in an area maybe 20 miles by 20 miles, and that's not really fencing. In some ways the most effective fence is the amount of buildings between Glasgow and Edinburgh that stops anything coming from the North. Often there are already major fences, but not in a traditional way. There are massive areas fenced off for forestry or all sorts of things. For animals to cut across country nowadays is much more difficult because of man made barriers.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAnd yet they do, for example Dennis and his colleagues discovered that the diminutive yet determined red squirrel can scale mountains and swim across rivers if they have to.

“We were pleasantly surprised by that. The squirrel was all but exterminated in Scotland in Victorian times or earlier and then various landowners, but particularly Lady Lovat at Beauly near Inverness, decided to bring them back. They exploded and went everywhere and I think they walked. When numbers build up, they're very territorial and fight like heck, and they thought it's better to walk over this mountain to the next wood than stay here and get beaten up all the time. It was a natural dispersion.”

Advertisement

Hide AdFor Dennis rewilding started when he was a child, first with a jackdaw and shelduckings, then later as an adult with with a red squirrel orphan Timmy, who occasionally lodged in his jumper and went with him to the pub, then one day walked off into the woods at Loch Garten and never looked back.

“When I reared those sorts of things I always had them part in the wild because I didn’t want to keep them as a pet, so they could run off when they wanted. Then they get to the stage where they just decide not to come back, and that’s good. But the jackdaw, I think I did think it was a pet.” He laughs.

“The value of that is - and it’s something children can’t do now, because it’s illegal or it’s not socially acceptable - learning how to identify a healthy animal or an animal that’s dying. Are their eyes bright? When you found a baby rabbit and looked after it and suddenly one day that its eyes are a bit cloudy, your mum would say ‘that’s going to die tomorrow’. You need to know that things die.

During lockdown Dennis and his wife Moira bought six hens that his 12-year-old daughter looks after.

“I think that's good because she sees some lay very well and she can make a bit more pocket money, while others don’t. And one day one of them will die. And that’s just part of life.”

“I worry that nowadays young people don't get so much of that opportunity. It’s difficult, field work means taking children in the countryside. When I went as a kid, oh god, the people looking after us let us do anything - now they would be prosecuted.” He smiles.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn Dennis’s view something has been lost and we need to compensate.

“From age seven my little gang could wander off into the woods and our parents didn't worry too much. Now, sadly, parents are much more worried, so the distance you're allowed free rein is much shorter. You need to make up for it. How do we teach children to know nature, to be safe in nature?

Advertisement

Hide AdDennis’s own brood of four had the advantage of a father involved in rewilding, although they didn’t all follow in his footsteps up trees and into hides for a living.

Talking to Dennis and reading his book, time and again there’s an idea for a project and Dennis plants seeds, but it can take a decade or longer to germinate. Is patience the most important thing in Rewilding?

“It is. And chance. You can’t do anything about chance. You do your best and you hope. At Poole Harbour in Dorset, where we’ve taken these ospreys, a female recognised there were young ones so came back ready to breed in 2018 but there was no young male suitable. The next year one came back but was too young, and we thought next year will be perfect. He never arrived - maybe ran into bad weather and was killed. This year she’s back again, but a young male arrived too late to breed. So you hope both of them survive and come back next year - and that will be the first successful breeding.

“You’re trying to get it as close to perfect as possible, but there’s still a lot of chance. When you get first breeding of a new population, then you know that things are going to go. It takes time.”

At 81 does Dennis think he will get to see wolves and lynx in Scotland?

“I always said I’d love to see those before I die, so it’s an encouragement to live.” he laughs.

Advertisement

Hide AdLooking to the future Dennis is energised by the younger generation’s awareness of climate change, how they are infused with a sense of urgency that may be missing in older people. On top of this there’s the shot in the arm delivered by the global pandemic.

“I think the issues for young people are much greater and I believe they should have much more say about politics. I got into trouble recently because I said young people should be able to vote from 14 and when you reach 60 you lose your vote - you’ve had your go.”

Advertisement

Hide AdI point out that this would mean he wouldn’t get to vote himself.

“Yeah, but they can give advice,” he says and smiles.

In terms of favourite projects over the years, it’s always whatever he’s working on right now.

“At the moment I’d say the white tailed eagles in England are probably the most interesting and exciting thing we’re doing. If we were suddenly having lynx in the country, it would be that.”

In terms of wider public opinion what have been the most popular projects? Red squirrels, beavers?

“Lots and lots of people are really interested in ospreys,” he says, “Maybe because there are ospreys all over the country now and webcams.”

Check out https://scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/things-to-do/watch-wildlife-online/loch-of-the-lowes-webcam/ to see the chicks on the nest right now.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Red squirrels are popular too, people are thrilled to have them into their gardens, now up in Ullapool too. It’s important you have populations big enough that some can go into people’s gardens.”

What does Dennis think is the best way to change people’s minds about the reintroduction of species?

Advertisement

Hide Ad“To be recognized as knowing what you're talking about and not telling people what to do, to work with them and in the end regard them as friends. Work in a way where they don't think of you as just being a bloody menace. It’s the human touch. I love having a crack with keepers, shepherds, farmers and landowners, going into the house and having a cup of tea. I don't just talk about birds or mammals, I love to hear how they're getting on with shooting deer or catching salmon or clipping sheep, and you can also talk about the issues.”

Would you say you’re optimistic about the future of rewilding?

“You have to be. Humans are amazingly capable of doing things. If you think of the money spent on this pandemic worldwide, that’s the sort of money that should be spent sorting out problems with the environment and climate.”

“There are young people now who really understand this stuff. The people who need educated are the politicians, councillors and business executives. But we are very pleased so many think about these things. When I go around now and hear how many big estates that used to be just killing stuff have decided to go into rewilding, or to go into regenerative agriculture, it’s very encouraging,” says Dennis.

“In the last 20 years there's been a tremendous change and what is going to push it even further is that young people are now involved and worried about the future of the planet. The things we do now are much more accepted.”

Today Dennis is involved in exporting white-tailed eagles from Scotland to England and about to start collecting 12 young birds from the Hebrides for the next year's Isle of Wight project, which has exceeded expectations.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“People said, ‘There's no room in southern England for eagles’, but they’re fitting in extremely well. There's a huge amount of food: rabbits, hares, fish in the sea and lakes and introduced Canada geese everywhere. Now people in lockdown are writing saying ‘we're stuck in our gardens, looking up and this monster bird flies over at about 1,000 feet and it's made not just our day, but our year.’”

Over the years Dennis has seen the opponents of rewilding change along with their opinions.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“That used to be gamekeepers, farmers and landowners, but now I have friends who say ‘I love what you're doing but when I was young I didn't like it at all.’ And young people take over farms and crofts and realise there may be more money in ecotourism than in rearing sheep.

“If you're suggesting new things you'all always get opposition. For example, we would like to see the lynx back and people will say, ‘Well the reason we haven't got them is because we got rid of them. But why did they get rid of them? Not because they were nuisances, probably because they were trapped for fur. The same with beaver. There's no doubt they make rivers and wetlands much richer for fish, as well as all the other invertebrates and birds.

“The Victorian attitudes of kill everything that's not what you want, which is grouse, salmon, pheasants and deer, those days are going.”

Restoring the Wild: Sixty Years of Rewilding Our Skies, Woods and Waterways by Roy Dennis is published by William Collins, in hardback, £18.99

The Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation (www.roydennis.org)

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.