Scottish independence may seem a good idea amid 'post-war' euphoria of Covid pandemic's end but history warns against unrealistic dreams – Alastair Stewart

Churchill and his former Labour deputy Clement Attlee flew back to the UK to hear the election results, of which Churchill anticipated a landslide in his favour.

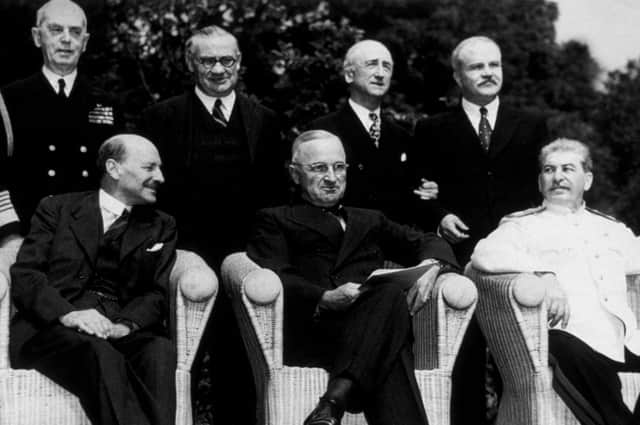

And why not? The first general election in ten years seemed like a sure thing for Churchill. He was ‘the man who won the war’. Churchill expected triumph and a mandate to continue the war in the Pacific. US President Harry Truman and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin expected to see him within days.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe results of the July 5 General Election were not declared until the 26th. But it was Attlee who flew to Berlin on July 28 to rejoin the conference as head of the British delegation. Labour had won a landslide of 393 seats to the Conservative Party’s 197 – a net gain of 239 seats with Labour receiving 47.7 per cent of the vote.

Covid-19 has called the bluff on anyone who has ever used a war analogy. The global stakes, the uncertain outcome, the restrictions and the genuine national undertaking – this is the real deal. If leadership and endurance are drawing comparisons, the aftermath needs to be considered too.

And that's the comparable juncture we find ourselves at in Scotland. Will we want more of the same when the pandemic is all over or a different kind of future? Does Scottish independence offer the kind of change people grasped at the end of the war in Europe?

By 1945, the public was exhausted and the country bankrupt. Pundits, pollsters and politicians all failed to factor in the desperation for a different vision of the future.

Attlee offered a free National Health Service, a mixed economy with full employment and "cradle to the grave” care for British citizens. And Attlee, the “sheep in sheep's clothing” as Churchill called him, was the man to bring it about.

Churchill's popularity did not translate into support for his party. Most agreed he led the nation to victory, but many doubted the Conservatives – in power, in some form or another, since 1931 – would offer material change after the war.

Churchill was given "the order of the boot" because his post-war focus was international. He was a man who shaped significant events and struggled with domestic policy (an irony given that Churchill, alongside Herbert Asquith and David Lloyd George, was a principal driving force behind the Liberal Party's welfare reforms of 1908–1911).

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon will be hailed as the person who 'led' us through the pandemic. The SNP are on track for a majority in May 2021 elections. There's been a streak of polls in favour of Scottish independence. There is an appetite for change, but it needs to be tempered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhatever your views on it, the disruption would be historic. Its supporters dream of a smooth transition, bucking the trend of every other state disintegration in history, to say nothing of Brexit. Attlee’s radical post-war agenda was within the limits and opportunities of the state – independence on the back of the pandemic could be financially devastating, if emotively tempting.

Even Attlee's revolutionary tenure ended by 1951. The party had weathered storms and set a course, established the post-war consensus, but questions of rationing and further nationalisation, coupled with Labour in-fighting, finished the government. Churchill was returned to power by a slim majority. There wasn't another Labour government until 1964.

Attlee's tenure is a sharp warning that the hopes and dreams of people at end of a crisis will inevitably disappoint. If the party that cemented the welfare state cannot make people happy, no one will. Unrealistic hopes and dreams on the back of a crisis are a recipe for disappointment, if not disaster.

If Brexit is a template, Scotland would face years of negotiations that could dilute how people understand what independence means. There is nothing to preclude the emergence of right-wing governments in the future. There is nothing to guarantee full employment, the eradication of poverty or full equality – worthy ambitions, but pipe dreams without an articulate plan.

Policy and state-building are two different things. The lesson of the post-war Labour government is there can be a radical policy change without the need to start again. Independence would be state-building in all but name and would not necessarily redress the imbalances and problems flushed out by the Covid-19 pandemic.

By the end of the war, attitudes changed, as did expectations on what the state can and should do. If the government can mobilise every man and woman to serve a war effort, it should be able to look after them too.

The massive support packages for furlough and business, to say nothing of the need for huge NHS investment, are priorities. These are issues that should be championed, but as the pandemic draws close, we should seriously ask what the most realistic, not the most emotional, methods are to make lasting change for the better.

The pandemic is, god willing, the closest as any of us will come to the misery of total war. We most now balance our 'post-war' euphoria with a tempered assessment of how to make a better tomorrow.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlastair Stewart is a freelance writer and a public affairs consultant. Read more of his work at www.agjstewart.com and follow him on Twitter @agjstewart

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.