Joe Wilson: Are we desensitised to photography?

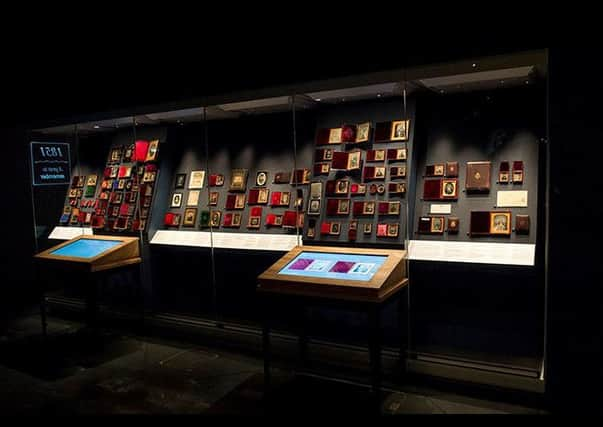

Standing engulfed by the spectacular display of faces and landscapes at the National Museum of Scotland’s Photography: A Victorian Sensation, I am struck by a sensation of my own. Not since I deleted my Instagram account, now two New Years resolutions ago, have I been party to such an intensive timeline of portraiture. There are no filters or fancy effects here, though. For many of these people this was the only photograph of them ever taken, and as such they have been treasured and cared for by their owners to the point where they have made it into the collection of a museum over a hundred years later. This is why the inevitable “your selfies displayed here” interactive at the end of the exhibition actually sits a little uncomfortably. After marvelling at a centuries’ worth of lovingly preserved photography, I was then expected to take one of myself and then exit through the door to the left, never to see it again.

The modern photograph has mutated into a very temporary possession. Photographs these days are lost all the time. These can be unexpectedly through computer hardware malfunctions or intentionally, such as self-destructing Snapchat images or, for example, purposefully deleted for certain emotional reasons. The latter is not a new phenomenon. A fellow student I was studying alongside for my masters degree once revealed his unusual hobby of collecting old daguerreotypes where people’s faces had been scratched off. Despite their defacement, the continued physical existence of these photographs actually makes them doubly intriguing as artefacts. I was always taught to analyse historical source material using the “Five Ws” method; “what is it, and when was it created?” “who created it, and why did they do so?” and “what does it say?” My colleague’s collection, however, had the benefit of possessing a 6th required “W”: “woah, what on earth happened next?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe suggestion here is not that we retain every single one of the millions of photographs that are taken every minute of the day, nor that instead of deleting pictures of undesirable people that we aggressively scribble over their faces in MS Paint. It is simply that we take better care to preserve the important images. From the 50 or so years worth of portrait photographs at the National Museum of Scotland’s exhibition, you can learn a lot. For example, for many subjects this was a rare opportunity to have their image captured, and these images provide us with a fascinating insight into the evolving ideals of fashion, manners and etiquette of the time. Nowadays, with fashion moving so quickly and the ability to take photos all the time, that “selfie” of someone in last month’s “get-up” just gets deleted and replaced, meaning future viewers will have no real sense of a community’s changing attitudes to trends on the social level that we can examine in our 19th and 20th century counterparts.

Photography: A Victorian Sensation claims that in 2015 an average of 70 million photographs are uploaded to Instagram every single day. One would assume the proportion of this that includes portraits and “selfies” is quite high, most of which are destined merely to tumble endlessly down a timeline into forgottenness. A little down the road at the Scottish National Gallery, the David Bailey retrospective, Stardust, provides no greater proof that quality trumps quantity every time. Not only are his images iconic, but some of them – such as one of Jack Nicholson and a young Johnny Depp – are some of the most iconic photos of those individuals. These are portraits that are valued, were treasured, and are enriching to the viewer because of it.

The fame of Bailey and his subjects make these portraits exponentially valuable, but there are more than just famous faces on show at Stardust. The exhibition displays work from his travels in places like Nagaland, Sudan and Papua New Guinea. In these pictures, there are no recognisable figures, simply people, who like those on display at the National Museum of Scotland, may well be experiencing being photographed for their first or only time. Regardless of the name behind the camera, you have portraits worth treasuring because they are valuable historical sources, with much to teach the world about other countries, their customs and often their plights.

To describe the “your selfies displayed here” section of Photography: A Victorian Sensation as “uncomfortable” was not a criticism, it is important for museums to provide thought-provoking content. This is what it provided for me. When exploring the exhibition, you truly feel that photography in the late 19th century was a sensation, and people valued their pictures to the point where they were framed in lockets, crafted into jewellery or displayed in elaborate albums. But most importantly, they were simply preserved. We live in an age where people are desensitised to the value of photographs. In Photography: A Victorian Sensation, the National Museum of Scotland has curated the memories of an entire generation. Additionally though, they also inspire a concern that our current, increasingly self-conscious generation has such a wealth of means to curate its own memory to reflect its present concerns that it could deprive future generations of any genuine sense of its past.

• This edited article was originally posted on I Think Of Icarus, a Scottish museum blog run by Glasgow-based Joe Wilson. http://ithinkoficarus.com/