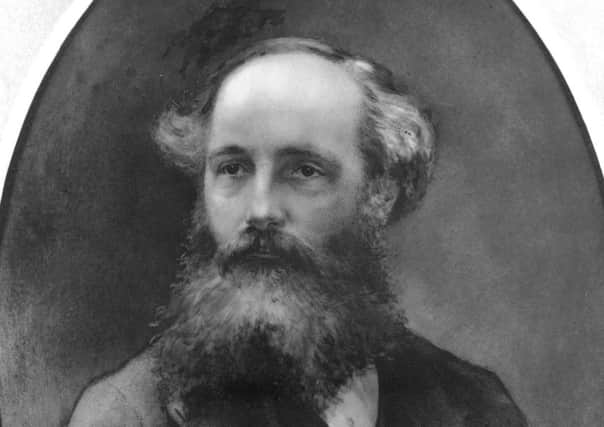

James Clerk Maxwell: The Scots genius in love with numbers and nature

The Academy was a relatively new school, which had been open for just 18 years when Maxwell first attended. It was set up to compete with the classical education provided by English public schools.

As such, it had a focus on giving its pupils independence and hard discipline alongside a rigid curriculum that focused intensely on the classics with perhaps a spot of maths; there was very little science.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the father of the founder of the Scouting movement Robert Baden-Powell commented in 1832: “Scientific knowledge is rapidly spreading among all classes except the higher, and the consequence must be, that that class will not long remain the higher.”

Having such a limited curriculum seemed to be a mark of pride in the public schools. John Sleath, High Master of the prestigious St Paul’s School in London during the early part of the 19th century, wrote to his parents: “At St Paul’s School we teach nothing but the classics, nothing but Latin and Greek. If you want your boy to learn anything else you must have him taught at home, and for that purpose we give him three half-holidays a week.”

This was a period when public schools were hardly centres of excellence. For example, the pupils of Rugby School took their masters prisoner at sword-point and were overcome after the reading of the Riot Act resulted in an armed rescue. With very little parental supervision, many schools, even the big names, provided a shoddy education in return for their fees. At Eton, to keep the costs of teaching staff down, boys could be taught in groups that were nearly 200 strong. While conditions were not so extreme at Edinburgh, in Maxwell’s early years, classes could have 60 or more pupils.

However, reforms were underway in the school system, with more opportunity to have a ‘modern’ side as an alternative to the classics, and Edinburgh Academy was arguably more up-to-date in its approach than many of its older English equivalents. Even so, not used to the pressures of school life, having always had the time to think at his own pace, Maxwell came across as slow to learn. A combination of this and his rural accent earned him the nickname Dafty, which stuck even when it became clear that he was extremely academically gifted. Inevitably, though, so far away from his familiar home and the estate, it took Maxwell a while to bed in. A class mate called him “A locomotive under full steam, but with the wheels not gripping the track”.

Maxwell was not exactly a loner at school, but simply seemed to carry on as he had before, doing his own thing – if others wanted to join him, that was fine, but he seemed in no hurry to conform. Thankfully, his aunts quickly provided him with more conventional clothing when it was realised that his dress appeared more than a little eccentric. Maxwell certainly seemed comfortable when at home at Isabella’s house, 31 Heriot Row, a handsome four-storey grey stone townhouse with a small park out the front. He had a chance to explore both the house’s excellent library and what the natural world of Edinburgh had on offer for him to observe. Though the school took boarders, it always had day boys as well, including Maxwell.

With time, Maxwell’s limited social contact at school grew. A like-minded student who did not consider it embarrassing to be academic, Lewis Campbell moved to live near Heriot Row, and soon the two boys spent their journeys to and from school together, developing a strong bond that would last a lifetime. They had now reached an age when the school added mathematics to its limited classical curriculum – something omitted in the first two years – and Maxwell not only found that he excelled at the subject, but that he and Campbell shared a love of maths (and a certain amount of rivalry in their ability to solve mathematical problems).

Once this barrier was broken through, it seemed easier to gain friends who had an interest in science and nature, notably Peter Tait. Another lifelong friend, Tait would himself go on to become one of Scotland’s leading physics professors, in his early career even managing to beat Maxwell to take an academic post. At school, Maxwell came second to Tait in mathematics in 1846 (at the time his best subjects were scripture, biography and English verses) but pulled ahead in 1847. When secure in his little group with Tait and Campbell, Maxwell loved the opportunity to puzzle through mathematical and physical challenges, something that inspired him at the age of 14 to come up with his first academic paper – though strangely his investigations owed as much to the arts as the sciences.

The young mathematician

Maxwell’s father regularly took him to meetings of both the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Royal Scottish Society of Arts (RSSA). It was here that Maxwell became familiar with the work of the local artist David Ramsay Hay. In Hay’s philosophy, Maxwell found a point of view that was similar to his own – Hay both delighted in the beauty of nature and wanted to apply scientific measurements to it. Maxwell would later spend much effort on the nature of colour and colour vision – Hay was interested in a mathematical representation of the beauty of colour. But, equally, Hay was fascinated by the mathematics of shape and it was here that Maxwell’s paper seems to have drawn its inspiration. Hay would later give a paper at the RSSA on ‘Description of a machine for drawing a perfect egg-oval’. Maxwell’s youthful paper was on the subject of curves such as ovals that can be drawn using a pencil, a piece of string and pins.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMaxwell’s experimental apparatus resembled a primitive version of the popular 1960s toy Spirograph. By placing pins through a sheet of paper into a piece of card and looping a length of string around the pins, it’s possible with some care to draw simple geometric shapes. With a single pin, you get a circle. Two pins produce the dual foci of an egg-like ellipse. This much was standard school fare, but Maxwell took the investigation significantly further. He looked at what would happen with the string tied to one or more pins and the pencil, allowing for different numbers of loops around each of the two pins, and worked out an equation that linked the number of loops, the distance between the pins and the length of the string.

Maxwell shared his work with his father, who showed it to his friend James Forbes, Professor of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh University. Fascinated by this precocious piece of work, Forbes brought in a mathematician from the university, Philip Kelland, who checked through the literature for precedents. Although some similar work had been done by the French scientist and philosopher René Descartes, Kelland discovered that not only was Maxwell’s approach simpler and easier to understand than Descartes’, it was more general than the results that Descartes had published.

Given the originality of young Maxwell’s work, Forbes was not going to let the effort go by rewarded with nothing more than a pat on the head. He managed to present Maxwell’s paper, now grandly titled ‘Observations on Circumscribed Figures Having a Plurality of Foci, and Radii of Various Proportions’, at the Royal Society of Edinburgh in April 1846.

The 14-year-old Maxwell could not present the paper himself as he was both too young to do so and not a member, but he had regularly attended Royal Society meetings with his father and was present to hear his work read. The paper was well received and cemented Maxwell’s growing feeling that his future lay in science and mathematics.

l Professor Maxwell’s Duplicitous Demon by Brian Clegg is out now, published by Icon Books at £16.99, www.brianclegg.net