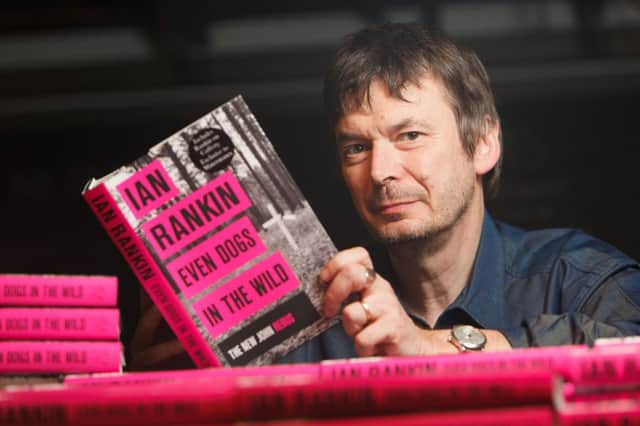

Book review: Even Dogs In The Wild by Ian Rankin

Even Dogs In The Wild by Ian Rankin | Orion, £19.99

There’s a reason why Ian Rankin sells squillions of copies. The bien pensants of the Edinburgh he so carefully, cleverly and coldly dissects may not care to admit it in mixed company, but he is not just a superior genre writer, but a very good writer indeed. This, the twenty-somethingth of the Rebus series depending on one’s bibliographical precision, is a novel as canny and subtle, as grimy and noble, as the hero he has introduced to the pantheon of sleuths. Rebus, now retired, is brought back as a “consulting detective”, a sly wee wink to Arthur Conan Doyle, to help out Siobhan Clarke and Malcolm Fox. The most notable thing about this return for Rebus is how Rankin is at his best when he is choreographing an ensemble cast. Rebus is depressive and gloomy, sarcastic and lonely. To put that in play with Clarke’s testy, upright and lonely character, triangulated with Fox as the melancholic, righteous and lonely cop who spies on other cops makes for intriguing drama, but also emotional heft. None of the characters in Rankin’s work really have friends – they have alliances, acquaintances, professional colleagues, dear apprentices and rivals they have come to respect, but they are all strangely alone. A running joke about Rebus not getting a farewell party is both precise and poignant.

That is why seeing them work together and apart is so appealing. Rebus is brought back as two investigations collide. An Edinburgh lawyer has been killed in his home. Rebus’s nemesis, Ger Cafferty, has been the recipient of a dodged bullet through the window. Both have been sent the same note vowing revenge. At the same time, a group of Glaswegian thugs have turned up, wanting a word in the ear of a former, light-fingered comrade, and to expand their operations east. It means Cafferty and Rebus have to team up – not being a police officer has some advantages – with each suspecting the other, each playing a long game and each, slightly, admiring the other.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere is a line during Malcolm Fox’s scene waiting to see his ill father: “No, it was his father’s sour realism he’d reached out for – and part of him still wanted it” – that seems to me to encapsulate the Rankin aesthetic. He depicts a world where the good are frustrated and compromised, where the villains have a code of honour and where the wicked go unpunished. One of the virtues of the crime genre is to be a thermometer to contemporary anxieties, and here Rankin deals with not just the most obvious ghastliness, in the form of “instances of historic abuse”, but the problems arising from the creation of Police Scotland. No-one is quite as good at the procedural part of “police procedural” as Rankin and there is a great deal of skill involved in making inter-departmental rivalries as gripping as he makes them.

It brings into sharp relief the difference between the police procedural and the “Golden Age” crime novels of Christie, Sayers and Marsh. There is simply – spoiler alert – no way for the reader to deduce the murderer from the set-up. Rebus doesn’t uncover the facts, he learns them. One tiny exchange catches this wonderfully: “It’s a theory,” Rebus acknowledged. “Everything is, until there’s proof.” The momentum of the novel is in the proliferation of hypotheses against the blunt and slowly revealed facts. The way in which throwaway details, from a desk drawer being ajar to restaurant flyers to a stray dog – one of these is a clever red herring – accumulate importance is done with expertise.

As with the other Rebus novels, there is a silent character almost more important than Rebus, Clarke, Fox and Cafferty: the city of Edinburgh itself. I wonder if the pleasure readers get from the Rebus books in some way depends on their familiarity with the city. At one crucial juncture, an all-night petrol station on Leith Walk is mentioned. My eyebrow immediately hit the ceiling – there are no all-night petrol stations on Leith Walk. It turns out to be an important error on the character’s rather than the author’s part, but the frisson of recognition is clearly part of the appeal.

Pacy, engaging, smart, ingenious, excellently riddled and raddled – what’s not to like about Rebus? Well, one thing does loom. Rankin has kept time with the times very neatly, and, by my count, this is the fourth Rebus novel since the self-proclaimed “last” Rebus, Exit Music. And all good things etc as the saying goes. Is there a “Reichenbach” file on Rankin’s computer, a way to deal with his own character’s inevitable mortality? He might be smoking less – and sceptical about vaping – and drinking less, but one wouldn’t want him wheeled out to grumble and mumble at his erstwhile protégés forever. Give him a great send-off, as he deserves. And as they deserve – in Fox and Clarke, Rankin has created characters equal to his most famous, and Even Dogs In The Wild at least provides them with professional and personal unfinished business.