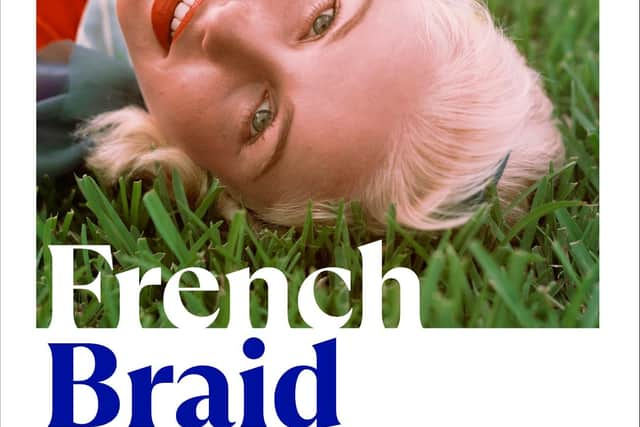

Book review: French Braid, by Anne Tyler

Near the end of this entrancing family novel comes news of another marriage. A younger member of the family is surprised that the woman, Lily, didn’t even tell her daughter she was getting married again. “Oh well,” his mother says, “this is America, remember. This country was settled by dissidents and malcontents and misfits and adventurers. Thorny people. They don’t always follow the etiquette.”

Fair enough, and nobody writes better about families than Anne Tyler. Moreover she has a gift denied many novelists of writing sympathetically about people who lead apparently humdrum lives and who would be unlikely, many of them anyway, to read much, certainly not her kind of intelligent, probing novel. Here she writes about a family in which connections between its members are strained but never quite severed.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt begins with a nice piece of misdirection, a conversation between young lovers on a train journey to Baltimore, the girl Serena’s home city. I say “misdirection” because reading this first chapter, you assume that the novel will be Serena and James’s story. But it isn’t. It’s about Serena’s family, the Garretts, and their connectionns are frayed and loose.

We go back then to 1959 and the only family vacation the Garretts, Robin and Mercy, and their children Alice, Lily and little David, ever took together. Alice was then 17 and this rather drab and unrewarding week in a lakeside cabin is mostly seen through her eyes. Robin, who owns a plumbing materials store, spends time in the lake. To his disappointment his little son, David, is frightened of the water, and will grow up sure his father didn’t like him. Mercy goes sketching in the woods. Fifteen year-old Lily takes up with an unsuitable boy and expects a proposal of marriage by the end of the week. Alice, a reflective girl, keeps house and keeps watch too over her sister and little brother. The last meal of the week is admirably done. Lily, heart-broken, though her heart will soon be repaired, keeps to her room. When Robin angrily says she will be falling for a new boy before the week is out, the following paragraph reads:

“‘She says nobody understands her and she wants to die,’ Mercy told him. Then she asked, ’Can I have the rest of your salad?’”

This, by the way, consists mostly of avocados which Robin has viewed with distrust, even suspicion, as if, perhaps, they were un-American.

Soon after the vacation Mercy will move out of the house and live and sleep in her studio, though she returns home to cook Robin’s breakfast and the new separate design for living is never openly acknowledged, even as the years pass and the children become middle-aged.

Tyler presents her characters both as they see themselves and as others see them. Bringing off this double vision is very difficult. Few have managed it better than Jane Austen, but in her case this double vision was mostly confined to her central figure or heroine. She rarely attempted to show us her male characters except as they presented themselves to the world. Tyler contrives to do this, here in the case of both Robin and David.

Advertisement

Hide AdShe has the lightest touch. This novel spans 60 years, from that Lakeside vacation when Eisenhower was in the White House and the American Dream was alive to the current pandemic. Up-to-date fictional treatments of the covid years have what the American car industry had in its prime – “built-in obsolescence” – but it is a measure of Tyler’s skill and her uncanny lightness of touch that I guess her treatment of the pandemic will seem fictional rather than journalistic/historical when people read this novel a couple of generations from now.

There will surely be such readers if there are still readers of any novels then. Tyler has that rare ability to do much with what seems little, to bring the ordinary and usually unregarded lives of ordinary people to life and make them matter.

French Braid, by Anne Tyler, Penguin, 244pp, £16.99

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions