Lori Anderson: Don’t let germs be your gift

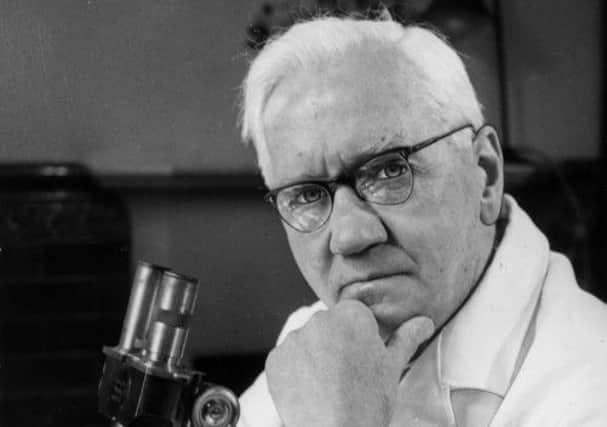

Marilyn Monroe’s breathy rendition of Happy Birthday Mr President may have strained the seams of her Jean Louis dress, but I’m feeling the same way about having to sing Happy Birthday twice while lathering up under the hot water tap. Why twice? Well, I do what I’m told and it has been proven to be an effective way to ensure that we spend enough time scrubbing our mitts clean of bugs and germs. This year anyone joining me in repeat choruses of Happy Birthday can direct them towards Mr Penicillin – it’s 80 years since this wonder drug went into commercial production and earned Alexander Fleming the Nobel Prize and a place in the history books. For the first time, mankind had a chemical weapon in the fight against the bugs, bacteria and viruses that had scythed through the population since the 14th century and the Black Death, to 1918 and the Spanish flu.

Since then we have created an arsenal of what is collectively known as “antibiotics”. Strictly speaking, antibiotics are produced naturally by microbes and many of the other drugs are artificially engineered in the lab; a more accurate term is “antimicrobials” and these can break down into anti-virals, anti-bacterial and anti-fungals, depending on their targets. Yet semantics aside, something chilling has begun to happen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBugs are fighting back. Staphylococcus Aureus, the bacteria Fleming was investigating when he found it was destroyed by penicillin, became resistant to penicillin in the 1950s, so a new drug was developed in the 1960s called methicillin. However, in the 1990s Staphylococcus Aureus became resistant to Methicillin and mutated into MRSA. There are now drug-resistant strains of bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites and the rise of air travel means people infected with resistant microbes in one country can quickly spread them to another.

The horror story I’ve been reading is published next week by Penguin Specials. The Drugs Don’t Work: A Global Threat by Professor Dame Sally C Davies, Chief Medical Officer for England, is a startling and disturbing read. She writes: “We have taken antibacterial and other antimicrobial drugs for granted for too long. We have misused them through overuse and false prescription and as a result the bugs are growing in resistance and fighting back. We are also not developing new drugs fast enough. This is not a distant threat: already, resistant bugs are killing 25,000 people a year across Europe. That is almost the same number as die in road traffic accidents.”

The prescription for tackling this problem is wide-ranging and runs from the personal to the global, from you and I, up to the UN. First we can all go back to nursery school and learn to wash our hands properly this time. A study by Michigan State University, who had the unenviable task of watching 3,700 people wash their hands in the toilets of bars, restaurants, offices and gyms, found 10 per cent didn’t even bother (shudder), 30 per cent didn’t use soap (why even bother?), while 65 per cent did scrub but not for long enough. So remember, you need to sing the bugs to death.

We also need to stop demanding antibiotics from our doctors when we have a viral infection; half of us think drugs such as penicillin are effective against colds and flus and they aren’t. In fairness, this is more applicable to our profligate European neighbours who use twice as many antibiotics as we do, for on the Continent they are available over the counter in pharmacies. (In the UK there are 17 defined daily doses of antibiotics per 1,000 people, in Greece it was 38 per 1,000). Health experts insist there needs to be a global ban on over the counter sales of antibiotics and they should no longer be used on animals for non-therapeutic reasons – a portion of the 447 tons of antibiotics sold in the UK each year for use on animals are to fatten them up prior to slaughter.

Opponents of “Big Pharma” may not like what Prof Davies also suggests is necessary: a £50 million prize for anyone who can discover and develop a new class of antimicrobial drugs. For the grim fact is that research has stalled. The last class of antibacterial drugs was found in 1987. Drug companies argue they can no longer make enough money out of antimicrobial drugs to justify the investment of up to £1 billion required to develop a new medicine. The return on investment is greater for drugs targeting cancer, diabetes and arthritis, chronic diseases that require patients take the same drug over a long period of time.

She writes: “Our response needs to be global and multifaceted, but if we do work together, bringing the ingenuity of humanity to this real, growing and often forgotten global threat, we can manage and mitigate the risk of antimicrobial resistance, which is just as important and deadly as climate change and international terrorism … If we do not address this planetary threat, then within a generation we will face an apocalyptic scenario where people will die of routine infections because we have run out of antimicrobial drugs.”

The consequence of doing nothing is grim. Prof Davies paints a picture of Britain in 2043 where it is a criminal offence to be infected and in public, where isolation sanitariums are set up where the unlucky go to die, and where once-routine operations are prohibited in case of infection.

Yet what is fascinating was the prescience of the Scot who found what we are now in danger of losing. In 1945, at his Nobel lecture, Alexander Fleming said: “The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant.”