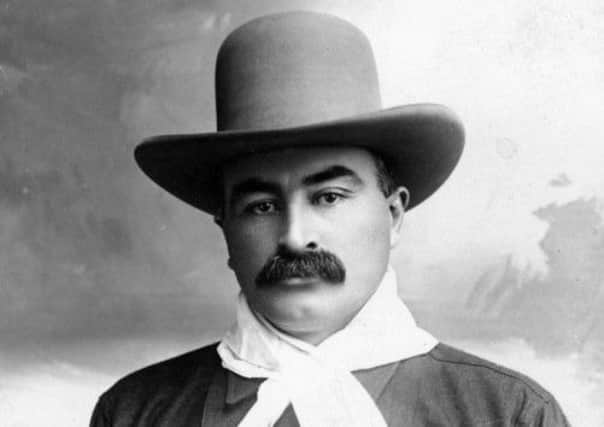

Scot who saved American buffalo subject of film

The Buffalo King tells the tale of James “Scotty” Philip, who was born in Dallas, Moray, in 1858. One of ten siblings, he emigrated to the US in 1874 aged 15 in search of adventure.

Writer and director Justin Koehler grew up near Philip, South Dakota, a town named after the Scot. “I grew up 20 minutes from that town and I had no idea who Scotty Philip was, which was kind of embarrassing. How could I come from South Dakota and not know who he was?” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He should be a South Dakota hero, if not a North American hero. But this encouraged me to tackle this story and get it out there the way it should be.”

Working as a labourer, Philip moved from Kansas to the Dakota Territory in the Midwest to look for gold in the Black Hills. When he failed to find his fortune there, Philip moved from job to job. He was a scout in the US army, a ranch hand and a cowboy.

He built up a herd of cattle and settled on a ranch on part of an Indian reservation, which he was only allowed to do as a white man because his wife Sarah was part-Native American. He went on to become a wealthy cattle farmer and a senator.

Koehler said as a schoolboy Philip had won a blindfolded race by fearlessly sprinting for the finishing line. Asked if he had been “peeking”, Philip said: “No, ma’am, I kept the wind in my face.”

“He brought the same attitude here,” Koehler said: “He didn’t care what obstacles he was going to meet, he just went ahead. He just went for it, and it was something that was instilled in him at a young age.”

While he was building his ranch, Philip became involved with the preservation of the buffalo, or American bison. The animals had once roamed the grasslands in massive herds, but a combination of hunting and the introduction of diseases from domestic cattle had driven them to the brink of extinction.

Philip met a rancher called Peter Dupree who had managed to catch five buffalo calves during the last big hunt on the Grand River in 1881. After Dupree’s death, Philip bought his herd for $10,000, the equivalent of $250,000 nowadays.

Koehler said he believed Philip was motivated by outrage at the way the US government had treated Native American tribes. As a soldier he had witnessed the massacres at Wounded Knee and Fort Robinson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKoehler said: “There are letters he sent back to Scotland in which he says how appalled he was at how the government was treating the Native Americans and what they were putting them through.

“He realised that if you eliminated the buffalo, you eliminated the Native Americans, and that was the mindset of the American government. Scotty could not understand this because he had tremendous respect for the Native Americans.”

He added: “He was just thinking differently from people of that time. In fact, I would say his thinking would be different from most people today.

“If he was alive today, he would be an icon, but he was certainly years ahead of his time.”

In 1901, Philip and his ranchers drove the herd of buffalo, now numbering 50, to a pasture set up specially for them. Through careful management, the herd expanded to almost 1,000 and became the source of stock for numerous national and state parks throughout the US.

Official figures show that the buffalo population was reduced from an estimated figure of 40 million to a low point of just 750 surviving buffalo in 1890, but by 2000 the breed had recovered to 360,000.

Philip’s funeral was attended by hundreds of mourners from all walks of life, following his sudden death aged 53 in 1911 from a cerebral haemorrhage.

Koehler said: “His funeral said it all. It was this huge event. They laid down a track just to get a train to bring out mourners, and the mourners consisted of politicians, because he was a senator; Native Americans; other cattlemen and friends. The diversity of people tells you a lot.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe documentary has already received critical acclaim on the festival circuit, winning best documentary at the South Dakota Film Festival, as well as opening several other festivals. It has been submitted to the Glasgow Film Festival for inclusion in next year’s programme.