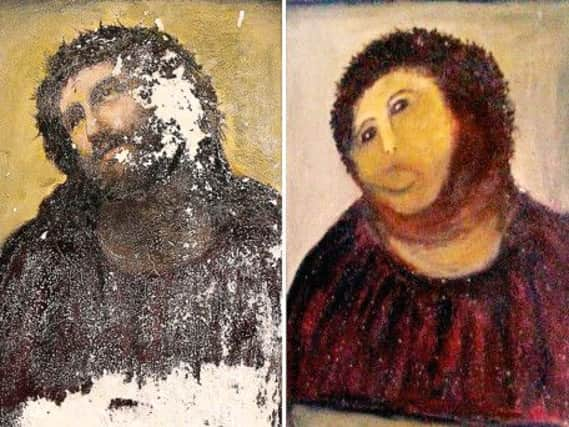

Ridiculed Jesus fresco proves blessing in diguise

News of the conscientious, if utterly failed, restoration in 2012 rocketed around the globe on Twitter and Facebook – the image likened variously to a monkey or hedgehog, and superimposed in memes and parodies on the Mona Lisa and a Campbell’s Soup tin.

But these days, people in this village of medieval palaces and winding lanes in northeast Spain are giving the artist, Cecilia Gimenez, and her work a miraculous reassessment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGrief has turned to gratitude for divine intervention – the blessing of free publicity – that has made Borja, a town of just 5,000 people, a magnet for thousands of curious tourists eager to see her handiwork.

Nearby vineyards are squabbling over the rights to splash the image on their wine labels. Her smudgy rendering is now being touted as a profound pop-art icon.

A comic opera is in the works in the United States, the story of how a woman ruined a fresco and saved a town.

“For me, it’s a story of faith,” said Andrew Flack, the opera’s librettist who travelled to Borja for research on the proposed production. “It’s a miracle how it has boosted tourism. Why are people coming to see it if it is such a terrible work of art? It’s a pilgrimage of sorts, driven by the media into a phenomenon. God works in mysterious ways. Your disaster could be my miracle.”

Since the makeover, the image has attracted more than 150,000 tourists from around the world to the 16th-century Sanctuary of Our Lady of Mercy on a mountain overlooking Borja. Visitors pay one euro to study the fresco, encased on a flaking wall behind a clear, bolted cover.

The church’s original “Ecce Homo” portrait of a mournful Jesus dated to the 1930s, when Elias Garcia Martinez, a Zaragoza art professor, painted it on the church wall.

Borja residents did not much notice the painting because the church is dominated by a gilded 18th century baroque altar. But over the years, it bothered Gimenez to see the bottom third of the fresco vanish, crumbling in the humidity of the dank church.

In her home in Borja, she recounted that she spent her summers in an apartment by the church. She said she touched up the portrait repeatedly over the years – with the knowledge of the parish priest and the caretakers, a family that has lived there for generations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut eventually, she said, it needed major work, which was abruptly halted after someone complained about the first stage of her brushwork.

The story appeared in a local newspaper, then all over the world. In the beginning, after the news broke, her relatives said she cried and refused to eat. “I felt devastated,” Gimenez said. “They said it was a crazy old woman who destroyed a portrait that was worth a lot of money.”

Today her celebrity has grown. She hands out prizes for a competition of young artists, who paint their own Ecce Homo portraits. This Christmas, the image of her Ecce Homo is stamped on the town’s local lottery tickets. The portrait also plays a bit part in a popular Spanish movie, with a couple of thieves trying to steal it.

“I can’t explain the reaction. I went to see Ecce Homo myself, and still I don’t understand it”, said Borja’s mayor Miguel Arilla.

In the economic crisis of the past six years, 300 jobs vanished, he said, but with the tourism boom, restaurants remained stable. Local museums, he added, also benefited. The nearby Museum of Colegiata, housed in a 16th-century Renaissance mansion, experienced a rise in annual visits to 70,000 from 7,000 for its religious, medieval art.

But fame has also provoked bickering.

The grandchildren of the original artist ceded any share of their rights to benefit a hospital foundation that manages the church, the mayor said.

But, he said, the great-grandchildren sent a letter through a Valencia lawyer seeking to erase the portrait entirely because the work “damages the honour of the family”.

The city already commissioned a professional study that concluded it was impossible to restore the piece.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs president of the hospital foundation, Arilla is also involved in final negotiations to sell the rights for the exact image to the Aragonesas winery in neighbouring Magallon.

The winery moved within hours after the news of the failed restoration broke to secure rights to the image, according to Fernando Cura, commercial director for the winery.