New book sheds light on Scot who tried to topple Lenin

Now, more than a century on from his failed attempts to overthrow the Bolshevik regime in revolutionary Russia, a new book has shed light on the extraordinary role played by Robert Bruce Lockhart.

The Anstruther-born former British acting consul general in Moscow is often remembered nowadays as a colourful character, notorious not just for his service, but his love of drink and women.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

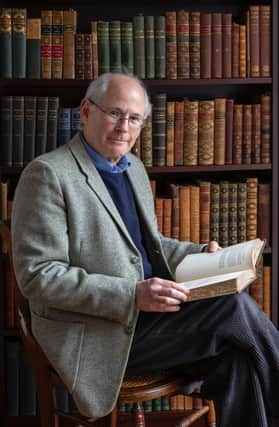

Hide AdHowever, in what is billed as the most comprehensive account yet of his time in Russia, Jonathan Schneer’s book argues that Lockhart is unfairly characterised as a “playboy dilettante” who found himself out of his depth.

Instead, ‘The Lockhart Plot’ argues that the Scot’s efforts to sow the seeds of counter revolution helped shape the tense relations between Britain and Russia which persist to this day.

Its publication is timely, given it coincides with the release of a redacted version of the Intelligence and Security Committee's long-awaited report into Russian activity in the UK.

Back in the heady days of 1918, however, it was the Brits who were looking to disrupt domestic politics in Russia, with Lockhart integral to efforts to undermine Vladimir Lenin’s government.

While the bold plot is routinely associated with Sidney Reilly, a Russian national who worked for the British security services, and later inspired Ian Fleming, Schneer, emeritus professor in British history at Georgia Tech in Atlanta, argues that it originated with Lockhart.

Its aim, he said, was the destruction of Bolshevism, a shift Lockhart hoped would bring the Russians back into World War One on the Allied side.

After the Bolsheviks seized power in late 1917, Lockhart met with David Lloyd George in Downing Street. The prime minister told him to return to Russia as Britain’s unofficial envoy, and persuade them to stay in the war against Germany.

There was, however, ambiguity surrounding Lockhart’s mission, and the extent to which it was supported. Though he had the backing of Lloyd George and Lord Milner, a key member of Britain’s wartime cabinet, many ministers were opposed to Lockhart’s goal, reasoning that in order to win the war, they could not simply hope for the Bolsheviks to play ball.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThat scepticism hardened, and by May 1918, the Foreign Office and Downing Street rejected the idea that the Bolsheviks could be won over, forcing Lockhart to change tack. He began advocating occupation of Vladivostok, Murmansk, and Archangel, whether the Russians gave permission or not

By May, the seeds of a counter-revolutionary force had taken root. Lockhart and Denis Garstin, a member of the British embassy, were sending cables to Whitehall informing them that old Tsarist army units were ready to mobilise.

It represented a significant U-turn, but Schneer believes Lockhart came to the decision after realising the Bolsheviks no longer feared the prospect of a German invasion, and that Whitehall would have it no other way.

In any case, he adds, the Scot was likely seduced by the opportunity to exercise a decisive influence in Russian and world affairs, as well as “the sheer thrill of wielding power in a chaotic situation.”

In the end, an attempted assassination attempt on Lenin by a young woman called Fanny Kaplan spurred the Cheka, Lenin’s secret police force, into action.

The plot to overthrow the Bolsheviks was thwarted after Lockhart turned to anti-Bolshevik Latvian officers, who had in fact been sent to him by Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of the Cheka.

The Scot was arrested and interrogated at the Kremlin, only to be later freed in an exchange for his Russian counterpart in London.

Schneer said that while some historians regard the Lockhart plot as a “minor matter in the great sweep of the revolutionary period,” they were mistaken.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the last fortnight of August 1918, he said, Lockhart and a handful of co-conspirators “attempted nothing less than to wrench the world onto a different path,” and one which helped - or perhaps hindered - relations between Britain and Russia over the course of the following century.

“Many things have determined the tenor of Russian and western relations, but the Lockhart plot certainly did nothing to help it, and it did everything to confirm Russian paranoia,” Schneer said.

“It fed into the suspicions and fears that the Bolsheviks had about what those in the west intended for them. It strengthened an authoritarian impulse which was there already, so I suppose there is a line which runs all the way from Felix Dzerzhinsky to Vladimir Putin.”

‘The Lockhart Plot: Love, Betrayal, Assassination and Counter-Revolution in Lenin’s Russia’ is published by Oxford University Press.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

The dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.