James Young Simpson ‘used spin’ to promote chloroform

Academics studying the life of Simpson believe that the Victorian physician was a gifted self-publicist who manufactured a ferocious row with the Church by exaggerating its moral difficulties with anaesthesia.

The research challenges previous interpretations of Simpson’s life, which have suggested there was a fearsome religious backlash to chloroform when he was pioneering the use of the chemical compound.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe paper by Dr Neil MacGillivray and Professor Ewen Cameron has unearthed correspondence by Simpson, which sheds light on the strategy he adopted to bring the use of anaesthetics into mainstream medicine.

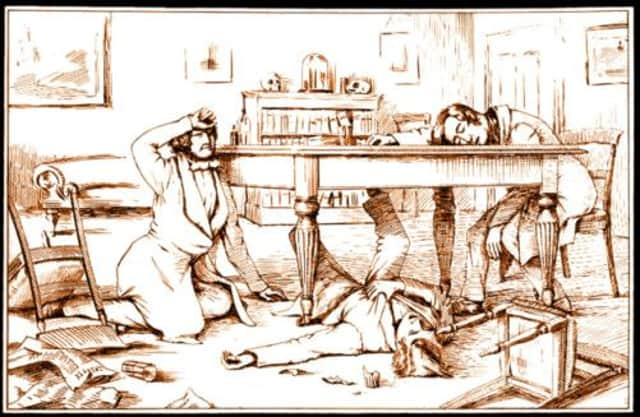

When Simpson introduced the use of chloroform as an anaesthetic in Edinburgh in the 1840s, many believed that Calvinistic Scotland would object to the technique on religious grounds. It was thought that objectors would take the view that relieving the pain of childbirth was contrary to the evangelical belief that human sins could be atoned through suffering.

In order to combat this argument, the paper, Sir James Young Simpson and religion: myths and controversies, points out that the physician produced long, detailed theological documents in defence of chloroform.

According to the authors, the anticipated religious uprising failed to materialise and it was Simpson’s pamphlets that encouraged the myth of a widespread opposition to medical progress.

“Previous papers have said that the Scottish Calvinists put the boot into Simpson, but this is complete nonsense,” MacGillivray told Scotland on Sunday. “There may have been one or two clergymen who complained about it. But Simpson took the view that any publicity was good publicity.”

Simpson’s articles made their way from Edinburgh to London, where he was desperate to have his techniques introduced. MacGillivray argued that Simpson’s elaborate reaction to potential opposition had the effect of “deliberately” exaggerating the religious opposition because the doctor believed “the publicity could only be valuable”.

MacGillivray backed up his argument with a letter written by Simpson, which has been unearthed in the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. The letter, written to a London colleague Dr Protheroe Smith, acknowledges that religious opposition had largely evaporated in Edinburgh.

An extract of Simpson’s letter reads: “All religious objection to chloroform has entirely ceased among us; except an occasional remark from some caustic old maid whose prospects of using chloroform are forever passed, or a sneer from some antiquated lady.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen a version of the correspondence between the two doctors was published, MacGillivray’s article notes that the paragraph above was omitted. Around the same time in a separate correspondence with another London physician, Dr Forbes, dated 1847, Simpson wrote a letter that appears to contradict his privately held view that the objections had pretty much disappeared.

The letter to Dr Forbes talked about “hideous prejudices, long prayers and sermons against it [chloroform]”.

Yesterday, MacGillivrary argued that the discrepancy between the two views offered by Simpson supported his view that the doctor exaggerated the strength of the religious objections.

MacGillivray said: “On the one hand, he is saying that there were only caustic old maids and the next thing he is saying there were long prayers and sermons. You can’t have it both ways.

“He was an incredibly able man – and like many able men he was not adverse to promoting himself. This publicity encouraged the myth of Scottish religious objections, but did not delay the widespread use of chloroform, so Simpson’s name was brought to international prominence.

“In the case of so many great men, they become great men because they advance themselves and take every single opportunity to do so.”

But MacGillivary’s interpretation was disputed by Dr Morrice McCrae, author of the biography Simpson, The Turbulent Life Of A Medical Pioneer.

He agreed that Simpson had a knack for self-promotion, but took issue with the idea that this talent extended to deliberate exaggeration of the religious opposition that he faced.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I don’t think that’s what happened,” McCrae said. “Everyone, including Simpson himself, was sure that there would be enormous opposition. That’s why he wrote the pamphlet.

“But there wasn’t really any opposition. The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Moderator of the Church of Scotland accepted what Simpson said. He was simply preparing for what he believed would be tremendous onslaught.”